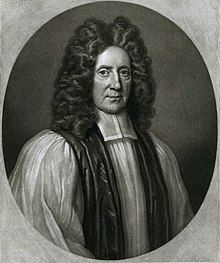

Richard Cumberland (philosopher)

In 1672, he published his major work, De legibus naturae (On natural laws), propounding utilitarianism and opposing the egoistic ethics of Thomas Hobbes.

He was educated in St Paul's School, where Samuel Pepys was a friend, and from 1649 at Magdalene College, Cambridge, where he obtained a fellowship.

Among his contemporaries and intimate friends were Hezekiah Burton, Sir Samuel Morland, who was distinguished as a mathematician, and Orlando Bridgeman, who became Lord Keeper of the Great Seal.

Cumberland's first preferment, bestowed upon him in 1658 by Sir John Norwich of the Rump Parliament, was the rectory of Brampton Ash in Northamptonshire.

The work is heavy in style, and its philosophical analysis lacks thoroughness; but its insistence on the social nature of man, and its doctrine of the common good as the supreme law of morality, anticipate the direction taken by much of the ethical thought of the following century.

A German translation by Johan Philip Cassel appeared under the title of Cumberlands phonizische Historie des Sanchoniathons (Magdeburg, 1755).

The persuasion of his friends, particularly Sir Orlando Bridgeman, at length overcame his repugnance; and to that see, though very moderately endowed, he for ever after devoted himself, and resisted every offer of translation, though repeatedly made and earnestly recommended.

When David Wilkins published the New Testament in Coptic (Novum Testamentum Aegyptium, vulgo Copticum, 1716) he presented a copy to the bishop, who began to study the language at the age of eighty-three.

"At this age," says his chaplain, "he mastered the language, and went through great part of this version, and would often give me excellent hints and remarks, as he proceeded in reading of it."

Its main design is to combat the principles which Hobbes had promulgated as to the constitution of man, the nature of morality, and the origin of society, and to prove that self-advantage is not the chief end of man, that force is not the source of personal obligation to moral conduct nor the foundation of social rights, and that the state of nature is not a state of war.

According to Parkin (p. 141) The De legibus naturae is a book about how individuals can discover the precepts of natural law and the divine obligation which lies behind it.

For writers who accepted a voluntarist and nominalist understanding of the relationship between God and man (both Cumberland and Hobbes), this was not an easy question to answer.Darwall (p. 106) writes that Cumberland follows Hobbes in attempting to provide a fully naturalistic account of the normative force of obligation and of the idea of a rational dictate, although he rejects Hobbes's theory that these derive entirely from instrumental rationality.Laws of nature are defined by him as immutably true propositions regulative of voluntary actions as to the choice of good and the avoidance of evil, and which carry with them an obligation to outward acts of obedience, even apart from civil laws and from any considerations of compacts constituting government.This definition, he says, will be admitted by all parties.

He expressly denied, however, that "they carry with them an obligation to outward acts of obedience, even apart from civil laws and from any consideration of compacts constituting governments."

They had sought to prove that there were universal truths, entitled to be called laws of nature, from the concurrence of the testimonies of many men, peoples and ages, and through generalizing the operations of certain active principles.

Cumberland admits this method to be valid, but he prefers the other, that from causes to effects, as showing more convincingly that the laws of nature carry with them a divine obligation.

In the prosecution of this method he expressly declines to have recourse to what he calls "the short and easy expedient of the Platonists," the assumption of innate ideas of the laws of nature.

He cannot assume, he says, that such ideas existed from eternity in the divine mind, but must start from the data of sense and experience, and thence by search into the nature of things to discover their laws.

Cumberland never appealed to the evidence of history, although he believed that the law of universal benevolence had been accepted by all nations and generations; and he abstains from arguments founded on revelation, feeling that it was indispensable to establish the principles of moral right on nature as a basis.

He argues that all that we see in nature is framed so as to avoid and reject what is dangerous to the integrity of its constitution; that the human race would be an anomaly in the world had it not for end its conservation in its best estate; that benevolence of all to all is what in a rational view of the creation is alone accordant with its general plan; that various peculiarities of man's body indicate that he has been made to co-operate with his fellow men and to maintain society; and that certain faculties of his mind show the common good to be more essentially connected with his perfection than any pursuit of private advantage.

Cumberland's views on this point were long abandoned by utilitarians as destroying the homogeneity and self-consistency of their theory; but John Stuart Mill and some other writers have reproduced them as necessary to its defence against charges not less serious than even inconsistency.

The answer which Cumberland gives to the question, "Whence comes our obligation to observe the laws of nature?," is that happiness flows from obedience, and misery from disobedience to them, not as the mere results of a blind necessity, but as the expressions of the divine will.

It is no peculiar faculty or distinctive function of mind; it involves no original element of cognition; it begins with sense and experience; it is gradually generated and wholly derivative.