Rogers Commission Report

The report, released and submitted to President Ronald Reagan on June 9, 1986, determined the cause of the disaster that took place 73 seconds after liftoff, and urged NASA to improve and install new safety features on the shuttles and in its organizational handling of future missions.

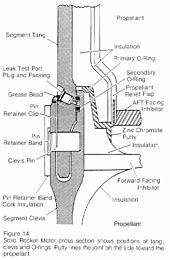

The failure of the O-rings was attributed to a design flaw, as their performance could be too easily compromised by factors including the low temperature on the day of launch.

This was done in large part because of the management structure at NASA and the lack of major checks and balances, which proved to be fatal in this scenario.

His style of investigating with his own direct methods rather than following the commission schedule put him at odds with Rogers, who once commented, "Feynman is becoming a real pain.

"[8] During a televised hearing, Feynman famously demonstrated how the O-rings became less resilient and subject to seal failures at low temperatures by compressing a sample of the material in a clamp and immersing it in a glass of ice water.

These O-rings provided the gas-tight seal needed between the vertically stacked cylindrical sections that made up the solid fuel booster.

[9] Feynman was clearly disturbed by the fact that NASA management not only misunderstood this concept, but inverted it by using a term denoting an extra level of safety to describe a part that was actually defective and unsafe.

Feynman immediately realized that this claim was risible on its face; as he described, this assessment of risk would entail that NASA could expect to launch a shuttle every day for the next 274 years while suffering, on average, only one accident.

[9] Feynman suspected that the 1 in 105 figure was wildly fantastical, and made a rough estimate that the true likelihood of shuttle disaster was closer to 1 in 100.

He was upset NASA presented its fantastical figures as fact to convince a member of the public, schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe, to join the crew.

[9] Feynman's investigation eventually suggested to him that the cause of the Challenger disaster was the very part to which NASA management so mistakenly assigned a safety factor.

Feynman suspected that despite NASA's claims, the O-rings were unsuitable at low temperatures and lost their resilience when cold, thus failing to maintain a tight seal when rocket pressure distorted the structure of the solid fuel booster.

[11] Feynman's investigations also revealed that there had been many serious doubts raised about the O-ring seals by engineers at Morton Thiokol, which made the solid fuel boosters, but communication failures had led to their concerns being ignored by NASA management.

Feynman felt that the Commission's conclusions misrepresented its findings, and he could not in good conscience recommend that such a deeply flawed organization as NASA should continue without a suspension of operations and a major overhaul.

Since 1 part in 100,000 would imply that one could put a Shuttle up each day for 300 years expecting to lose only one, we could properly ask "What is the cause of management's fantastic faith in the machinery?

It would appear that, for whatever purpose, be it for internal or external consumption, the management of NASA exaggerates the reliability of its product, to the point of fantasy.

[20] The unrealistically optimistic launch schedule pursued by NASA had been criticized by the Rogers Commission as a possible contributing cause to the accident.