Right-to-work law

[2][3] In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that agency shop arrangements for public sector employees were unconstitutional in the case Janus v. AFSCME.

[4] According to the American Enterprise Institute, the modern usage of the term right to work was coined by Dallas Morning News editorial writer William Ruggles in 1941.

[5] According to PandoDaily, the modern term was coined by Vance Muse, a Republican Party operative who headed the Christian American Association, an early right-to-work advocacy group, to replace the term "American Plan" after it became associated with the anti-union violence of the First Red Scare.

President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal had prompted many U.S. Supreme Court challenges, including those regarding the constitutionality of the National Industry Recovery Act (NIRA) of 1933.

... [A] statute which attempts to confer such power undertakes an intolerable and unconstitutional interference with personal liberty and private property.

An opponent to the union bargain is forced to financially support an organization for which they did not vote in order to receive monopoly representation for which they have no choice.

[20] The agency shop portion of this had previously been contested with support of National Right to Work Legal Defense Foundation in Communications Workers of America v. Beck, resulting in "Beck rights" preventing agency fees from being used for expenses outside of collective bargaining if the non-union worker notifies the union of their objection.

Opponents, such as Richard Kahlenberg,[2][23] have argued that right-to-work laws simply "gives employees the right to be free riders—to benefit from collective bargaining without paying for it.

"[24][25] Benefits the dissenting union members would receive despite not paying dues also include representation during arbitration proceedings.

[26] In Abood v. Detroit BoE, the Supreme Court of the United States permitted public-sector unions to charge non-members agency fees so that employees in the public sector could be required to pay for the costs of representation, even as they opted not to be a member, as long as these fees are not spent on the union's political or ideological agenda.

[24] In December 2012, libertarian writer J. D. Tuccille wrote in Reason: "I consider the restrictions right-to-work laws impose on bargaining between unions and businesses to violate freedom of contract and association.

I'm disappointed that the state has, once again, inserted itself into the marketplace to place its thumb on the scale in the never-ending game of playing business and labor off against one another.

[29] A 2019 paper in the American Economic Review by economists from MIT, Stanford, and the U.S. Census Bureau, which surveyed 35,000 U.S. manufacturing plants, found that "the business environment, as measured by right-to-work laws, boosts incentive management practices.

"[30] According to a 2020 study published in the American Journal of Sociology, right-to-work laws lead to greater economic inequality by indirectly reducing the power of labor unions.

[33] Holmes compared counties close to the border between states with and without right-to-work laws, thereby holding constant an array of factors related to geography and climate.

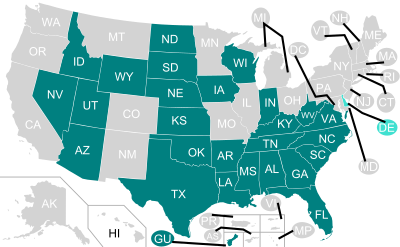

Seaford passed a right-to-work ordinance in 2018, despite the State Solicitor disputing the authority of local governments to do so under Delaware law.

[60][61][62] In a 2022 referendum, voters in Illinois approved a state constitutional amendment establishing a right to collective bargaining.

[74] New Mexico law previously did not explicitly prohibit nor allow mandatory union membership as a condition of employment at the statewide level, thereby leaving it up to local jurisdictions to establish their own right-to-work policies.

[80] In 2020, New Mexico's legislature passed House Bill 364 that authorizes and promotes the use of card check protocols for workers considering organizing into a labor union.