Royal forest

A royal forest, occasionally known as a kingswood (Latin: silva regis),[1][2] is an area of land with different definitions in England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

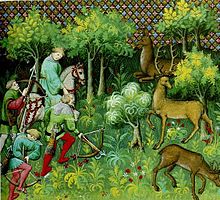

The term forest in the ordinary modern understanding refers to an area of wooded land; however, the original medieval sense was closer to the modern idea of a "preserve" – i.e. land legally set aside for specific purposes such as royal hunting – with less emphasis on its composition.

[3] In Anglo-Saxon England, though the kings were great huntsmen, they never set aside areas declared to be "outside" (Latin foris) the law of the land.

[4] Afforestation, in particular the creation of the New Forest, figured large in the folk history of the "Norman yoke", which magnified what was already a grave social ill: "the picture of prosperous settlements disrupted, houses burned, peasants evicted, all to serve the pleasure of the foreign tyrant, is a familiar element in the English national story ....

Royal forests usually included large areas of heath, grassland and wetland – anywhere that supported deer and other game.

This could foster resentment as the local inhabitants were then restricted in the use of land they had previously relied upon for their livelihoods; however, common rights were not extinguished, but merely curtailed.

This operated outside the common law, and served to protect game animals and their forest habitat from destruction.

In the year of his death, 1087, a poem, "The Rime of King William", inserted in the Peterborough Chronicle, expresses English indignation at the forest laws.

The five animals of the forest protected by law were given by Manwood as the hart and hind (i.e. male and female red deer), boar, hare and wolf.

The rights of chase and of warren (i.e. to hunt such beasts) were often granted to local nobility for a fee, but were a separate concept.

The nomenclature of the officers can be somewhat confusing: the rank immediately below the constable was referred to as foresters-in-fee, or, later, woodwards, who held land in the forest in exchange for rent, and advised the warden.

Another group, called serjeants-in-fee, and later, foresters-in-fee (not to be confused with the above), held small estates in return for their service in patrolling the forest and apprehending offenders.

These last reported to the court of justice-seat and investigated encroachments on the forest and invasion of royal rights, such as assarting.

While their visits were infrequent, due to the interval of time between courts, they provided a check against collusion between the foresters and local offenders.

Blackstone gives the following outline of the forest courts, as theoretically constructed: In practice, these fine distinctions were not always observed.

The courts of justice-seat crept into disuse, and in 1817, the office of justice in eyre was abolished and its powers transferred to the First Commissioner of Woods and Forests.

Since the conquest of England, the forest, chase and warren lands had been exempted from the common law and subject only to the authority of the king, but these customs had faded into obscurity by the time of The Restoration.

William Rufus, also a keen hunter, increased the severity of the penalties for various offences to include death and mutilation.

Magna Carta, the charter forced upon King John of England by the English barons in 1215, contained five clauses relating to royal forests.

James I and his ministers Robert Cecil and Lionel Cranfield pursued a policy of increasing revenues from the forests and starting the process of disafforestation.

[20] Cecil made the first steps towards abolition of the forests, as part of James I's policy of increasing his income independently of Parliament.

Cranfield's work led directly to the disafforestation of Gillingham Forest in Dorset and Chippenham and Blackmore in Wiltshire.

A legal action by the Attorney General would then proceed in the Court of Exchequer against the forest residents for intrusion, which would confirm the settlement negotiated by the commission.

Crown lands would then be granted (leased), usually to prominent courtiers, and often the same figures that had undertaken the commission surveys.

[21] The disafforestations caused riots and Skimmington processions resulting in the destruction of enclosures and reoccupation of grazing lands in a number of West Country forests, including Gillingham, Braydon and Dean, known as the Western Rising.

The riots followed the physical enclosure of lands previously used as commons, and frequently led to the destruction of fencing and hedges.

The rioters in Dean fully destroyed the enclosures surrounding 3,000 acres in groups that numbered thousands of participants.

1. c. 16, also known as Selden's Act) to revert the forest boundaries to the positions they had held at the end of the reign of James I.

The core of the forest[citation needed] is the Special Area of Conservation named Birklands and Bilhaugh.

[28] It is a remnant of an older, much larger, royal hunting forest, which derived its name from its status as the shire (or sher) wood of Nottinghamshire, which extended into several neighbouring counties (shires), bordered on the west along the River Erewash and the Forest of East Derbyshire.