Royal Irish Constabulary

[1] For most of its history, the ethnic and religious makeup of the RIC broadly matched that of the Irish population, although Anglo-Irish Protestants were overrepresented among its senior officers.

Unlike police elsewhere in the United Kingdom, RIC constables were routinely armed (including with carbines) and billeted in barracks, and the force had a militaristic structure.

A force of 400 armed policemen and 40 mounted petty constables, all full-time and uniformed, headed by three commissioners, four divisional judges and two clerks, was viewed as oppressive by local elites and became a strain on the city budget.

That arguably excessive budget was used as a pretext by Irish nationalist MP Henry Grattan and short-lived Lord Lieutenant of Ireland William Fitzwilliam, 4th Earl Fitzwilliam, to essentially abolish the Dublin Police in 1795 (even despite some success with fighting the crime), downsizing it to two inspectors and 50 constables headed by superintendend magistrate and two divisional justices and even temporarily moving it under Dublin Corporation.

The police faced civil unrest among the Irish rural poor, and was involved in bloody confrontations during the period of the Tithe War.

The new constabulary first demonstrated its efficiency against civil agitation and Irish separatism during Daniel O'Connell's 1843 "monster meetings" to urge repeal of the Act of Parliamentary Union, and the Young Ireland campaign led by William Smith O'Brien in 1848, although it failed to contain violence at the so-called "Battle of Dolly's Brae" in 1849 (which provoked a Party Processions Act to regulate sectarian demonstrations).

The success of the Irish Constabulary during the outbreak was rewarded by Queen Victoria who granted the force the prefix 'Royal' in 1867[1] and the right to use the insignia of the Most Illustrious Order of St Patrick in their motif.

The unstable rural unrest of the early nineteenth century characterised by secret organisations and unlawful armed assembly was effectively controlled.

About 70% of the police force in Belfast declared their support of the strikers and were encouraged by Larkin to carry out their own strike for higher wages and a better pension.

The RIC's existence was increasingly troubled by the rise of the Home Rule campaign[10] in the early twentieth century period prior to World War I.

His years in the RIC coincided with the rise of a number of political, cultural and sporting organisations with the common aim of asserting Ireland's separateness from England.

[12] However, in April 1916 when Nathan showed him a letter from the army commander in the south of Ireland telling of an expected landing of arms on the southwest coast and a rising planned for Easter, they were both 'doubtful whether there was any foundation for the rumour'.

Although the Royal Commission on the 1916 Rebellion cleared the RIC of any blame for the Rising, Chamberlain had already resigned his post, along with Birrell and Nathan.

To some extent it had a quasi-military or gendarmerie ethos: barracks and carbines; a marked class distinction between officers and men; jurisdiction over rural districts lacking a population density to warrant their own civilian police force; obligatory service outside of one's region of origin; plus a dark green uniform with black buttons and insignia, resembling that of the rifle regiments of the British Army.

A delegation of prominent Irish-Americans led by former Illinois governor Edward F. Dunne, returned with the following impression:"The Constabulary is a branch of the Military forces.

[17] [20] Enforcement of eviction orders in rural Ireland caused the RIC to be widely distrusted by the poor Catholic population as the mid 19th century approached, but the relative calm of the late Victorian and Edwardian periods brought it increasing, if grudging, respect.

In rural areas their attention was largely on minor problems such as distilling, cockfighting, drunk and disorderly behaviour, and unlicensed dogs or firearms, with only occasional attendance at evictions or on riot duty; and arrests tended to be relatively rare events.

While "barracks" in cities resembled those of the British Army, the term was also used for small country police stations consisting of a couple of ordinary houses with a day-room and a few bedrooms; premises would be rented by the authorities from landowners and might be changed between different sites in a village.

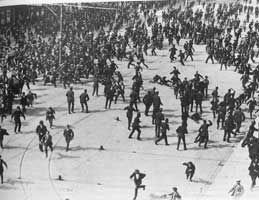

On 31 August 1913 at 1.30pm the DMP and RIC rioted in O'Connell Street, attacking what they thought was a crowd come to hear the Trade unionist Jim Larkin speak.

[33] The Irish Republican Army under the leadership of Michael Collins began systematic attacks on British government forces.

To reinforce the much reduced and demoralised police the United Kingdom government recruited returned World War I veterans from English and Scottish cities.

They were sent to Ireland in 1920, to form a police reserve unit which became known as the "Black and Tans" and the Auxiliary Division of the Royal Irish Constabulary.

[36] Some regular RIC men resigned in protest at the often brutal and undisciplined behaviour of the new recruits; others suffered crises of conscience which troubled them for the rest of their lives.

[37] In February 1921 the British Prime Minister Lloyd George notified Hamar Greenwood (the Chief Secretary for Ireland) that he was "not at all satisfied with the discipline of the Royal Irish Constabulary and its auxiliary force.

[39] The RIC was replaced by the Civic Guard (renamed as the Garda Síochána the following year) in the Irish Free State and by the Royal Ulster Constabulary in Northern Ireland.

Others, still faced with threats of violent reprisals,[43] emigrated with their families to Great Britain or other parts of the Empire, most often to join police forces in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Southern Rhodesia.