Royal necropolis of Byblos

The royal necropolis of Byblos is a group of nine Bronze Age underground shaft and chamber tombs housing the sarcophagi of several kings of the city.

The city established major trade links with Egypt during the Bronze Age, resulting in a heavy Egyptian influence on local culture and funerary practices.

The location of ancient Byblos was lost to history, but was rediscovered in the late 19th century by the French biblical scholar and Orientalist Ernest Renan.

On 16 February 1922, heavy rains triggered a landslide in the seaside cliff of Jbeil, exposing an underground tomb containing a massive stone sarcophagus.

The graves of the second group were all robbed in antiquity, making precise dating problematic, but the artifacts indicate that some of the tombs were used into the Late Bronze Age (16th to 11th centuries BC).

Montet compared the function of the Byblos tombs to that of Egyptian mastabas, where the soul of the deceased was believed to fly from the burial chamber, through the funerary shaft, to the ground-level chapel where priests would officiate.

It has taken many names over the ages; it appears as Kebny in 4th-dynasty Egyptian hieroglyphic records, and as Gubla (𒁺𒆷) in the Akkadian cuneiform Amarna letters of 18th-dynasty-Egypt.

[2][3][4] In the second millennium BC, its name appeared in Phoenician inscriptions, such as the Ahiram sarcophagus epitaph, as Gebal (𐤂𐤁𐤋, GBL),[5][6][7] which derives from GB (𐤂𐤁, "well"), and ʾL (𐤀𐤋, "god").

A century and a half later, Egypt expelled the Hyksos and returned Phoenicia under its fold, and effectively defended it against the Mitanni and Hittite invasions.

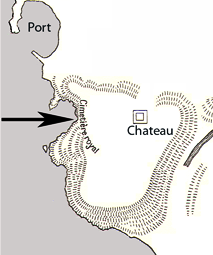

[24][25] Renan correctly posited that the ancient Byblos must have been located atop the circular hill dominated by the Crusader citadel of Jbeil, at the immediate outskirts of the modern city.

[26] On 16 March 1921, Pierre Montet, the Egyptology professor at the University of Strasbourg, addressed a letter to the French archeologist Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau describing Egyptian-inscribed reliefs he had discovered during a 1919 archeological mission in Jbeil.

The next day the administrative advisor of Mount Lebanon informed the Service of Antiquities of the landslide and announced the discovery of an ancient underground tomb containing a large unopened sarcophagus.

[32] Virolleaud arrived at the site to clear and make an inventory of the contents of the unearthed tomb;[31] he continued to supervise the digs and opened the discovered sarcophagus on 26 February 1922.

Earthenware fragments discovered in this tomb, bearing the name of Abishemu in Egyptian hieroglyphs, suggest that its construction date was closer to that of the northern group.

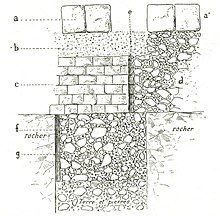

The grave goods were not affected by the landslide; inside the burial chamber the excavators discovered several pottery jars in the damp clay, and a large white limestone sarcophagus with three protruding lugs on its lid by which it could be manipulated.

[47] Four stones were found at the center of the chamber, they supported a wooden coffin that had disintegrated, leaving rich grave goods scattered in the clay.

This Phoenician inscription, dubbed the Byblos Necropolis graffito, is found at a depth of 3 m (9.8 ft) on the south wall of the shaft; it warns looters from entering the grave.

[56] French epigrapher René Dussaud interpreted the inscription as "Avis, voici ta perte (est) ci-dessous" [Beware, here is your loss (is) below].

The excavators found that the wall that closed off the burial chamber had partly collapsed, and the content of the room was disorderly and half-filled with muddy clay.

[71][45][32] These features, along with a number of tomb contents including similarly shaped alabaster containers, suggest that the entire group can be attributed to a restricted time period.

Two bearded effigies measuring 171 cm (5.61 ft) each are carved on either side of the lions; one of the figures bears a wilted lotus flower, the other a live one.

[78] Lebanese archeologist and museum curator Maurice Chehab, who later demonstrated the presence of traces of red paint on the sarcophagus, interpreted the two figures as the deceased king and his son.

[g][87] Tomb I contained a 12 cm (4.7 in) high obsidian vase and lid set with gold, engraved with the enthronement name of Amenemhat III in hieroglyphic characters.

The box rests on four legs, and its lid bears a perfectly preserved Egyptian hieroglyphic cartouche containing the enthronement name and epithets of Amenemhat IV.

[h][91] It is not clear what the contents of the box may have been; similarly shaped receptacles were often depicted on Egyptian tomb friezes and called "pr 'nti" which translate to "house of incense".

Tomb II contained an Egyptian-style, locally produced gem-encrusted gold pectoral with its chain and a shell-shaped cloisonné pendant bearing the name of King Ip-Shemu-Abi.

[93][94] French priest and archeologist Father Louis-Hugues Vincent, Pierre Montet, and other early scholars believed the tombs belonged to the Kings of Byblos of the Middle and Late Bronze Age, based on the characteristics of the painted pottery shards.

[96][97] Montet matched the style of the pottery shards that he uncovered in the shaft of Tomb V to the vases found by English Egyptologist Flinders Petrie in the ruins of the palace of Akhenaten at Amarna.

Both featured large brown or black painted bands, which divide the body of the receptacles into several parts, each of which contained vertical lines and circular motifs.

[105] Montet proposed that Tomb IV was made for a vassal king of Egyptian origin, whom he believes was appointed by Egypt, thus interrupting the Gebalite dynastic suite.