Roman diocese

The term diocese comes from the Latin: dioecēsis, which derives from the Ancient Greek: dioíkēsis (διοίκησις) meaning "administration", "management", "assize district", or "group of provinces".

Egypt lost its unique status and was divided into three provinces,[3] while Italia was 'provincialized' - the numbered regiones established by Augustus received names and were governed by correctores.

[10][11] A passage of Lactantius, who was hostile to Diocletian because of his persecution of the Christians, seems to indicate the existence of vicarii praefectorum in the time of Diocletian: And so that everything would be filled with terror, the provinces were also sliced to bits; many governors and more offices brooded over individual regions and almost every city, as well as many rationales, magistri, and vicarii praefectorum, all of whose civil acts were exceedingly rare, but whose condemnations and proscriptions were common, whose exactions of innumerable taxes were not so much frequent as constant, and the damage from these taxes was unbearable.Thus Lactantius refers to the vicarii praefectorum as being active already in Diocletian's time.

Other sources from Diocletian's reign mention one Aurelius Agricolanus who was an agens vices praefectorum praetorio active in Hispania and condemned a centurion named Marcellus to be executed for his Christianity, as well as an Aemilianus Rusticianus, who is considered by some scholars to have been the first vicar of the Diocese of the East that we know of.

According to Zuckerman, the establishment of the dioceses should instead be dated to around AD 313/14, after the annexation of Armenia into the Roman empire and the meeting of Constantine and Licinius in Mediolanum.

Hitherto, one or two Praetorian prefects had served as chief minister for the whole empire, with military, judicial, and fiscal responsibilities.

Around the end of the 5th century, the majority of the dioceses of the Western Roman Empire ceased to exist, following the establishment of the Barbarian kingdoms.

When Theoderic conquered Provence in 508, he also re-established a Diocese of the Gauls, which was promoted to the rank of Prefecture with a capital at Arelate two years later.

The civilian offices, including the vicars, praesides, and Praetorian Prefects, continued to be filled with Roman citizens, while Barbarians without citizenship were barred from holding them.

According to Cassiodorus, however, the authority of the vicarius urbis Romae was diminished: in the 4th century, he no longer controlled the ten provinces of Italia Suburbicaria, but only the land within forty miles of the City of Rome.

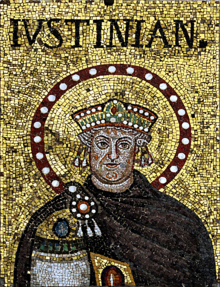

[20] In 535–536, Justinian decided to abolish the dioceses of the East, Asia, and Pontus; their vicars were demoted to simple provincial governors.

This prefecture contained the provinces of Moesia II, Scythia Minor, Insulae (the Cyclades), Caria, and Cyprus.

[23][24] In 539, Justinian also abolished the diocese of Egypt, splitting it into five independent circumscriptions (groups of provinces) governed by duces with civilian and military authority, who were direct subordinates of the Praetorian prefect of the East.

[26] Morevoer, by abolishing the dioceses, Justinian attempted to simplify the bureaucracy and simultaneously decrease the state's expenses, noting that the vicars had become superfluous, since their courts of appeal were used ever less frequently and the provincial governors could be directly controlled by the Praetorian Prefect, by means of the so-called tractatores.

In fact, thirteen years after the reforms of 535, in 548, Justinian decided to re-establish the diocese of Pontus due to serious internal problems.

The vicars and other civilian officials seem to have lost most of their importance to the exarchs and their subordinates, but did not disappear until the middle of the 7th century AD.

The last certain attestation of a Praetorian Prefect of the East is in 629, while Illyricum survived to the end of the 7th century, but without any effective power since the majority of the Balkans, aside from Thessaloniki, had fallen under the Slavs.

[30] If the dioceses lost their fiscal functions during the 6th and 7th centuries, it may be that they were replaced by new groupings of provinces under the judicial administration of a Proconsul (anthypatos).

René Rémond suggests that this paradox was resolved by promoting vicars whose dioceses contained provinces with senatorial governors to the rank of clarissimus, but there is no evidence for this.

[35] Initially, the powers of the vicars were considerable: they controlled and monitored the governors (aside from the proconsuls who governed Asia and Africa), administered the collection of taxes, intervened in military affairs in order to fortify the borders, and judged appeals.

[18] In as much as they were responsible for the integrity of the global diocesan budgets drawn up by the prefectures, they were in 328–329 AD given oversight powers and appeal authority over the Treasury and Crown Estate officials but could not meddle in their routine business.

The position went into decline from the first decades of the 5th century as the emperors switched back to the two tier prefect-governor arrangement rather than the 3 level with the diocese as regional level as fiscal officials for central headquarters became stationed in the provinces and the change over to the great bulk of tax collection in gold simplified the amount of paperwork and transport needs.

[36] The vicars had no real military role and had no troops under their command, which was a significant novelty compared to the Augustan provincial system.