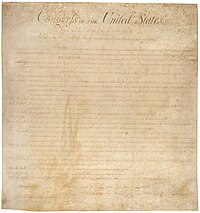

Right to petition in the United States

Although often overlooked in favor of other more famous freedoms, and sometimes taken for granted,[1] many other civil liberties are enforceable against the government only by exercising this basic right.

The right extends to the "approach of citizens or groups of them to administrative agencies (which are both creatures of the legislature, and arms of the executive) and to courts, the third branch of Government.

It required that a Commission be provided at every Parliament to "hear by petition delivered to them, the Complaints of all those that will complain them of such Delays or Grievances done to them".

[10] In reference to violation of the right to petition, the Prince of Orange had the following to say in his Declaration of Reason, "And yet it cannot be pretended, that any Kings, how great soever their Power has been, and how arbitrary and despotick soever they have been in the Exercise of it, have ever reckoned it a Crime for their Subjects to come, in all Submission and Respect, and in a due Number not exceeding the Limits of the Law, and represent to them the Reasons that made it impossible for them to obey their Orders."

The Prince of Orange had the following to say about arbitrary rule (dictatorship) in his Declaration of Reason, "that the King can intirely suspend the Execution of those Laws relating to Treason or Felony, unless it is pretended, that he is cloathed with a despotick and arbitrary Power, and that the Lives, Liberties, Honours, and Estates of the Subjects, depend wholly on his goodwill and Pleasure, and are intirely subject to him; which must infallibly follow on the King's having a Power to suspend the Execution of Laws, and to dispense with them."

[13] Starting in 1836, the House of Representatives adopted a series of gag rules that automatically tabled indefinitely all such anti-slavery petitions, and prohibited their discussion.

Former president John Quincy Adams and other Representatives eventually achieved repeal of these rules in 1844 on the basis that it was contrary to the Constitutional right (in the First Amendment) to "petition the government for the redress of grievances".

[15] Civil litigation between two private individuals or entities is considered to be a right to a peititon, since they are asking the government's court system to remedy their problems.

This view was rejected by the United States Supreme Court in 1984: Nothing in the First Amendment or in this Court's case law interpreting it suggests that the rights to speak, associate, and petition require government policymakers to listen or respond to communications of members of the public on public issues.

Although this case proceeds under the Petition Clause, Guarnieri just as easily could have alleged that his employer retaliated against him for the speech contained within his grievances and lawsuit.

It is not necessary to say that the two Clauses are identical in their mandate or their purpose and effect to acknowledge that the rights of speech and petition share substantial common ground.

In those circumstances the Court found "no sound basis for granting greater constitutional protection to statements made in a petition … than other First Amendment expressions."

There may arise cases where the special concerns of the Petition Clause would provide a sound basis for a distinct analysis; and if that is so, the rules and principles that define the two rights might differ in emphasis and formulation.The law of South Dakota prohibits sex offenders from circulating petitions, carrying a maximum potential sentence of one year in jail and a $2,000 fine.

[23] The right of government employees to address grievances with their employer over work-related matters can be restricted to administrative processes under Supreme Court precedent.