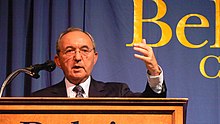

Richard Goldstone

He is considered to be one of several liberal judges who issued key rulings that undermined apartheid from within the system by tempering the worst effects of the country's racial laws.

Goldstone's work investigating violence led directly to his being nominated to serve as the first chief prosecutor of the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and for Rwanda from August 1994 to September 1996.

[2] He prosecuted a number of key war crimes suspects, notably the Bosnian Serb political and military leaders, Radovan Karadžić and Ratko Mladić.

[8] He was educated at the King Edward VII School in Johannesburg and read law at the University of the Witwatersrand, graduating in 1962 with a BA LLB cum laude.

[6] Goldstone later said that his nomination to the bench created a "moral dilemma", insofar as South African judges were expected to uphold apartheid legislation, but that, "the approach was that it was better to fight from inside than not at all".

According to Davis & Le Roux (2009), a group of liberal judges that included Goldstone, Gerald Friedman, Ray Leon, Johann Kriegler, John Milne and Lourens Ackermann sought to read the apartheid legislation "as narrowly as possible to give effect to the values of the common law".

[25] Geoffrey Budlender, former director of the anti-apartheid Legal Resources Centre, commented of Goldstone's decision in the Govender case that "it was an alert judge trying to apply human rights standards to a repressive piece of legislation.

At the time, South Africa was plagued by regular massacres as members of the African National Congress (ANC) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) fought for dominance.

The negotiations broke down soon after they started due to a mass shooting at Sebokeng township near Johannesburg in March 1990, in which 281 demonstrators were shot and 11 killed by South African police.

[39] To aid the transition to multiracial democracy, the South African government established a Commission of Inquiry Regarding the Prevention of Public Violence and Intimidation in October 1991 to investigate human rights abuses committed by the country's various political factions.

[39] One of Goldstone's most important findings was the revelation in November 1992 that a secret military intelligence unit of the South African Defence Force was working to sabotage the ANC while posing as a legitimate business corporation.

[1] Nonetheless, his impartiality and willingness to speak out led to him becoming, as the Christian Science Monitor put it in 1993, "arguably the most indispensable arbitrator in South Africa's turbulent transition to democracy."

Its chairman, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, commented that Goldstone had made an "indispensable" contribution to the peaceful democratic transition in South Africa.

[36] The commission's final report was strongly critical of the apartheid-era legal system but commended the role of a few judges, including Goldstone, who "exercised their judicial discretion in favour of justice and liberty wherever proper and possible".

It noted that although they were few in number, such figures were "influential enough to be part of the reason why the ideal of a constitutional democracy as the favoured form of government for a future South Africa continued to burn brightly throughout the darkness of the apartheid era."

"[43] Reinhard Zimmermann commented in 1995 that "Goldstone's reputation as a sound and impeccably impartial lawyer coupled with his genuine concern for social justice have invested him, across the political spectrum, with a degree of legitimacy that is probably unequalled in South Africa today.

[6] Justice Albie Sachs described Goldstone as representing "a sense of continuity" between the traditions of the past that managed to survive the years of apartheid, and the whole new era of the constitution that governs South Africa today.

[36] Notable judgments written by Goldstone included three important decisions on unfair discrimination and the right to equality: President v Hugo, Harksen v Lane, and J v Director-General, Home Affairs.

Mandela struck a deal with the UN Secretary-General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali, that Goldstone would serve only half of his four-year term as prosecutor and would then return to take up his post in South Africa.

[20] The tribunal lacked political legitimacy, financial support and prosecutorial direction; its failure to even bring any prosecutions had led to it being criticised by the media as "a fig leaf for inaction", and Goldstone was asked by the former British prime minister Edward Heath: "Why did you accept such a ridiculous job?

He was bitterly critical of what he called the "highly inappropriate and pusillanimous policy" of Western countries in declining to pursue suspected war criminals, singling out France and the United Kingdom as particular culprits.

Some commentators had advocated including an amnesty as the price for peace; Goldstone was resolutely opposed to this, not only because it would enable those responsible for atrocities to escape justice but also because of the dangerous precedent it could set, where powerful actors such as the United States could bargain away the ICTY's mandate for political convenience.

In response, Goldstone pushed through a new indictment of the Bosnian Serb president Radovan Karadžić and his army chief Ratko Mladić for the Srebrenica massacre, which was issued two weeks into the peace talks at Dayton.

[50] He lobbied President Bill Clinton to resist any such demands and made it clear that an amnesty would not be a legal basis for the ICTY to suspend indictments.

The chief US negotiator, Richard Holbrooke, described the tribunal as "a huge valuable tool" which had enabled Karadžić and Mladić to be excluded from the talks, with the Serbian side represented instead by the more conciliatory Milosević.

The Dayton Agreement put direct responsibility on all sides to send suspects to The Hague, committing the Serbian, Bosnian and Croatian governments to cooperating with the ICTY in future.

[2] In April 2004, he was appointed by Kofi Annan, the UN Secretary General, to the Independent Inquiry Committee, chaired by Paul Volcker, to investigate the Iraq Oil for Food program.

[62] The Israeli government refused to cooperate with the investigation, accusing the UN Human Rights Council of anti-Israel bias and arguing that the report could not possibly be fair.

Hamas and other armed Palestinian groups were found to have deliberately targeted Israeli civilians and sought to spread terror in southern Israel by mounting indiscriminate rocket attacks.

Goldstone said he had hoped that the commission's inquiry "would begin a new era of evenhandedness at the U.N. Human Rights Council, whose history of bias against Israel cannot be doubted".