Richard Simon (priest)

His early education took place at the Oratorian college there, and a benefice enabled him to study theology at Paris, where he showed an interest in Hebrew and other Oriental languages.

Simon's approach earned him the later recognition as a "Father of the higher criticism", though this title is also given to German writers of the following century, as well as to Spinoza himself.

François Verjus was a fellow Oratorian and friend who was acting against the Benedictines of Fécamp Abbey on behalf of their commendatory abbot, the Prince de Neubourg.

[5] Simon composed a strongly worded memorandum, and the monks complained to the Abbé Abel-Louis de Sainte-Marthe, Provost General of the Oratory from 1672.

[6] The charge of Jesuitism was also brought against Simon, on the grounds that his friend's brother, Father Antoine Verjus, was a prominent member of the Society of Jesus.

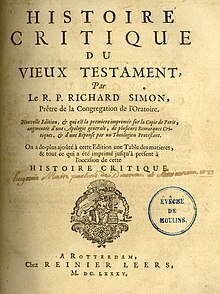

[citation needed] At the time of the printing of Simon's Histoire critique du Vieux Testament,[7] the work passed the censorship of the University of Paris, and the Chancellor of the Oratory gave his imprimatur.

The influence of Jacques-Benigne Bossuet, at that time tutor to the Dauphin of France, was invoked; the chancellor, Michael le Tellier, lent his assistance.

It presents Simon's theory of the existence during early Jewish history of recorders or annalists of the events of each period, whose writings were preserved in the public archives.

To counteract this, Simon announced his intention of publishing an annotated edition of the Prolegomena, and added to the Histoire critique a translation of the last four chapters of that work, not part of his original plan.

A faulty edition of the Histoire critique had previously been published at Amsterdam by Daniel Elzevir, based on a manuscript transcription of one of the copies of the original work which had been sent to England; and from which a Latin translation (Historia critica Veteris Testamenti, 1681, by Noël Aubert de Versé)[11] and an English translation (Critical History of the Old Testament, London, 1682)[12] were made.

It was substantially based on the Latin Vulgate, but was annotated in such a way as to cast doubt on traditional readings that were backed by Church authority.

Antoine Arnauld had compiled with others a work Perpétuité de la foi (On the Perpetuity of the Faith), the first volume of which dealt with the Eucharist.

[22] The Histoire critique du Vieux Testament encountered strong opposition from Catholics who disliked Simon's diminishing of the authority of the Church Fathers.

Isaac Newton took an interest in Simon's New Testament criticism in the early 1690s, pointed out to him by John Locke, adding from it to an Arian summary of his views that was intended for publication by Le Clerc, but remained in manuscript.

A ... celebrated man was Richard Simon ... whose 'Critical History of the Old Testament' was prohibited in 1682 at the instance of Bossuet, and by that illustrious prelate described as 'a mass of impieties and a rampart of free-thinking (libertinage).'