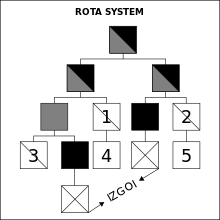

Rota system

[1] "Whether there was a system of succession in the early Rus' principalities and, to the extent there was one, its operation as well as how long it lasted, has been in dispute among historians."

[2] Proponents of the rota system usually attribute its introduction or rationalisation to Yaroslav the Wise (died 1054), who assigned each of his sons a principality based on seniority.

[4] Proponents of the rota system have included Sergei Soloviev, Vasily Klyuchevsky,[1] Mykhailo Hrushevsky,[2] Mikhail Borisovich Sverdlov, and George Vernadsky.

Some scholars have argued that a rota system did exist, but failed to function properly, with John Lister Illingworth Fennell theorising that as the princely clan grew larger and larger, an increasing number of junior princes was excluded from the right to succeed, and driven as they were by greed, they were the ones starting all the succession struggles.

[5] On the other hand, Nancy Shields Kollmann sought to demonstrate that dynastic growth rarely led to instability, as high rates of mortality and the exclusion of izgoi branches kept the number of eligible princes "manageable";[5] a hypothesis that Janet L. B. Martin seconded.

Indeed, scholars such as Sergeevich and Budovnitz argued that the seemingly endless internecine war among the princes of Kiev indicates a total lack of any established succession system.

Shemyaka's father, Yury of Zvenigorod, claimed that he was the rightful heir to the throne of the Principality of Vladimir through collateral succession.

- Grey: incumbent

- Half-grey: predecessor of incumbent

- Square: male

- Black: deceased

- Diagonal: cannot be displaced

- cross: excluded or Izgoi (excluded from succession due to their parent never having held the throne)