Roman Catholic Diocese of Oloron

The former Roman Catholic Diocese of Oloron was a Latin rite bishopric in Pyrénées-Atlantiques department, Aquitaine region of south-west France, from the 6th to the 19th century.

For administrative purposes the diocese was subdivided (by the thirteenth century) into six archdeaconries, those of Oleron, Soule, Navarrenx, Garenz, Aspe, and Lasseube.

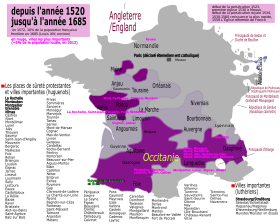

[2] The archdeaconries and archpriesthoods disappeared in the sixteenth century, when Béarn was protestantized by the official policy of the royal house of Navarre, especially by Jeanne d'Albret.

The Bishop and Chapter were jointly seigneurs of the town of Sainte-Marie, on the opposite bank of the river Gave from Oloron, where the episcopal palace was located.

– 1089), who had been a Benedictine monk, presided as Legate of Pope Gregory VII in a Council held at Poitiers on 26 May 1075, to deal with the marital irregularities of Count Guillaume of Poitou.

They immediately notified Pope Innocent IV, who was staying at Lyon at that time, and drew his attention to the Elect's sterling qualities, but also to the fact that the bishop-elect was not eligible for the office super natalium defectu (illegitimacy).

On 14 July 1246 Pope Innocent provided the necessary dispensation and the mandate to the Archbishop to consecrate Pierre de Gavarret as Bishop of Oloron.

One of the clergy of Oloron, Arnaldus Guillelmi de Mirateug, went in person to Auch, armed with documents and petitions, intending to persuade the archbishop not to ratify the election.

Arnaldus, however, pursued the archbishop, and eventually got an interview; he presented his criminal charges, and to prevent the confirmation of the election, he appealed to the Pope.

The entire affair was reported at a papal audience by Garsias Arnaldi, lord of Novaliis, who laid charges of simony, homicide, perjury, public money-lending, and living in concubinage.

Pope Clement, who wished to know the truth of the dispute, sent a mandate on 10 August 1308 to the Bishop of Tarbes (Gerold Doucet), whom he trusted, to make a thorough investigation of the affair, and if he were to find anything amiss, to cite the Bishop-elect, Guillaume Arnaudi, to the Papal Court, and give him three months to appear personally.

He appears as confirmatus et electus in a charter of Count Gaston de Foix, dated the Wednesday after the Feast of Notre-Dame (8 September) 1308.

These allowed only one synod a year, at the call of the Lieutenant General of the realm (who, at the time, was the Bishop of Oleron, Claude Régin).

Protestant ministers were permitted to preach and pray in any place in the kingdom, and Catholic clergy were forbidden to interfere in such sermons and prayers.

Benefices were to be suppressed on the death or resignation of the incumbent, and the money applied to poor relief of members of the Reformed Church.

"We [Seneschals and Lieutenants General], following the will of God and of the aforesaid Lady [Jeanne d'Albret]... have annulled, expelled, and banned from this land every exercise of the Roman religion without any exception, such as masses, processions.

At Oleron, two priests were massacred by Huguenot mobs, and half of the monks and nuns fled to Spain while the rest were killed.

The new Civil Constitution mandated that bishops be elected by the citizens of each 'département',[23] which immediately raised the most severe issues in Canon Law, since the electors did not need to be Catholics and the approval of the Pope was not only not required, but actually forbidden.

He declined to take the required oath to the Civil Constitution, and instead wrote a monitory letter to the clergy of his diocese on 22 February 1791, encouraging them to resist.

From the point of view of Canon Law, it was Pope Pius VII's bull Qui Christi Domini of 29 November 1801,[27] which reestablished the dioceses of France, that did not restore Oleron.

[28] The episcopal see of the bishops of Oloron was in the Cathédrale Sainte-Marie, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, in Oloron-Sainte-Marie, in the department of Pyrénées-Atlantiques.

[33] His successor, Jean-Baptiste-Auguste de Villoutreix, continued the policy, and appointed a new principal, Barthelelmy Bover, who was a doctor of the Sorbonne.