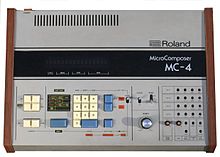

Roland MC-4 Microcomposer

It was released in 1981 with a list price of US$3,295 (equivalent to $11,000 in 2023) (¥430,000 JPY) and was the successor to the MC-8, which in 1977 was the first microprocessor-based digital sequencer.

The MC-4 can be synced to other Roland equipment such as a drum machine or another MC-4 MicroComposer (offering eight separate channels of sequencing).

Below the two advance keys there is another blue button used to tell the MC-4 that you have finished programming a single measure, for example a one bar phrase of notes.

These buttons are used for editing the sequence that has been programmed; they include insert, delete, copy-transpose and repeat.

This gate time refers to the actual sounded value; whether the phrasing is legato, staccato, semi detached etc.

If a sequence is programmed while the MC-4 is set to the default TB, it will never sync correctly to DIN or MIDI clock.

The owners manual shows that a programmed sequence could also be saved to a standard cassette deck.

The Roland MC-4 MicroComposer was able to be used as a stand-alone CV/Gate sequencer, but as the system advanced various additional options were made available for owners needing to use the MC-4 with new tasks and procedures.

These involved things like memory expansion, cassette tape media and synthesizer interfaces.

It was offered as an optional accessory for faster data transfer than a standard audio cassette player.

The whole sound of Chorus is due to the MC-4 not being able to program chords; the limitation of only having four channels of sequencing also contributed.

[18] Clarke was later quoted as saying that he bullied the spares department at Roland UK to supply the micro-cassettes needed for data transfer and later described the MC-4 as being "a pig to program but well worth it".

[19] Before the tour Clarke's collection of MC-4 sequencers were 'road hardened' by having the chips removed from their sockets and soldered directly to the circuit boards.