Revolver

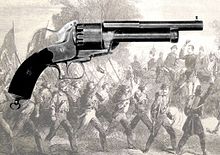

Several approaches to the problem of increasing the rate of fire were developed, the earliest involving multi-barrelled weapons which allowed two or more shots without reloading.

[7] During the late 16th century in China, Zhao Shi-zhen invented the Xun Lei Chong, a five-barreled musket revolver spear.

'[16] The weapon was not adopted, however, for the same reason that previous similar guns had not been widely distributed: they were complicated, difficult to use and prohibitively expensive to make.

Originally they were muzzleloaders, but in 1837, the Belgian gunsmith Mariette invented a hammerless pepperbox with a ring trigger and turn-off barrels that could be unscrewed.

[20] Nevertheless, the new mechanism, coupled with Colt's ability as a salesman - one historian describing him as a 'a pioneer Madison Avenue-style pitchman'[21] - and his approach to manufacturing ensured his influence spread.

The build quality of his company's guns became famous, and its armories in America and England trained several seminal generations of toolmakers and other machinists, who had great influence in other manufacturing efforts of the next half century.

[24] On November 17, 1856, Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson signed an agreement for the exclusive use of the Rollin White Patent at a rate of 25 cents for every revolver.

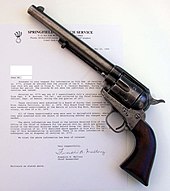

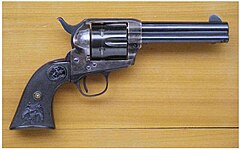

[28] This popular design, which was a culmination of many of the advances introduced in earlier weapons, fired 6 metallic cartridges and was offered in over 30 different calibers and various barrel lengths.

Although originally made for the United States Army, the Model 1873 was widely distributed and popular with civilians, ranchers, lawmen, and outlaws alike.

Top-break actions had the ability to eject all empty shells simultaneously and exposed all chambers for easy reloading, but having the frame hinged into two halves weakened the gun and negatively affected accuracy due to the lack of rigidity.

[29] Revolvers have remained popular in many areas, although for law enforcement and military personnel, they have largely been supplanted by magazine-fed semi-automatic pistols, such as the Beretta M9 and the SIG Sauer M17, especially in circumstances where faster reload times and higher cartridge capacity are important.

[30] In 1815, (sometimes incorrectly dated as 1825) a French inventor called Julien Leroy patented a flintlock and percussion revolving rifle with a mechanically indexed cylinder and a priming magazine.

[31][32] Elisha Collier of Boston, Massachusetts, patented a flintlock revolver in Britain in 1818, and significant numbers were being produced in London by 1822.

[33] The origination of this invention is in doubt, as similar designs were patented in the same year by Artemus Wheeler in the United States, and by Cornelius Coolidge in France.[34].

In 1856, Horace Smith & Daniel Wesson formed a partnership (S&W), then developed and manufactured a revolver chambered for a self-contained metallic cartridge.

[39] In 1993, U.S. patent 5,333,531 was issued to Roger C. Field for an economical device for minimizing the flash gap of a revolver between the barrel and the cylinder.

In contrast, other repeating firearms, such as bolt-action, lever-action, pump-action, and semi-automatic, have a single firing chamber and a mechanism to load and extract cartridges into it.

The new design incorporates polymer technology that lowers weight significantly, helps absorb recoil, and is strong enough to handle .38 Special +P and .357 Magnum loads.

Polymer technology is considered one of the major advancements in revolver history because the frame was previously always metal alloy and mostly a one-piece design.

[23] After each shot, a user was advised to raise the revolver vertically while cocking back the hammer so as to allow the fragments of the spent percussion cap to fall out safely.

In most top-break revolvers, this act also operates an extractor that pushes the cartridges in the chambers back far enough that they will fall free, or can be removed easily.

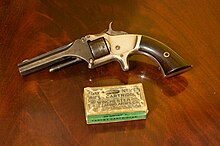

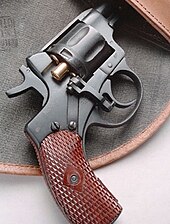

[58] The tip-up revolver was the first design to be used with metallic cartridges in the Smith & Wesson Model 1, on which the barrel pivoted upwards, hinged on the forward end of the topstrap.

Because only a single action is performed and trigger pull is lightened, firing a revolver in this way allows most shooters to achieve greater accuracy.

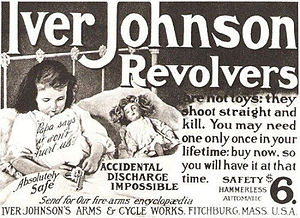

However, this will require a longer and harder trigger stroke, though this drawback can also be viewed as a safety feature, as the gun is safer against accidental discharges from being dropped.

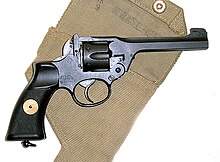

[40] The sole mode of operation was seen as reducing training time for the British Army in WWII where the revolver usage was rapid fire at very close ranges.

These are generally intended for concealed carrying, as a hammer spur could snag when the revolver is drawn from clothing, but this design may result in reduction in accuracy in aimed fire.

Double-action is preferred in high-stress situations because it allows a mode of carry in which one only has to draw and pull the trigger—no safety catch release nor separate cocking stroke is required.

[68] There is a modern revolver of Russian design, the OTs-38,[69] which uses ammunition that incorporates the silencing mechanism into the cartridge case, making the gap between cylinder and barrel irrelevant as far as the suppression issue is concerned.

The OTs-38 does need an unusually close and precise fit between the cylinder and barrel due to the shape of bullet in the special ammunition (Soviet SP-4), which was originally designed for use in a semi-automatic.

A rare class of revolvers, called automatic for its firing design, attempts to overcome this restriction, giving the high speed of a double-action with the trigger effort of a single-action.