Roman navy

In the course of the first half of the 2nd century BC, Rome went on to destroy Carthage and subdue the Hellenistic kingdoms of the eastern Mediterranean, achieving complete mastery of the inland sea, which they called Mare Nostrum.

One of them, the Vandal Kingdom with its capital at Carthage, raised a navy of its own and raided the shores of the Mediterranean, even sacking Rome, while the diminished Roman fleets were incapable of offering any resistance.

[4][6] However, the Republic continued to rely mostly on her legions for expansion in Italy; the navy was most likely geared towards combating piracy and lacked experience in naval warfare, being easily defeated in 282 BC by the Tarentines.

[6][7][8] This situation continued until the First Punic War: the main task of the Roman fleet was patrolling along the Italian coast and rivers, protecting seaborne trade from piracy.

In the last battle of the war, at Aegates Islands in 241 BC, the Romans under Gaius Lutatius Catulus displayed superior seamanship to the Carthaginians, notably using their rams rather than the now-abandoned Corvus to achieve victory.

[15] This ensured Carthaginian acquiescence to the conquest of Sardinia and Corsica, and also enabled Rome to deal decisively with the threat posed by the Illyrian pirates in the Adriatic.

[16] Initially, in 229 BC, a fleet of 200 warships was sent against Queen Teuta, and swiftly expelled the Illyrian garrisons from the Greek coastal cities of modern-day Albania.

Due to Rome's command of the seas, Hannibal, Carthage's great general, was forced to eschew a sea-borne invasion, instead choosing to bring the war over land to the Italian peninsula.

In view of the massive Roman naval superiority, the war was fought on land, with the Macedonian fleet, already weakened at Chios, not daring to venture out of its anchorage at Demetrias.

These victories, which were invariably concluded with the imposition of peace treaties that prohibited the maintenance of anything but token naval forces, spelled the disappearance of the Hellenistic royal navies, leaving Rome and her allies unchallenged at sea.

Coupled with the final destruction of Carthage, and the end of Macedon's independence, by the latter half of the 2nd century BC, Roman control over all of what was later to be dubbed mare nostrum ("our sea") had been established.

[25] In the absence of a strong naval presence however, piracy flourished throughout the Mediterranean, especially in Cilicia, but also in Crete and other places, further reinforced by money and warships supplied by King Mithridates VI of Pontus, who hoped to enlist their aid in his wars against Rome.

Perhaps most important of all, the pirates disrupted Rome's vital lifeline, namely the massive shipments of grain and other produce from Africa and Egypt that were needed to sustain the city's population.

[35] In the event, when the two fleets encountered each other in Quiberon Bay, Caesar's navy, under the command of D. Brutus, resorted to the use of hooks on long poles, which cut the halyards supporting the Veneti sails.

In the East, the Republican faction quickly established its control, and Rhodes, the last independent maritime power in the Aegean, was subdued by Gaius Cassius Longinus in 43 BC, after its fleet was defeated off Kos.

In the years 15 and 16, Germanicus carried out several fleet operations along the rivers Rhine and Ems, without permanent results due to grim Germanic resistance and a disastrous storm.

Civilis attempted only a short encounter with his own fleet, but could not hinder the superior Roman force from landing and ravaging the island of the Batavians, leading to the negotiation of a peace soon after.

[53] There is some speculation about a Roman landing in Ireland, based on Tacitus reports about Agricola contemplating the island's conquest,[54] but no conclusive evidence to support this theory has been found.

Under the aegis of the Severan dynasty, the only known military operations of the navy were carried out under Septimius Severus, using naval assistance on his campaigns along the Euphrates and Tigris, as well as in Scotland.

Via two surprise attacks (256) on Roman naval bases in the Caucasus and near the Danube, numerous ships fell into the hands of the Germans, whereupon the raids were extended as far as the Aegean Sea; Byzantium, Athens, Sparta and other towns were plundered and the responsible provincial fleets were heavily debilitated.

[63] With a single blow Roman control of the channel and the North Sea was lost, and emperor Maximinus was forced to create a completely new Northern Fleet, but in lack of training it was almost immediately destroyed in a storm.

Although Emperor Diocletian is held to have strengthened the navy, and increased its manpower from 46,000 to 64,000 men,[67] the old standing fleets had all but vanished, and in the civil wars that ended the Tetrarchy, the opposing sides had to mobilize the resources and commandeered the ships of the Eastern Mediterranean port cities.

[71] In Imperial times, non-citizen freeborn provincials (peregrini), chiefly from nations with a maritime background such as Greeks, Phoenicians, Syrians and Egyptians, formed the bulk of the fleets' crews.

Crewmen could sign on as marines, rowers/seamen, craftsmen and various other jobs, though all personnel serving in the imperial fleet were classed as milites ("soldiers"), regardless of their function; only when differentiation with the army was required were the adjectives classiarius or classicus added.

[78][85] Nevertheless, the prefects remained largely political appointees, and despite their military experience, usually in command of army auxiliary units, their knowledge of naval matters was minimal, forcing them to rely on their professional subordinates.

The tasks at hand for the Roman navy were now the policing of the Mediterranean waterways and the border rivers, suppression of piracy, and escort duties for the grain shipments to Rome and for imperial army expeditions.

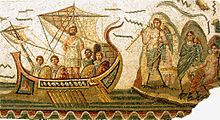

[25] Roman ships were commonly named after gods (Mars, Iuppiter, Minerva, Isis), mythological heroes (Hercules), geographical maritime features such as Rhenus or Oceanus, concepts such as Harmony, Peace, Loyalty, Victory (Concordia, Pax, Fides, Victoria) or after important events (Dacicus for the Trajan's Dacian Wars or Salamina for the Battle of Salamis).

This had several advantages: the heavier and sturdier construction lessened the effects of ramming, and the greater space and stability of the vessels allowed the transport not only of more marines, but also the placement of deck-mounted ballistae and catapults.

Although it brought them some decisive victories, it was discontinued because it tended to unbalance the quinqueremes in high seas; two Roman fleets are recorded to have been lost during storms in the First Punic War.

A large part of the fleet of Mark Antony was burned, and the rest was withdrawn to a new base at Forum Iulii (modern Fréjus),[103] which remained operative until the reign of Claudius.