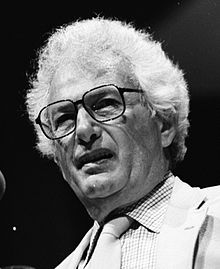

Robert Gottlieb

While at Simon & Schuster and Knopf, he notably edited books by Joseph Heller, Jessica Mitford, Lauren Bacall, Salman Rushdie, Toni Morrison, John le Carré, and Robert Caro, among others.

Robert Gottlieb was born in 1931 to a Jewish family[5] in Manhattan, New York City, where he grew up on the Upper West Side.

Gottlieb, who had been working seasonally at Macy's and translating from French on a freelance basis, had actively looked for a publishing career since leaving Cambridge.

[12] With the absence of Goodman, Simon, and senior editor Albert Leventhal, the firm's business chief named Gottlieb editorial director in 1959.

[20] When published in October 1961, more than a year after its initial deadline, the book received mixed reviews, with praise from Newsweek, but pause from Time.

"[21][22] Gottlieb and Bourne capitalized on the positive reviews from some publications and from famous writers— a group that included Harper Lee, Art Buchwald, and Nelson Algren, among others— by aggressively purchasing ads in the Times and other periodicals to display the praise.

[23] Though the hardcover edition did not sell well enough to reach the Best Seller list, it did manage to run for six printings before Gottlieb sold the paperback rights to low-cost publisher Dell for $32,000.

[24] Dell sold 800,000 copies by September 1962 and the combined book sales exceeded 1.1 million by April 1963, a year and a half after the initial publishing.

[24] In the late 1960s, after the positive experience of Catch-22, Heller followed Gottlieb to Knopf to publish a book version of his Broadway play, We Bombed in New Haven.

Originally titled Catch-18, Heller, Gottlieb and Donadio sensed a need to change the name so as not to compete with Leon Uris's then-upcoming war novel Mila 18.

[26] Gottlieb vociferously disputed that narrative as a lie, claiming that he distinctly remembered calling Heller in the middle of the night to tell him that "22" was funnier than "18.

"[27] Heller felt that the titular 22 may have derived from his offering to call the airplanes in the book "B-22s," after a legal team suggested that the military may object to usage of the name "B-25.

"[28] Former editor and Simon & Schuster historian Peter Schwed notes that Gottlieb had some luck in the early 1960s in recognizing publishing potential where others did not.

Delderfield's A Horseman Riding By, which every American publisher, including Simon & Schuster, had declined to try to transfer to the U.S.[13] With a publisher-favorable contract on the expectation that it wouldn't perform, the book and other Delderfield books eventually sold millions in the U.S.[13] Gottlieb also bought the rights to publish John Lennon's farce, In His Own Write, shortly before Beatlemania reached the United States.

[13] Journalist William Shirer began writing his best-selling popular history book, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich before Gottlieb's involvement in the company, working with editor Joseph Barnes.

She decided to use the attention to complete a book on the American funerary industry that she had researched on and off since 1958, after her husband, civil rights lawyer Robert Treuhaft, mentioned that his union clients' funeral expenses seemed to be rising.

[34] It was so influential that Robert F. Kennedy told Mitford that he initially chose the least ornate model for his brother's coffin, due to the extortionary practices she had documented.

[36][37] Gottlieb suffered some ignominy for rejecting A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole, a book that later won the Pulitzer Prize when it was published posthumously eleven years after the author's death by suicide.

[41] The author's mother, Thelma Toole, who had convinced a small academic press to publish the novel with a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, fixated on Gottlieb as a source of her son's suicidal despair.

Toole originally blamed Gottlieb for keeping her son "on tenterhooks" with their extended correspondence, but quickly began to use antisemitic canards, calling the editor "a Jewish creature.

"[40][42] Aside from A Confederacy of Dunces, Gottlieb also wrote that he had regretted his rejections of The Collector by John Fowles and Larry McMurtry's Lonesome Dove (while at Knopf).

[44] Two years later, amidst shakeups that removed Grace Mirabella from Vogue and Louis Gropp from House & Garden, Newhouse asked Gottlieb to replace Shawn as editor of The New Yorker.

Gottlieb edited novels by John Cheever, Doris Lessing, Chaim Potok, Charles Portis, Salman Rushdie, John Gardner, Len Deighton, John le Carré, Ray Bradbury, Elia Kazan, Margaret Drabble, Michael Crichton, Mordecai Richler, and Toni Morrison, and non-fiction books by Bill Clinton, Janet Malcolm, Katharine Graham, Nora Ephron, Katharine Hepburn, Barbara Tuchman, Jessica Mitford, Robert Caro, Antonia Fraser, Lauren Bacall, Liv Ullmann, Paul Simon, Bob Dylan, Bruno Bettelheim, Carl Schorske, and many others.

[3] In a 2001 LA Times article by Linton Weeks, Gottlieb was referred by an unnamed author he had worked with as "the nicest guy in the world.

[50] In Turn Every Page, author Robert Caro speaks of his and Gottlieb's mutually terrible "tempers," which are driven, he feels, from a desire to find the best version of the book at hand.