Ricercar

The term is also used to designate an etude or study that explores a technical device in playing an instrument, or singing.

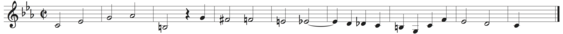

In its most common contemporary usage, it refers to an early kind of fugue, particularly one of a serious character in which the subject uses long note values.

Among the best-known ricercars are the two for harpsichord contained in Bach's The Musical Offering and Domenico Gabrielli's set of seven for solo cello.

Terminology was flexible, even lax then: whether a composer called an instrumental piece a toccata, a canzona, a fantasia, or a ricercar was clearly not a matter of strict taxonomy but a rather arbitrary decision.

Yet ricercars fall into two general types: a predominantly homophonic piece, with occasional runs and passagework, not unlike a toccata, found from the late fifteenth to the mid-sixteenth century, after which time this type of piece came to be called a toccata;[2] and from the second half of the sixteenth century onward, a sectional work in which each section begins imitatively, usually in a variation form.