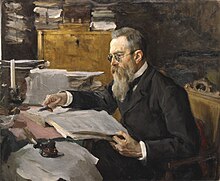

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

This style employed Russian folk song and lore along with exotic harmonic, melodic and rhythmic elements in a practice known as musical orientalism, and eschewed traditional Western compositional methods.

He undertook a rigorous three-year program of self-education and became a master of Western methods, incorporating them alongside the influences of Mikhail Glinka and fellow members of The Five.

The composer's mother, Sofya Vasilievna Rimskaya-Korsakova (1802–1890), was also born as an illegitimate daughter of a peasant serf and Vasily Fedorovich Skaryatin, a wealthy landlord who belonged to the noble Russian family that originated during the 16th century.

[17] He found time to read the works of Homer, William Shakespeare, Friedrich Schiller and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe; he saw London, Niagara Falls, and Rio de Janeiro during his stops in port.

[17] "Thoughts of becoming a musician and composer gradually left me altogether", he later recalled; "distant lands began to allure me, somehow, although, properly speaking, naval service never pleased me much and hardly suited my character at all.

[36] Though Rimsky-Korsakov later found Balakirev's influence stifling, and broke free from it,[37] this did not stop him in his memoirs from extolling the older composer's talents as a critic and improviser.

"[56] To prepare himself, and to stay at least one step ahead of his students, he took a three-year sabbatical from composing original works, and assiduously studied at home while he lectured at the Conservatory.

[41] "Her last years were dedicated to issuing her husband's posthumous literary and musical legacy, maintaining standards for performance of his works ... and preparing material for a museum in his name.

[73] Rimsky-Korsakov's studies and his change in attitude regarding music education brought him the scorn of his fellow nationalists, who thought he was throwing away his Russian heritage to compose fugues and sonatas.

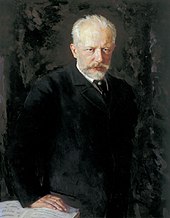

About the quartet and the symphony, Tchaikovsky wrote to his patroness, Nadezhda von Meck, that they "were filled with a host of clever things but ... [were] imbued with a dryly pedantic character".

[90] Belyayev was one of a growing coterie of Russian nouveau-riche industrialists who became patrons of the arts in mid- to late-19th century Russia; their number included railway magnate Savva Mamontov and textile manufacturer Pavel Tretyakov.

[89] He noted that these three works "show a considerable falling off in the use of contrapuntal devices ... [replaced] by a strong and virtuoso development of every kind of figuration which sustains the technical interest of my compositions".

To select which composers to assist with money, publication or performances from the many who now appealed for help, Belyayev set up an advisory council made up of Glazunov, Lyadov and Rimsky-Korsakov.

[112] In March 1889, Angelo Neumann's traveling "Richard Wagner Theater" visited Saint Petersburg, giving four cycles of Der Ring des Nibelungen there under the direction of Karl Muck.

He would fume for days afterwards when he heard pianist Felix Blumenfeld play Debussy's Estampes and write in his diary about them, "Poor and skimpy to the nth degree; there is no technique, even less imagination.

[126] Due in part to widespread press coverage of these events,[127] an immediate wave of outrage against the ban arose throughout Russia and abroad; liberals and intellectuals deluged the composer's residence with letters of sympathy,[128] and even peasants who had not heard a note of Rimsky-Korsakov's music sent small monetary donations.

[130] In April 1907, Rimsky-Korsakov conducted a pair of concerts in Paris, hosted by impresario Sergei Diaghilev, which featured music of the Russian nationalist school.

[132] In 1908, he died at his Lubensk estate near Luga (modern day Plyussky District of Pskov Oblast), and was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg, next to Borodin, Glinka, Mussorgsky and Stasov.

He employed Orthodox liturgical themes in the Russian Easter Festival Overture, folk song in Capriccio Espagnol and orientalism in Scheherazade, possibly his best known work.

Conversely, his care about how or when in a composition he used these scales made him seem conservative compared with later composers like Igor Stravinsky, though they were often building on Rimsky-Korsakov's work.

The best-known of these excerpts is probably "Flight of the Bumblebee" from The Tale of Tsar Saltan, which has often been heard by itself in orchestral programs, and in countless arrangements and transcriptions, most famously in a piano version made by Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff.

The best-known ones in the West, and perhaps the finest in overall quality, are mainly programmatic in nature — in other words, the musical content and how it is handled in the piece is determined by the plot or characters in a story, the action in a painting or events reported through another non-musical source.

While a principle of highlighting "primary hues" of instrumental color remained in place, it was augmented in the later works by a sophisticated cachet of orchestral effects, some gleaned from other composers including Wagner, but many invented by himself.

"[145] This statement was not true for Glinka, who studied Western music theory assiduously with Siegfried Dehn in Berlin before he composed his opera A Life for the Tsar.

[147] One point Stasov omitted purposely, which would have disproved his statement completely, was that at the time he wrote it, Rimsky-Korsakov had been pouring his "book learning" into students at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory for over a decade.

[150]Taruskin points out this statement, which Rimsky-Korsakov wrote while Borodin and Mussorgsky were still alive, as proof of his estrangement from the rest of The Five and an indication of the kind of teacher he eventually became.

[154] Apart from Glazunov and Stravinsky, students who later found fame included Anatoly Lyadov, Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov, Alexander Spendiaryan, Sergei Prokofiev, Ottorino Respighi, Witold Maliszewski, Mykola Lysenko, Artur Kapp, and Konstanty Gorski.

It was generally assumed that with Prince Igor, Rimsky-Korsakov edited and orchestrated the existing fragments of the opera while Glazunov composed and added missing parts, including most of the third act and the overture.

Rimsky-Korsakov may have foreseen questions over his efforts when he wrote, If Mussorgsky's compositions are destined to live unfaded for fifty years after their author's death (when all his works will become the property of any and every publisher), such an archeologically accurate edition will always be possible, as the manuscripts went to the Public Library on leaving me.

[168] Musicologists and Slavicists have long recognized that Rimsky-Korsakov was an ecumenical artist whose folklore-inspired operas take up such issues as the relationship between paganism and Christianity and the seventeenth-century schism in the Orthodox Church.