Robert de Stretton

[1] A client of Edward, the Black Prince, he became a "notorious figure"[2] because it was alleged that he was illiterate, although this is now largely discounted as unlikely, as he was a relatively efficient administrator.

Fletcher claimed that the Eyryk family were "undoubtedly seated at Stretton Magna at an early date, and held land there under Leicester Abbey,"[9] providing a family tree, based on research by Nichols, that pushed the connection back to the reign of Henry III (1216-1272), while the recent Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article asserts that Robert himself held the manor in the 1370s.

The relevant Victoria County History volumes provides only limited corroboration, showing the pattern of land holding at Great Stretton as complicated: there was a high degree of subinfeudation by the late 13th century.

The existence of the clerk Richard Heirick in the late 13th century makes clear that the Eyryks, like many other lower landed gentry families, were accustomed to some of their young men seeking ordination.

[3] Fletcher, in his earlier biography, asserted that he "became Doctor of Laws, one of the auditors of the Rota in the Court of Rome and Chaplain to Edward the Black Prince"[11] - the academic claim derived from Henry Wharton's Anglia Sacra.

Two nuncios were sent to promote talks between the James of Bourbon, the Constable of France and Edward III of England, with a view to averting hostilities in Gascony,[22] where the Black Prince had been conducting a hugely destructive chevauchée.

Robert de Stretton, addressed as canon of Lincoln, was one of an English deputation nominated by the Pope to support the nuncios in their mission.

G. R. Owst, pioneering historian of preaching in the period, fell upon Stretton's case with glee, as confirming some of the most damning allegations about clerical incompetence made by contemporary preachers: This judgement largely, if tendentiously, reflected Fletcher's narrative.

This is mainly based on the Vitae archiepiscoporum Cantuariensium, a 14th-century work attributed to Stephen Birchington, which became established as the key narrative because it was reproduced by Henry Wharton, a highly respected 17th century historian and bibliographer.

This version of events then has the Church bullied, despite further failures on Stretton's part, into conceding his consecration, a papal bull forcing Simon Islip, the Archbishop of Canterbury, to depute the task to the Bishops of London and Rochester, which they performed "with evident reluctance.

[3] The papal bull of 22 April 1360 merely says that Stretton was forced to plead his case because he had allowed himself to be elected without realising that the Pope had reserved the see of Coventry and Lichfield.

[3] Wharton included in Anglia Sacra a continuation of the history of Lichfield by William Whitlocke, which describes Stretton as eximius vir – an exceptional man – and goes on to make the probably exaggerated claims for his attainments in jurisprudence noted above.

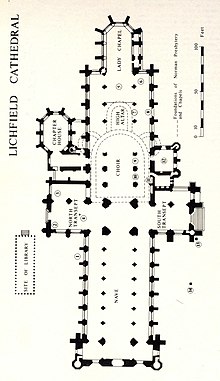

A serious problem for 14th century bishops was that the major offices at the cathedral, which should have provided the core episcopal staff, were largely filled by absentees.

Chancellors were absentees from 1364: from 1380 the post was used to reward another Italian bishop, Pileus de Prata, Cardinal priest of Santa Prassede.

[28] Stretton was fortunate in having a cadre of able canons who served the cathedral and diocese reliably over decades, partly filling the administrative gap.

Hugh of Hopwas, presumably a local man, was a fellow client of the Black Prince:[25] he became a canon in 1352,[29] well before Stretton's election, in which he must have participated.

Richard de Birmingham, official of Bishop Stretton and an effective member of the chapter for 20 years,[25] held the prebend of Pipa Minor[31] and was Archdeacon of Coventry in the 1360s.

However, much of the work of the cathedral and diocese was done by vicars, essentially clerics hired to deputise for the chapter, who received "commons" or subsistence allowance of 1½d.

In 1362 he confirmed the election of Maud or Matilda Botetourt as Abbess of Polesworth Abbey in Warwickshire, despite her being only 20 years old and so under the requisite age,[32] and forbade further reference to the issue.

[32] The issues at Shrewsbury in the 1374 certainly included family connections, as the problematic appointment was of a Master Robert de Stretton as Dean of St Chad's Church.

For reasons unknown – or, at least, not disclosed in Stretton's register – a large body of heavily armed townspeople attacked his entourage while he was conducting an inspection of Repton Priory.

They first surrounded the priory but at 11 pm broke into the premises and terrorised Stretton and his staff for two hours, shooting arrows through the windows of the rooms where they sheltered.

Stretton pronounced excommunication on the culprits and then fled north to Alfreton, where he interdicted the town of Repton and St. Wystan's, the parish church.

An extant but undated petition of Edward III's reign, complaining of unpunished threatening behaviour and arson by Augustinian canons from the priory, may provide an explanation of the townspeople's revolt against the Church authorities.

He was absent from parliament from 1376 and had become completely blind by September 1381, when the prior and chapter of Canterbury (there being no archbishop) ordered him to appoint a Coadjutor bishop.