Riemannian manifold

The techniques of differential and integral calculus are used to pull geometric data out of the Riemannian metric.

For example, integration leads to the Riemannian distance function, whereas differentiation is used to define curvature and parallel transport.

Although John Nash proved that every Riemannian manifold arises as a submanifold of Euclidean space, and although some Riemannian manifolds are naturally exhibited or defined in that way, the idea of a Riemannian manifold emphasizes the intrinsic point of view, which defines geometric notions directly on the abstract space itself without referencing an ambient space.

Applications include physics (especially general relativity and gauge theory), computer graphics, machine learning, and cartography.

In this language, the Theorema Egregium says that the Gaussian curvature is an intrinsic property of surfaces.

In fact, the more primitive concept of a smooth manifold was first explicitly defined only in 1913 in a book by Hermann Weyl.

Specifically, the Einstein field equations are constraints on the curvature of spacetime, which is a 4-dimensional pseudo-Riemannian manifold.

does not come equipped with an inner product, a measuring stick that gives tangent vectors a concept of length and angle.

That is, the entire structure of a smooth Riemannian manifold can be encoded by a diffeomorphism to a certain embedded submanifold of some Euclidean space.

By selecting this open set to be contained in a coordinate chart, one can reduce the claim to the well-known fact that, in Euclidean geometry, the shortest curve between two points is a line.

Although the length of a curve is given by an explicit formula, it is generally impossible to write out the distance function

is non-differentiable, and it can be remarkably difficult to even determine the location or nature of these points, even in seemingly simple cases such as when

This is not the case without the completeness assumption; for counterexamples one could consider any open bounded subset of a Euclidean space with the standard Riemannian metric.

An (affine) connection is an additional structure on a Riemannian manifold that defines differentiation of one vector field with respect to another.

An ant living in a Riemannian manifold walking straight ahead without making any effort to accelerate or turn would trace out a geodesic.

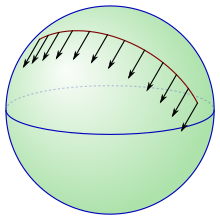

Parallel transport is a way of moving vectors from one tangent space to another along a curve in the setting of a general Riemannian manifold.

The images below show parallel transport induced by the Levi-Civita connection associated to two different Riemannian metrics on the punctured plane

The Riemann curvature tensor measures precisely the extent to which parallel transporting vectors around a small rectangle is not the identity map.

[28] The Riemann curvature tensor is 0 at every point if and only if the manifold is locally isometric to Euclidean space.

plays a defining role in the theory of Einstein manifolds, which has applications to the study of gravity.

Formally, given an inner product ge on the tangent space at the identity, the inner product on the tangent space at an arbitrary point p is defined by where for arbitrary x, Lx is the left multiplication map G → G sending a point y to xy.

The Levi-Civita connection and curvature of a general left-invariant Riemannian metric can be computed explicitly in terms of ge, the adjoint representation of G, and the Lie algebra associated to G.[36] These formulas simplify considerably in the special case of a Riemannian metric which is bi-invariant (that is, simultaneously left- and right-invariant).

Left- and bi-invariant metrics on Lie groups are an important source of examples of Riemannian manifolds.

Berger spheres, constructed as left-invariant metrics on the special unitary group SU(2), are among the simplest examples of the collapsing phenomena, in which a simply-connected Riemannian manifold can have small volume without having large curvature.

Given a Lie group G with compact subgroup K which does not contain any nontrivial normal subgroup of G, fix any complemented subspace W of the Lie algebra of K within the Lie algebra of G. If this subspace is invariant under the linear map adG(k): W → W for any element k of K, then G-invariant Riemannian metrics on the coset space G/K are in one-to-one correspondence with those inner products on W which are invariant under adG(k): W → W for every element k of K.[44] Each such Riemannian metric is homogeneous, with G naturally viewed as a subgroup of the full isometry group.

The above example of Lie groups with left-invariant Riemannian metrics arises as a very special case of this construction, namely when K is the trivial subgroup containing only the identity element.

Every Riemannian symmetric space is homogeneous, and consequently is geodesically complete and has constant scalar curvature.

Grassmannian manifolds also carry natural Riemannian metrics making them into symmetric spaces.

The seventh exception is the study of 'generic' Riemannian manifolds with no particular symmetry, as reflected by the maximal possible holonomy group.

[citation needed] Further, a strong Riemannian manifold for which all closed and bounded subsets are compact might not be geodesically complete.