RSPCA

The emergence of the RSPCA has its roots in the intellectual climate of the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Britain where opposing views were exchanged in print concerning the use of animals.

The harsh use and maltreatment of animals in hauling carriages, scientific experiments (including vivisection), and cultural amusements of fox-hunting, bull-baiting and cock fighting were among some of the matters that were debated by social reformers, clergy, and parliamentarians.

[5] At the beginning of the 19th century there was an unsuccessful attempt by Sir William Pulteney on 18 April 1800 to pass legislation through the British parliament to ban the practice of bull-baiting.

[7] Erskine in his parliamentary speech combined the vocabulary of animal rights and trusteeship with a theological appeal to biblical passages opposing cruelty.

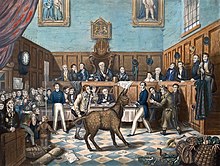

[9] Martin's Act was supported by various social reformers who were not parliamentarians, and the efforts of the Reverend Arthur Broome (1779–1837) to create a voluntary organisation to promote kindness toward animals resulted in the founding of an informal network.

Among the others who were present as founding members were Sir James Mackintosh MP, Richard Martin, William Wilberforce, Basil Montagu, John Ashley Warre, the Rev.

[17] The origins of the role of the RSPCA inspector stem from Broome's efforts in 1822 to personally bring to court some individuals against whom charges of cruelty were heard.

[21] Broome's experience of bankruptcy and prison created difficulties for him afterwards and he stood aside as the society's first secretary in 1828 and was succeeded by the co-founding member Lewis Gompertz.

[30] The RSPCA also had annual accounts published in newspapers, like The Londoner, where the secretary would discuss improvements, report cases, and remind the public to watch over their animals' health.

The terms of the competition stipulated:"The Essay required is one which shall morally illustrate, and religiously enforce, the obligation of man towards the inferior and dependent creatures – their protection and security from abuse, more especially as regards those engaged in service, and for the use and benefit of mankind-on the sin of cruelty – the infliction of wanton or unnecessary pain, taking the subject under its various denominations – exposing the specious defence of vivisection on the ground of its being for the interests of science – the supplying the infinite demands on the poor animal in aid of human speculations by exacting extreme labour, and thereby causing excessive suffering – humanity to the brute as harmonious with the spirit and doctrines of Christianity, and the duty of man as a rational and accountable creature.

At the society's first annual meeting in 1825, which was held at the Crown and Anchor Tavern on 29 June 1825, the public notice that announced the gathering specifically included appropriate accommodation for the presence of women members.

[39] In 1839 another female supporter of the society, Sarah Burdett, a relative of the philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts and a poet, published her theological understanding of the rights of animals.

[43] In the 19th century the RSPCA fostered international relations on the problem of cruelty through the sponsoring of conferences and in providing basic advice on the establishment of similar welfare bodies in North America and in the colonies of the British Empire.

There was a public groundswell of opinions that were divided into opposing factions concerning vivisection, where Charles Darwin (1809–1882) campaigned on behalf of scientists to conduct experiments on animals while others, such as Frances Power Cobbe (1822–1904) formed an anti-vivisection lobby.

[48] This qualified support for experiments on animals was at odds with the stance taken by Society's founder Broome who had in 1825 sought medical opinions about vivisection and he published their anti-vivisection sentiments.

[50][51] During the First World War the RSPCA provided support for the Army Veterinary Corps in treating animals such as donkeys, horses, dogs and birds that were co-opted into military service as beasts of burden, messengers and so forth.

[55] Since the end of the Second World War the development of intense agricultural farming practices has raised many questions for public debate concerning animal welfare legislation and the role of the RSPCA.

[68] In previous years the National Headquarters located at Southwater in West Sussex houses several general departments, each with a departmental head, consistent with the needs of any major organisation.

[69] Since the pandemic the RSPCA no longer has a National Headquarters, with most employees now working from home and small satellite offices being set up in locations such as Horsham and London.

Although RSPCA workers do not have direct access to the PNC, information is shared with them by the various police constabularies which would reveal any convictions, cautions, warnings, reprimands and impending prosecutions.

The Association of Chief Police Officers released a statement clarifying that the RSPCA had no direct access to the PNC, and that in common with other prosecuting bodies, it may make a request for disclosure of records.

[81] In 1925, Ada Cole and Jules Ruhl produced a controversial film for the RSPCA depicting the inhumane slaughter of export horses in Belgium that featured graphic footage taken at the village of Terhagon in 1914.

[84][85] In October 1925, the Departmental Committee of the Ministry of Agriculture published a report which concluded that the footage showing horses being stabbed to death was staged and filmed on a street.

[88] Captain Robert Gee who was present at the meeting repeated his allegations that the film was fake and had been made for financial profit but was not allowed to publicly speak to the crowd.

The advertising standards watchdog judged that the advert was likely to mislead the general public who had not taken an active interest in the badger cull saying, "The ad must not appear again in its current form.

In response the chairman Mike Tomlinson said "The trustee body continues to place its full support behind the RSPCA's chief executive, management and all our people who do such outstanding work".

Paul Draycott also warned that the RSPCA fears an exodus of "disillusioned staff" with "poor or even non-existent management training and career paths" for employees.

In response the RSPCA's chief executive, Gavin Grant denied suggestions in the memo that there was "no strategy" in some areas, stating that there was no difficulty in attracting trustees or serious internal concerns about management.

[citation needed] In 2016 the new head of the RSPCA, Jeremy Cooper, made a dramatic, public apology for the charity's past mistakes and vowed to be less political and bring fewer prosecutions in the future.

In one particular case 12 horses from a Lancashire farm that had been assessed by vets as being "bright, alert and responsive" and suffering no life-threatening issues were killed by the RSPCA.