Rochester Castle

During the Rebellion of 1088 over the succession to the English throne, Odo supported Robert Curthose, the Conqueror's eldest son, against William Rufus.

The castle had been greatly damaged, with breaches in the outer walls and one corner of the keep collapsed, and hunger eventually forced the defenders' hand.

John died and was succeeded by his son King Henry III in 1216; the next year, the war ended and the castle was taken under direct royal control.

[1] Archaeologist Tom McNeill has suggested that these earliest castles in England may have been purely military, built to contain a large number of troops in hostile territory.

A significant number of Norman barons objected to dividing Normandy and England, and Bishop Odo supported Robert's claim to the English throne.

Odo, Eustace, Count of Boulogne, and Robert of Bellême, son of the Earl of Shrewsbury, were allowed to march away with their weapons and horses but their estates in England were confiscated.

William the Conqueror had granted Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury, the manor of Haddenham in Buckinghamshire – which as of the Domesday Survey had an annual income of £40 – for the duration of his life.

According to archaeologist Oliver Creighton, when castles were positioned close to churches or cathedrals it suggested a link between the two, and in this case, both were owned by the Bishop of Rochester.

[20] Defeat at the Battle of Bouvines in July 1214 marked the end of John's ambitions to retake Normandy and exacerbated the situation in England.

[22] John persuaded Stephen Langton, the new Archbishop of Canterbury, to give control of Rochester Castle to a royal constable, Reginald de Cornhill.

[23] Shortly after the treaty the agreement between John and Langton to appoint a royal constable in charge of Rochester Castle was dissolved, returning control to the archbishop.

In a letter that year to justiciar Hubert de Burgh John expressed his frustration towards Langton, calling him "a notorious traitor to us, since he did not render our castle of Rochester to us in our so great need".

Royal forces had arrived ahead of John and entered the city on 11 October, taking it by surprise and laying siege to the castle.

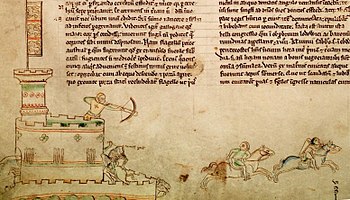

The Barnwell chronicler claimed they smashed a hole in the castle's outer walls; Roger of Wendover asserted they were ineffective and that John turned to other methods to breach the defences.

John ordered Hugh de Burgh to "send to us with all speed by day and night forty of the fattest pigs of the sort least good for eating to bring fire beneath the tower".

Savaric de Mauléon, one of John's captains, persuaded the king otherwise, concerned that similar treatment would be shown to royal garrisons by the rebels.

[29] Prince Louis of France, son of Philip II, was invited by the barons to become the new leader of the rebellion and become king in the event of their victory.

[35] A baronial army led by Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Hertford, laid siege to the castle on 17 April that year.

According to one contemporary source, the besiegers were about to dig a mine beneath the tower, but the siege was abandoned on 26 April when the earls received news of a relief force led by Henry III and his son, Prince Edward.

[34] Though the garrison had held out within the keep, the rest of the castle had incurred severe damage, but no attempt was made to carry out repairs until the reign of Edward III (1327–1377).

In 1281 John of Cobham, the constable, was granted permission to pull down the castle's hall and chambers which had been left as burnt-out ruins after the 1264 siege.

There were unsuccessful plans in 1780 to reuse Rochester Castle as an army barracks, after the commander of the Royal Engineers for Chatham, Colonel Hugh Debbieg, asked the Child family for permission.

Through the words of one of his characters, Dickens described the castle as a "glorious pile – frowning wall – tottering arches – dark nooks – crumbling stones".

[69] From across the River Medway, the twin landmarks of Rochester's castle and cathedral would have dominated the medieval landscape, symbolic of the authority of the church and nobility in the period.

[72] Since its construction it has undergone limited alteration, aside from the rebuilding of one corner, and although now in a state of ruin it remains significantly intact and is considered one of the most important surviving 12th-century keeps in England and France.

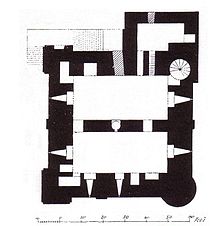

A stone staircase began on the west side of the keep before turning and meeting the forebuilding, which could be entered by crossing a drawbridge across a gap 9 feet (2.7 m) wide.

Rochester's keep bears testament to a developing complexity, and provides an early example of a keep divided into separate areas for the lord and his retinue.

A tower containing a postern gate was located in the north-west corner of the enclosure, built at the close of the 14th century to guard the bridge over the Medway.

At the eastern end of this wall, near the southern corner of the castle, is a two-storey rounded tower 30 feet (9.1 m) in diameter dating from the early 13th century.

It was built to fill the breach in the curtain wall caused when John's army besieged the castle and to reinforce a weak point in the defences.