Catacombs of Rome

Though most famous for Christian burials, either in separate catacombs or mixed together, Jews and also adherents of a variety of pagan Roman religions were buried in catacombs, beginning in the 2nd century AD,[1] occasioned by the ancient Roman ban on burials within a city, and also as a response to overcrowding and shortage of land.

In contrast, the original Roman custom had been cremation of the human body, after which the burnt remains were kept in a pot, urn, or ash-chest, often deposited in a columbarium or dovecote.

[4] From about the 2nd century AD, inhumation (burial of unburnt human remains) became customary, either in graves or, for those who could afford them, in sarcophagi, often elaborately carved.

By the 4th century, burial had overtaken cremation as the usual practice, and the construction of tombs had grown greater and spread throughout the empire.

Considerable tracts of the ancient roads leading out of Rome and other Roman cities, like the Via Appia to this day, had monumental tombs running alongside them.

White says that those catacombs' larger rooms, which had some benches along their walls and were appropriate to hold eucharistic assemblies, were in fact used by Christians to "hol[d] meals for the dead".

These quarries became the basis for later excavation, first by the Romans for rock resources and then by the Christians and Jews for burial sites and mass graves.

[13] After the Edict of Milan in 313, many Roman Christians flocked to the catacombs in order to find relics from the martyrs, and would pillage through the remains.

[12] In the intervening centuries they remained forgotten until they were accidentally rediscovered in 1578, after which Antonio Bosio spent decades exploring and researching them for his Roma Sotterranea (1632).

[6] Responsibility for the Christian catacombs lies with the Holy See, which has set up active official organizations for this purpose: the Pontifical Commission of Sacred Archaeology (Pontificia Commissione di Archeologia Sacra) directs excavations and restoration works, while the study of the catacombs is directed in particular by the Pontifical Academy of Archaeology.

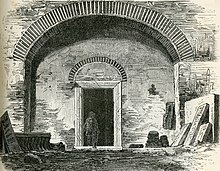

Another type of burial, typical of Roman catacombs, was the arcosolium, consisting of a curved niche, enclosed under a carved horizontal marble slab.

Cubicula (burial rooms containing loculi all for one family) and cryptae (chapels decorated with frescoes) are also commonly found in catacomb passages.

These catacombs are situated on the ancient Via Labicana, today Via Casilina in Rome, Italy, near the church of Santi Marcellino e Pietro ad Duas Lauros.

In the beginning of 2009,[15] at the request of the Vatican, the Divine Word Missionaries, a Roman Catholic Society of priests and Brothers, assumed responsibility as an administrator of St. Domitilla Catacombs.

Located on the Campana Road, these catacombs are said to have been the resting place, perhaps temporarily, of Simplicius, Faustinus and Beatrix, Christian Martyrs who died in Rome during the Diocletian persecution (302 or 303).

In the oldest parts of the complex may be found the "cubiculum of the coronation", with a rare depiction for that period of Christ being crowned with thorns, and a 4th-century painting of Susanna and the old men in the allegorical guise of a lamb and wolves.

[4] Sited along the Appian way, these catacombs were built after 150 AD, with some private Christian hypogea and a funereal area directly dependent on the Catholic Church.

The arcades, where more than fifty martyrs and sixteen popes were buried, form part of a cemetery complex that occupies fifteen hectares.

The Catacombs of San Callisto are around 90 acres large, 12 miles long and contain four levels, extending to a depth of more than 20 meters underground.

Built into the hill beside San Lorenzo fuori le Mura, these catacombs are said to have been the final resting place of St. Lawrence.

[18] Established underneath the San Pacrazio basilica which was built by Pope Symmachus on the place where the body of the young martyr Saint Pancras, or Pancratius, had been buried.

On the left-hand end of the right-hand wall of the nave of the primitive basilica, rebuilt in 1933 on ancient remains, arches to end the middle of the nave of the actual church, built in the 13th century, are visible, along with the outside of the apse of the Chapel of the Relics; whole and fragmentary collected sarcophagi (mostly of 4th-century date) were found in excavations.

[19] Via a staircase down, one finds the arcades where varied cubicula (including the cubiculum of Giona's fine four stage cycle of paintings, dating to the end of the 4th century).

One then arrives at the restored crypt of S. Sebastiano, with a table altar on the site of the ancient one (some remains of the original's base still survive) and a bust of Saint Sebastian attributed to Bernini.

On the left is the mausoleum of Ascia, with an exterior wall painting of vine shoots rising from kantharoi up trompe-l'œil pillars.

From the "Trigilia" one passed into an ancient ambulatory, which turns around into an apse: here is a collection of epitaphs and a model of all the mausolei, of the "Triglia" and of the Constantinian basilica.

From here one descends into the "Platonica", construction at the rear of the basilica that was long believed to have been the temporary resting place for Peter and Paul, but was in fact (as proved by excavation) a tomb for the martyr Quirinus, bishop of Sescia in Pannonia, whose remains were brought here in the 5th century.

To the right of the "Platonica" is the chapel of Honorius III, adapted as the vestibule of the mausoleum, with interesting 13th-century paintings of Peter and Paul, the Crucifixion, saints, the Massacre of the Innocents, Madonna and Child, and other subjects.

Agnes' bones are now conserved in the church of Sant'Agnese fuori le mura in Rome, built over the catacomb.

Most artworks are religious in nature, some depicting important Christian rites such as baptism, or scenes and stories such as the tale of "The Three Hebrews and the Fiery Furnace," or biblical figures such as Adam and Eve.