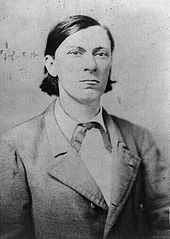

Roger A. Pryor

"[1][2] He became a law partner with Benjamin F. Butler (based in Boston), noted in the South as a hated Union general during the war.

In 1877 he was chosen to give a Decoration Day address, in which, according to one interpretation, he vilified Reconstruction and promoted the Lost Cause, while reconciling the noble soldiers as victims of politicians.

[3][4] In 1890 he joined the Sons of the American Revolution, one of the new heritage societies that was created following celebration of the United States Centennial.

[5] On April 10, 1912, he was appointed official referee by the appellate division of the state Supreme Court, where he served until his death.

She was a writer and had several works: histories, memoirs, and novels, published by the Macmillan Company in the first decade of the twentieth century.

For a few years, Pryor worked at journalism, serving on the editorial staffs of the Washington Union in 1852 and the Daily Richmond Enquirer in 1854.

He became known as a fiery and eloquent advocate of slavery, southern states' rights, and secession; although he and his wife did not personally own slaves, they came from the slaveholding class.

[15] His advocacy of the institution was an example of how, in a "slave society" like Virginia, slavery both powered the economy and underlay the entire social framework.

[16] In 1859, Pryor was elected as a Democrat to the U.S. House of Representatives; he filled the vacancy in Virginia's 4th District caused by the death of William O. Goode.

"[18] The incident was widely publicized in the Northern press, which portrayed Pryor's refusal to duel as a coup for the North — and as a cowardly humiliation of a Southern "fire eater".

"[21] Pryor almost became the first casualty of the Civil War - while visiting Fort Sumter as an emissary, he assumed a bottle of potassium iodide in the hospital was medicinal whiskey and drank it; his mistake was realized in time for Union doctors to pump his stomach and save his life.

His brigade fought in the Peninsula Campaign and at Second Manassas, where it became detached in the swirling fighting and temporarily operated under Stonewall Jackson.

[23] Pryor proved inept as a division commander, and Union troops flanked his position, causing them to fall back in disorder.

Following his adequate performance at the Battle of Deserted House, later in 1863 Pryor resigned his commission and his brigade was broken up, its regiments being reassigned to other commands.

Pryor learned to operate in New York Democratic Party politics, where he was prominent among influential southerners who became known as "Confederate carpetbaggers.

[6][15] Pryor was elected as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1876, a year before the federal government pulled its last military forces out of the South and ended Reconstruction.

Chosen by the Democratic Party for the important Decoration Day address in 1877, after the national compromise that resulted in the federal government pulling its troops out of the South, Pryor vilified Reconstruction and promoted the Lost Cause.

He referred to all the soldiers as noble victims of politicians, although he had been one who gave fiery speeches in favor of secession and war.

[5] In December 1890, Pryor joined the New York chapter of the new heritage/lineage organization, Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), for male descendants of participants in the war.

In retirement, Pryor was appointed on April 10, 1912, as official referee by the appellate division of the New York State Supreme Court.

[31] Like her husband, Sarah Pryor helped found lineage and heritage organizations, including Preservation of the Virginia Antiquities (since 2009 named Preservation Virginia); the National Mary Washington Memorial Association; the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR); and the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America.