Royal manuscripts, British Library

[3] Edward IV is conventionally regarded as the founder of the "old Royal Library" which formed a continuous collection from his reign until its donation to the nation in the 18th century, though this view has been challenged.

[4] There are only about twenty surviving manuscripts that probably belonged to the English kings and queens between Edward I and Henry VI,[5] though the number expands considerably when the princes and princesses are included.

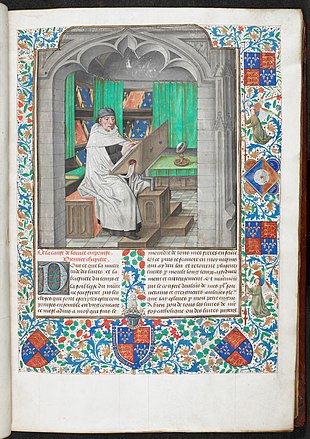

By the late Middle Ages luxury manuscripts would generally include the heraldry of the commissioner, especially in the case of royalty, which is an important means of identifying the original owner.

[7] At the start of Edward III's reign there was a significant library kept in the Privy Wardrobe of the Tower of London, partly built up from confiscations from difficult members of the nobility, which were often later returned.

[9] The reign of Henry IV has left records of the building of a novum studium ("new study") at Eltham Palace finely decorated with more than 78 square feet of stained glass, at a cost of £13, and a prosecution involving nine missing royal books, including bibles in Latin and English, valued respectively at £10 and £5, the high figures suggesting they were illuminated.

He stayed for some of this period in Bruges at the house of Louis de Gruuthuse, a leading nobleman in the intimate circle of Philip the Good, who had died three years before.

Philip had the largest and finest library of illuminated manuscripts in Europe, with perhaps 600, and Gruuthuse was one of several Burgundian nobles who had begun to collect seriously in emulation.

The Burgundian collectors were especially attracted to secular works, often with a military or chivalric flavour, that were illustrated with a lavishness rarely found in earlier manuscripts on such subjects.

Most of his books are large-format popular works in French, with several modern and ancient histories, and authors such as Boccaccio, Christine de Pisan and Alain Chartier.

[18] Henry VII appears to have commissioned relatively few manuscripts, preferring French luxury printed editions (his exile had been spent in France).

Henry retained a scribe with the title "writer of the king's books", from 1530 employing the Fleming Pieter Meghen (1466/67 1540), who had earlier been used by Erasmus and Wolsey.

Meghen and Gerard Horenbout both worked on a Latin New Testament, mixing the gospels in the Vulgate with translations by Erasmus of Acts and the Apocalypse, which has the heraldry of Henry and Catherine of Aragon (Hatfield House MS 324).

Leland was a young Renaissance humanist whose patrons included Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell and was a chaplain to the king with church benefices, by papal dispensation as he was not yet even a subdeacon.

He spent much of the following years touring the country compiling lists of the most significant manuscripts, from 1536 being overtaken by the process of dissolution, as he complained in a famous letter to Cromwell.

A large but unknown number of books were taken for the royal library, others were taken by the expelled monastics or private collectors, but many were simply left in the abandoned buildings; at St Augustine's, Canterbury there were still some remaining in the 17th century.

[26] It is often impossible to trace the origin of monastic manuscripts in or passing through the royal library - a large number of the books initially acquired were later dispersed to a new breed of antiquarian collectors.

Despite the additions from the dissolved monasteries, the collection that survived is very short of medieval liturgical manuscripts, and a high proportion of those that do remain can be shown to have arrived under Mary I or the Stuarts.

[29] The significant addition to the library of Edward's reign, though only completed after his death, was the purchase from his widow of the manuscripts belonging to the reformer Martin Bucer, who had died in England.

Another, Royal 2 B III, is a 13th-century production of Bruges, which was given by "your humbull and poore orytur Rafe, Pryne, grocer of Loundon, wushynge your gras prosperus helthe", as an inscription says.

C. vii, with the Historia Anglorum and Chronica Maiora of Matthew Paris, which had passed from St Albans Abbey to Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester and later Arundel.

The royal library managed to survive relatively unscathed during the English Civil War and Commonwealth, partly because the well-known and aggressive figures on the Parliamentarian side of the preacher Hugh Peters (later executed as a regicide) and the lawyer and M.P.

The major purchase in the reign of Charles II was of 311 volumes in about 1678 from the collection of John Theyer, including the Westminster Psalter (Royal 2.