Richard Mohun

[2][3] Mohun's family had a long association with Africa - his grandfather, William McKenny, had been a prominent figure during the colonisation of the continent and built up a comprehensive collection of photographs during his time there.

[1][4] Mohun developed an interest in the slave trade, which continued under Arab control in Eastern and Southern Africa, and became the fourth member of his family to campaign for its eradication.

[2] Mohun's sister, Lee intended to train as a nun to join a Catholic mission in the Congo, where the slavers were active, and was only dissuaded by her family who asked her to minister to African-Americans in Washington instead.

[3][6][7] His grandmother, religious writer Anna Hanson Dorsey, arranged for him to meet her acquaintance, Monsignor Denis J. O'Connell, at the Pontifical North American College in Rome in 1885.

[3][6][7] Mohun and his brother, Louis, were involved in the short-lived Nicaragua Canal Construction Company, a private American enterprise seeking link the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

[10][11] Richard secured a position as an auditor with the company's transportation division by 1891 but the project was hit by tropical disease and the Mohuns returned home to Washington by January 1892.

Eat wholesome food with very little fat to it, accompanied by a glass of good Bordeaux or Vino Tinto ... Keep regular hours; take quinine and iron when you feel run down; do not allow yourself to become constipated ...

[13][14] Dorsey was able to use this influence to arrange the appointment of Mohun as US commercial agent to the Congo Free State on 22 January 1892, filling a vacancy caused by the death-in-post of US Navy Lieutenant Emory Taunt the previous year.

The three travelled in Europe for 2–3 months before Mohun reported to Brussels to meet with King Leopold II who, in spite of his callous reputation, impressed him with his apparent ambition to bring peace and western civilization to the Congo.

[18][19] In July 1892 he assisted US citizen Warren C. Unckless in establishing a rubber factory on the Sankuru River near Lusambo for the Société anonyme belge pour le commerce du Haut-Congo.

Unckless, a plantation manager in Costa Rica, had imported experienced rubber cutters from South America to begin the enterprise but came under attack from tribesmen and a Belgian force had to be dispatched to provide security.

[20] Mohun spent much of his time in exploration of the country's interior, visiting several areas where no white man had ever ventured and making a survey of the quality of the agricultural land and the crops grown by the native population.

[22] Another time, seeking to view the native method of making cloth, he visited a remote town accompanied by only six followers covertly armed with revolvers.

[24] Mohun's diary contains little in the way of self-criticism and he reflects upon his responsibility for this incident by stating that he was "satisfied in my own conscience that I had rid the country of a brute and unnecessary member of society.

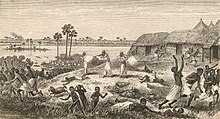

[1] Francis, Baron Dhanis, vice-governor general to the Free State, had been leading an expedition against slavers - who were led by Sefu, the son of Tippu Tip - since July 1892.

[1] Mohun had risen to the position owing to the illness of the original Chief of Artillery, a Belgian Army officer, and joined the expedition via the steamer Bruxelles sometime after it had started off from Basoko.

[22] Still in Kasongo by February Mohun had intended to take a force of some sixty soldiers, 100 porters and 90 others to Tanganyika where he planned to catch a steamer to South Africa to arrange passage to the Congolese coast.

[32] Instead Mohun, recognised for the leading role he played in many of the engagements, was in March 1894 appointed by Dhanis to be second-in-command of an expedition to determine whether there was a navigable watercourse between Lake Tanganyika and the upper Lualaba River.

[46] Mohun had remained US commercial agent throughout this time, and insisted on drawing no pay from the Belgian government for his services, though he did receive $5000 from the Société Anonyme Belge pour le commerce du Haut-Congo.

[58] On 6 July 1897 he informed his superiors of an outbreak of smallpox on the island among the Indian and native population and that an English missionary had been attacked for carrying a victim around in his arms.

[2][58] Mohun was contacted by the Belgian government, which had been impressed by his work on behalf of the United States, and was appointed a district commissioner (1st class) in their colonial service in June 1898.

[63] The overhead telegraph may have been intended as a link in the proposed line from the Cape to Cairo, it was to be supported by 7m-high poles at 150m spacings and had been allocated a budget of three million francs.

[63][64] Mohun was allowed free rein to choose his own staff and set out with five electricians/engineers (including some from Britain and France), Dr. Raan Horace Castellote as medical officer and a military escort commanded by Belgian Captain Verhellen.

[69] The expedition then proceeded to the settlement of Fort Johnston at the southern tip of Lake Nyasa where they replenished their food stocks with fish from the Shire River.

[74] In December 1900 Mohun's family contacted the US ambassador to Belgium, Lawrence Townsend, to ask him to investigate rumours of his death which had been announced at a lecture in Washington.

[78] He is regarded as one of three Americans who played key roles in opening the Belgian Congo to outsiders, alongside Stanley and the missionary William Henry Sheppard.

[8][81] Not wishing to embark upon another long appointment in Africa, Mohun wrote a request for employment to former US State Department official Thomas W. Cridler, commissioner for the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition.

Mohun was unsuccessful and never received a formal position with the exposition, though his suggestion might have led to the inclusion of the pygmy Ota Benga and other African tribesmen as part of the exhibition.

[85] Mohun was selected, in May 1907, by Thomas Fortune Ryan and Daniel Guggenheim, founders of the Forminière company to undertake a prospecting operation on the Uele River in the Kasai and Maniema regions.

[3][6][89] This was in two parts, a scientific expedition led by SP Verner for the American Congo Company that sought to trial the "Mexican Process" of utilising acetone for rubber extraction in the Congo, and a mineral prospecting party, the Mohun-Ball Expedition (also known as the Mission de Recherches Minières), with mineralogist Sydney Hobart Ball and mining engineer Alfred Chester Beatty, that sought out new gold, copper and coal deposits.