Right-hand rule

In mathematics and physics, the right-hand rule is a convention and a mnemonic, utilized to define the orientation of axes in three-dimensional space and to determine the direction of the cross product of two vectors, as well as to establish the direction of the force on a current-carrying conductor in a magnetic field.

The various right- and left-hand rules arise from the fact that the three axes of three-dimensional space have two possible orientations.

The right-hand rule dates back to the 19th century when it was implemented as a way for identifying the positive direction of coordinate axes in three dimensions.

William Rowan Hamilton, recognized for his development of quaternions, a mathematical system for representing three-dimensional rotations, is often attributed with the introduction of this convention.

[1] Josiah Willard Gibbs recognized that treating these components separately, as dot and cross product, simplifies vector formalism.

This transition led to the prevalent adoption of the right-hand rule in the contemporary contexts.

In specific, Gibbs outlines his intention for establishing a right-handed coordinate system in his pamphlet on vector analysis [3].

[4] The right-hand rule in physics was introduced in the late 19th century by John Fleming in his book Magnets and Electric Currents.

For left-handed coordinates, the above description of the axes is the same, except using the left hand; and the ¼ turn is clockwise.

Reversing two axes amounts to a 180° rotation around the remaining axis, also preserving the handedness.

If the thumb is pointing north, Earth rotates according to the right-hand rule (prograde motion).

This causes the Sun, Moon, and stars to appear to revolve westward according to the left-hand rule.

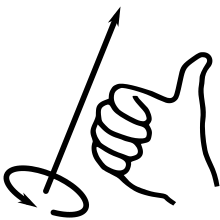

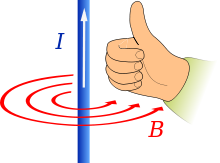

Ampère's right-hand grip rule,[7] also called the right-hand screw rule, coffee-mug rule or the corkscrew-rule; is used either when a vector (such as the Euler vector) must be defined to represent the rotation of a body, a magnetic field, or a fluid, or vice versa, when it is necessary to define a rotation vector to understand how rotation occurs.

Ampère was inspired by fellow physicist Hans Christian Ørsted, who observed that needles swirled when in the proximity of an electric current-carrying wire and concluded that electricity could create magnetic fields.

This rule is used in two different applications of Ampère's circuital law: The cross product of two vectors is often taken in physics and engineering.

For example, as discussed above, the force exerted on a moving charged particle when moving in a magnetic field B is given by the magnetic term of Lorentz force: The direction of the cross product may be found by application of the right-hand rule as follows: For example, for a positively charged particle moving to the north, in a region where the magnetic field points west, the resultant force points up.

A list of physical quantities whose directions are related by the right-hand rule is given below.

Rather, the definition depends on chiral phenomena in the physical world, for example the culturally transmitted meaning of right and left hands, a majority human population with dominant right hand, or certain phenomena involving the weak force.

right-handed coordinates on the right.