Roger Bacon

[4][5] His linguistic work has been heralded for its early exposition of a universal grammar, and 21st-century re-evaluations emphasise that Bacon was essentially a medieval thinker, with much of his "experimental" knowledge obtained from books in the scholastic tradition.

[12] By the late 1250s, resentment against the king's preferential treatment of his émigré Poitevin relatives led to a coup and the imposition of the Provisions of Oxford and Westminster, instituting a baronial council and more frequent parliaments.

Pope Urban IV absolved the king of his oath in 1261 and, after initial abortive resistance, Simon de Montfort led a force, enlarged due to recent crop failures, that prosecuted the Second Barons' War.

[25] For a time, Bacon was finally able to get around his superiors' interference through his acquaintance with Guy de Foulques, bishop of Narbonne, cardinal of Sabina, and the papal legate who negotiated between England's royal and baronial factions.

[26] Clement's reply of 22 June 1266 commissioned "writings and remedies for current conditions", instructing Bacon not to violate any standing "prohibitions" of his order but to carry out his task in utmost secrecy.

[26] While faculties of the time were largely limited to addressing disputes on the known texts of Aristotle, Clement's patronage permitted Bacon to engage in a wide-ranging consideration of the state of knowledge in his era.

[19] In 1267 or '68, Bacon sent the Pope his Opus Majus, which presented his views on how to incorporate Aristotelian logic and science into a new theology, supporting Grosseteste's text-based approach against the "sentence method" then fashionable.

This was traditionally ascribed to Franciscan Minister General Jerome of Ascoli, probably acting on behalf of the many clergy, monks, and educators attacked by Bacon's 1271 Compendium Studii Philosophiae.

[1] Modern scholarship, however, notes that the first reference to Bacon's "imprisonment" dates from eighty years after his death on the charge of unspecified "suspected novelties"[29][30] and finds it less than credible.

[2][35] Medieval European philosophy often relied on appeals to the authority of Church Fathers such as St Augustine, and on works by Plato and Aristotle only known at second hand or through Latin translations.

In Roger Bacon's writings, he upholds Aristotle's calls for the collection of facts before deducing scientific truths, against the practices of his contemporaries, arguing that "thence cometh quiet to the mind".

He argued that, rather than training to debate minor philosophical distinctions, theologians should focus their attention primarily on the Bible itself, learning the languages of its original sources thoroughly.

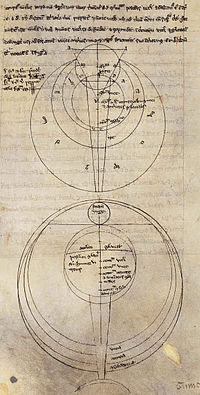

Bacon's 1267 Greater Work, the Opus Majus,[n 4] contains treatments of mathematics, optics, alchemy, and astronomy, including theories on the positions and sizes of the celestial bodies.

[42] It was not intended as a complete work but as a "persuasive preamble" (persuasio praeambula), an enormous proposal for a reform of the medieval university curriculum and the establishment of a kind of library or encyclopedia, bringing in experts to compose a collection of definitive texts on these subjects.

[44] In this work Bacon criticises his contemporaries Alexander of Hales and Albertus Magnus, who were held in high repute despite having only acquired their knowledge of Aristotle at second hand during their preaching careers.

[39] Drawing on ancient Greek and medieval Islamic astronomy recently introduced to western Europe via Spain, Bacon continued the work of Robert Grosseteste and criticised the then-current Julian calendar as "intolerable, horrible, and laughable".

In Part V of the Opus Majus, Bacon discusses physiology of eyesight and the anatomy of the eye and the brain, considering light, distance, position, and size, direct and reflected vision, refraction, mirrors, and lenses.

[56][n 5] The most telling passage reads: We have an example of these things (that act on the senses) in [the sound and fire of] that children's toy which is made in many [diverse] parts of the world; i.e. a device no bigger than one's thumb.

From the violence of that salt called saltpetre [together with sulphur and willow charcoal, combined into a powder] so horrible a sound is made by the bursting of a thing so small, no more than a bit of parchment [containing it], that we find [the ear assaulted by a noise] exceeding the roar of strong thunder, and a flash brighter than the most brilliant lightning.

[56] At the beginning of the 20th century, Henry William Lovett Hime of the Royal Artillery published the theory that Bacon's Epistola contained a cryptogram giving a recipe for the gunpowder he witnessed.

[62] Needham et al. concurred with these earlier critics that the additional passage did not originate with Bacon[56] and further showed that the proportions supposedly deciphered (a 7:5:5 ratio of saltpetre to charcoal to sulphur) as not even useful for firecrackers, burning slowly with a great deal of smoke and failing to ignite inside a gun barrel.

[78] Bacon is less interested in a full practical mastery of the other languages than on a theoretical understanding of their grammatical rules, ensuring that a Latin reader will not misunderstand passages' original meaning.

Stillman opined that "there is nothing in it that is characteristic of Roger Bacon's style or ideas, nor that distinguishes it from many unimportant alchemical lucubrations of anonymous writers of the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries", and Muir and Lippmann also considered it a pseudepigraph.

[7] By the early modern period, the English considered him the epitome of a wise and subtle possessor of forbidden knowledge, a Faust-like magician who had tricked the devil and so was able to go to heaven.

[111] A necromantic head was ascribed to Pope Sylvester II as early as the 1120s,[112][n 10] but Browne considered the legend to be a misunderstanding of a passage in Peter the Good's c. 1335 Precious Pearl where the negligent alchemist misses the birth of his creation and loses it forever.

[14] His assertions in the Opus Majus that "theories supplied by reason should be verified by sensory data, aided by instruments, and corroborated by trustworthy witnesses"[119] were (and still are) considered "one of the first important formulations of the scientific method on record".

[146] Lindberg summarised: Bacon was not a modern, out of step with his age, or a harbinger of things to come, but a brilliant, combative, and somewhat eccentric schoolman of the thirteenth century, endeavoring to take advantage of the new learning just becoming available while remaining true to traditional notions... of the importance to be attached to philosophical knowledge".

[147]A recent review of the many visions of Bacon across the ages says contemporary scholarship still neglects one of the most important aspects of his life and thought: his commitment to the Franciscan order.

His Opus majus was a plea for reform addressed to the supreme spiritual head of the Christian faith, written against a background of apocalyptic expectation and informed by the driving concerns of the friars.

[151] To commemorate the 700th anniversary of Bacon's approximate year of birth, Prof. J. Erskine wrote the biographical play A Pageant of the Thirteenth Century, which was performed and published by Columbia University in 1914.