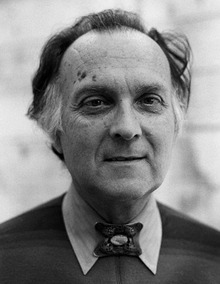

Robert Duncan (poet)

During the later part of his life, Duncan's work, published by City Lights and New Directions, came to be distributed worldwide, and his influence as a poet is evident today in both mainstream and avant-garde writing.

There were terms for his adoption that had to be met: he had to be born at the time and place appointed by the astrologers, his mother was to die shortly after giving birth, and he was to be of Anglo-Saxon Protestant descent.

[9] His childhood was stable, and his parents were popular and social members of their community—Edwin was a prominent architect and Minnehaha devoted much of her time to volunteering and serving on committees.

He grew up surrounded by the occult in one form or another; he was well aware of the circumstances of his fated birth and adoption and his parents carefully interpreted his dreams.

In Roots and Branches, his second major book, he wrote: "I had the double reminder always, the vertical and horizontal displacement in vision that later became separated, specialized into a near and a far sight.

He thrived as storyteller, poet, and fledgling bohemian, but by his sophomore year he had begun to drop classes and had quit attending obligatory military drills.

[citation needed] In 1938, he briefly attended Black Mountain College,[6] but left after a dispute with faculty over the Spanish Civil War.

The essay, in which Duncan compared the plight of homosexuals with that of African Americans and Jews, was published in Dwight Macdonald's journal politics.

[citation needed] After the end of World War II, Duncan returned to the Bay Area, where he met the young Gerald M. Ackerman.

[14] Duncan returned to San Francisco in 1945 and was befriended by Helen Adam, Madeline Gleason, Lyn Brockway, and Kenneth Rexroth (with whom he had been in correspondence for some time).

He returned to Berkeley to study Medieval and Renaissance literature and cultivated a reputation as a shamanistic figure in San Francisco poetry and artistic circles.

[citation needed] During the 1960s, Duncan achieved considerable artistic and critical success with three books; The Opening of the Field (1960), Roots and Branches (1969), and Bending the Bow (1968).

His poetry is modernist in its preference for the impersonal, mythic, and hieratic, but Romantic in its privileging of the organic, the irrational and primordial, the not-yet-articulate blindly making its way into language like salmon running upstream: Neither our vices nor our virtues further the poem.

His friend and fellow poet Michael Palmer writes about this time in his essay "Ground Work: On Robert Duncan": The story is well-known in poetry circles: around 1968, disgusted by his difficulties with publishers and by what he perceived as the careerist strategies of many poets, Duncan vowed not to publish a new collection for fifteen years.