Horseshoe bat

The most recent common ancestor of all horseshoe bats lived 34–40 million years ago, though it is unclear where the geographic roots of the family are, and attempts to determine its biogeography have been indecisive.

Horseshoe bats are relevant to humans in some regions as a source of disease, as food, and for traditional medicine.

In 1825, British zoologist John Edward Gray subdivided Vespertilionidae into subfamilies, including what he called Rhinolophina.

[3] English zoologist Thomas Bell is credited as the first to recognize horseshoe bats as a separate family, using Rhinolophidae in 1836.

In 1876, Irish zoologist George Edward Dobson returned all Asiatic horseshoe bats to Rhinolophus, additionally proposing the subfamilies Phyllorhininae (for the hipposiderids) and Rhinolophinae.

American zoologist Gerrit Smith Miller Jr. further divided the hipposiderids from the horseshoe bats in 1907, recognizing Hipposideridae as a distinct family.

[2]: xii Some authors have considered Hipposideros and associated genera as part of Rhinolophidae as recently as the early 2000s,[9] though they are now most often recognized as a separate family.

He recognized six species groups: R. simplex (now R. megaphyllus), R. lepidus, R. midas (now R. hipposideros), R. philippinensis, R. macrotis, and R. arcuatus.

[2][12] Various subgenera have been proposed as well, with six listed by Csorba et al. in 2003: Aquias, Phyllorhina, Rhinolophus, Indorhinolophus, Coelophyllus, and Rhinophyllotis.

[9] The most recent common ancestor of Rhinolophus lived an estimated 34–40 million years ago,[13] splitting from the hipposiderid lineage during the Eocene.

[13] A 2016 study using mitochondrial and nuclear DNA placed the horseshoe bats within the Yinpterochiroptera as sister to Hipposideridae.

Rhinolophus may be undersampled in the Afrotropical realm, with one genetic study estimating that there could be up to twelve cryptic species in the region.

Fur color is highly variable among species, ranging from blackish to reddish brown to bright orange-red.

Only a few other bat families have pubic nipples, including Hipposideridae, Craseonycteridae, Megadermatidae, and Rhinopomatidae; they serve as attachment points for their offspring.

[21] This is atypical among bat families, as most newborns have at least some milk teeth at birth, which are quickly replaced by the permanent set.

These echolocation characteristics are typical of bats that search for moving prey items in cluttered environments full of foliage.

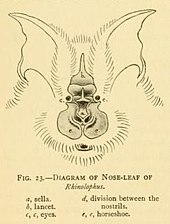

[26] Their highly furrowed nose-leafs likely assist in focusing the emission of sound, reducing the effect of environmental clutter.

[25] The nose-leaf in general acts like a parabolic reflector, aiming the produced sound while simultaneously shielding the ear from some of it.

[10] Horseshoe bats have sophisticated senses of hearing due to their well-developed cochlea,[10] and are able to detect Doppler-shifted echoes.

[10] Horseshoe bats are insectivorous, though consume other arthropods such as spiders,[18] and employ two main foraging strategies.

At least one species, the greater horseshoe bat, has been documented catching prey in the tip of its wing by bending the phalanges around it, then transferring it to its mouth.

These factors give them increased agility, and they are capable of making quick, tight turns at slow speeds.

At least one species, the greater horseshoe bat, appears to have a polygynous mating system where males attempt to establish and defend territories, attracting multiple females.

[2]: xi Other species like Lander's horseshoe bat have embryonic diapause, meaning that while fertilization occurs directly following copulation, the zygote does not implant into the uterine wall for an extended period of time.

[35] Horseshoe bat predators include birds in the order Accipitriformes (hawks, eagles, and kites), as well as falcons and owls.

[43] They are also affected by a variety of internal parasites (endoparasites), including trematodes of the genera Lecithodendrium, Plagiorchis, Prosthodendrium,[44] and cestodes of the genus Potorolepsis.

Following the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak, several animal species were examined as possible natural reservoirs of the causative coronavirus, SARS-CoV.

Though horseshoe bats appeared to be the natural reservoir of SARS-related coronaviruses, humans likely became sick through contact with infected masked palm civets, which were identified as intermediate hosts of the virus.

[53] The rufous horseshoe bat (R. rouxii) has tested seropositive for Kyasanur Forest disease, which is a tick-borne viral hemorrhagic fever known from southern India.

[56] The Ao Naga people of Northeast India are reported to use the flesh of horseshoe bats to treat asthma.