Thomas Chatterton

He was able to pass off his work as that of an imaginary 15th-century poet called Thomas Rowley, chiefly because few people at the time were familiar with medieval poetry, though he was denounced by Horace Walpole.

At 17, he sought outlets for his political writings in London, having impressed the Lord Mayor, William Beckford, and the radical leader John Wilkes, but his earnings were not enough to keep him, and he poisoned himself in despair.

His unusual life and death attracted much interest among the romantic poets, and Alfred de Vigny wrote a play about him that is still performed today.

[3] After Chatterton's birth (15 weeks after his father's death on 7 August 1752),[1] his mother established a girls' school and took in sewing and ornamental needlework.

Then he found a fresh interest in oaken chests in the muniment room over the porch on the north side of the nave, where parchment deeds, old as the Wars of the Roses, lay forgotten.

His lonely circumstances helped foster his natural reserve, and to create the love of mystery which exercised such an influence on the development of his poetry.

He also liked to lock himself in a little attic which he had appropriated as his study; and there, with books, cherished parchments, loot purloined from the muniment room of St Mary Redcliffe, and drawing materials, the child lived in thought with his 15th-century heroes and heroines.

[3] The first of his literary mysteries was the dialogue of "Elinoure and Juga," which he showed to Thomas Phillips, the usher at Colston's Hospital (where he was a pupil), pretending it was the work of a 15th-century poet.

[5] Chatterton's "Rowleian" jargon appears to have been chiefly the result of the study of John Kersey's Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum, and it seems his knowledge even of Chaucer was very slight.

The antiquary William Barrett relied exclusively on these fake transcripts when writing his History and Antiquities of Bristol (1789) which became an enormous failure.

Imitating the style of the pseudonymous letter writer Junius, then in the full blaze of his triumph, he turned his pen against the Duke of Grafton, the Earl of Bute and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha (the then Princess of Wales).

[16] He had just dispatched one of his political diatribes to the Middlesex Journal when he sat down on Easter Eve, 17 April 1770, and penned his "Last Will and Testament," a satirical compound of jest and earnest, in which he intimated his intention of ending his life the following evening.

John Lambert, the attorney to whom he was apprenticed, cancelled his indentures; his friends and acquaintances having donated money, Chatterton went to London.

He could assume the style of Junius or Tobias Smollett, reproduce the satiric bitterness of Charles Churchill, parody James Macpherson's Ossian, or write in the manner of Alexander Pope or with the polished grace of Thomas Gray and William Collins.

The note of his actual receipts, found in his pocket-book after his death, shows that Hamilton, Fell and other editors who had been so liberal in flattery, had paid him at the rate of a shilling for an article, and less than eightpence each for his songs; much of the accepted material was held in reserve and still unpaid for.

[16] In August 1770, while walking in St Pancras Churchyard, Chatterton was much absorbed in thought, and did not notice a newly dug open grave in his path, and tumbled into it.

On observing this event, his walking companion helped Chatterton out of the grave, and told him in a jocular manner that he was happy in assisting at the resurrection of genius.

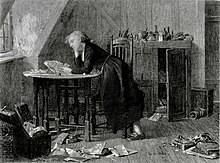

[22] On 24 August 1770, he retired for the last time to his attic in Brook Street, carrying with him arsenic,[23] which he drank after tearing into fragments whatever literary remains were at hand.

[25] A few days later, one Dr Thomas Fry came to London with the intention of giving financial support to the young boy "whether discoverer or author merely.

"[26] A fragment, probably one of the last pieces written by the poet, was put together by Dr Fry from the shreds of paper that covered the floor of Chatterton's attic on the morning of 25 August 1770.

[27] This fragment, possibly one of the remnants of Chatterton's very last literary efforts, was identified by Dr Fry to be a modified ending of the poet's tragical interlude Aella.

[31][32] The death of Chatterton attracted little notice at the time; for the few who then entertained any appreciative estimate of the Rowley poems regarded him as their mere transcriber.

He was interred in a burying-ground attached to the Shoe Lane Workhouse in the parish of St Andrew, Holborn, later the site of Farringdon Market.

This was reprinted in the edition (1803) of Chatterton's Works by Robert Southey and Joseph Cottle, published for the benefit of the poet's sister.

It has long been agreed that Chatterton was solely responsible for the Rowley poems; the language and style were analysed in confirmation of this view by W. W. Skeat in an introductory essay prefaced to vol.

Herbert Croft, in his Love and Madness, interpolated a long and valuable account of Chatterton, giving many of the poet's letters, and much information obtained from his family and friends (pp.

[40] There is a collection of "Chattertoniana" in the British Library, consisting of works by Chatterton, newspaper cuttings, articles dealing with the Rowley controversy and other subjects, with manuscript notes by Joseph Haslewood, and several autograph letters.

[34] E. H. W. Meyerstein, who worked for many years in the manuscript room of the British Museum wrote a definitive work—"A Life of Thomas Chatterton"—in 1930.

[41] Peter Ackroyd's 1987 novel Chatterton was a literary re-telling of the poet's story, giving emphasis to the philosophical and spiritual implications of forgery.

[citation needed] In 1886, architect Herbert Horne and Oscar Wilde unsuccessfully attempted to have a plaque erected at Colston's School, Bristol.