Rhythmic mode

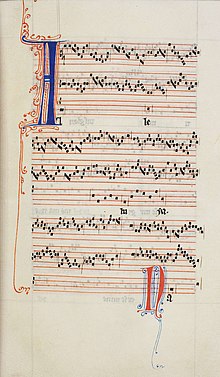

In medieval music, the rhythmic modes were set patterns of long and short durations (or rhythms).

[4] The fourth mode is rarely encountered, an exception being the second clausula of Lux magna in MS Wolfenbüttel 677, fol.

Linked notes in groups of:[10] The reading and performance of the music notated using the rhythmic modes was thus based on context.

Some medieval writers explained this as veneration for the perfection of the Holy Trinity, but it appears that this was an explanation made after the event, rather than a cause.

[14] The plica was adopted from the liquescent neumes (cephalicus) of chant notation, and receives its name (Latin for "fold") from its form which, when written as a separate note, had the shape of a U or an inverted U.

In modal notation, however, the plica usually occurs as a vertical stroke added to the end of a ligature, making it a ligatura plicata.

If the two main notes are a second apart, or at an interval of a fourth or larger, musical context must decide the pitch of the plica tone.

Anonymous IV called these currentes (Latin "running"), probably in reference to the similar figures found in pre-modal Aquitanian and Parisian polyphony.

[18] Other writers who covered the topic of rhythmic modes include Anonymous IV, who mentions the names of the composers Léonin and Pérotin as well as some of their major works, and Franco of Cologne, writing around 1260, who recognized the limitations of the system and whose name became attached to the idea of representing the duration of a note by particular notational shapes, though in fact the idea had been known and used for some time before Franco.