Rudd Concession

Rudd succeeded following a race to the Matabele capital Bulawayo against Edward Arthur Maund, a bidding-rival employed by a London-based syndicate, and after long negotiations with the king and his council of izinDuna (tribal leaders).

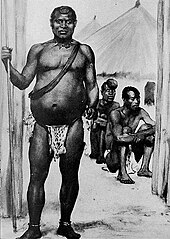

[7] Tall and well built, Lobengula was generally considered thoughtful and sensible, even by contemporary Western accounts; according to the South African big-game hunter Frederick Hugh Barber, who met him in 1875, he was witty, mentally sharp and authoritative—"every inch a king".

[8] Based at his royal kraal at Bulawayo,[n 2] Lobengula was at first open to Western enterprises in his country, adopting Western-style clothing and granting mining concessions and hunting licences to white visitors in return for pounds sterling, weapons and ammunition.

[24] The document proclaimed that the Matabele and British were now at peace, that Lobengula would not enter any kind of diplomatic correspondence with any country apart from Britain, and that the king would not "sell, alienate or cede" any part of Matabeleland or Mashonaland to anybody.

Because Rudd knew little of indigenous African customs and languages, Rhodes added Francis "Matabele" Thompson, an employee of his who had for years run the reserves and compounds that housed the black labourers at the diamond fields.

Robinson was reserved in his answers, saying that he supported the development of Matabeleland by a company with this kind of backing, but did not feel he could commit to endorsing Cawston and Gifford exclusively while there remained other potential concessionaires, most prominently Rhodes—certainly not without unequivocal instructions from Whitehall.

[37] On 14 July, in Bulawayo, agents representing a consortium headed by the South African-based entrepreneur Thomas Leask received a mining concession from Lobengula,[38] covering all of his country, and pledging half of the proceeds to the king.

Robinson wrote to Knutsford on 21 July that he thought Whitehall should back this idea; he surmised that the Boers would receive British expansion into the Zambezi–Limpopo watershed better if it came in the form of a chartered company than if it occurred with the creation of a new Crown colony.

Cawston tersely wrote back with orders to make for Bulawayo without delay, but over a month had passed in the time this written exchange required, and Maund had squandered his head start on Rudd.

[43] After ignoring a notice Lobengula had posted at Tati, barring entry to white big-game hunters and concession-seekers,[44] the Rudd party arrived at the king's kraal on 21 September 1888, three weeks ahead of Maund.

The idea of a mining monopoly in the hands of Rudd's powerful backers was attractive to the Matabele in some ways, as it would end the incessant propositioning for concessions by small-time prospectors, but there was also a case for allowing competition to continue, so that the rival miners would have to compete for Lobengula's favour.

While Lobengula considered the Transvaalers more formidable battlefield adversaries than the British, he understood that Britain was more prominent on the world stage, and while the Boers wanted land, Rudd's party claimed to be interested only in mining and trading.

Rudd reached Kimberley and Rhodes on 19 November 1888, a mere 20 days after the document's signing, and commented with great satisfaction that this marked a record that would surely not be broken until the railway was laid into the interior.

[59] Rumours spread among the kraal's white residents of a freebooter force in the South African Republic that allegedly intended to invade and support Gambo, a prominent inDuna, in overthrowing and killing Lobengula.

[57] While reassuring Thompson and Maguire that he was only repudiating the idea that he had given his country away, and not the concession itself (which he told them would be respected), Lobengula asked Maund to accompany two of his izinDuna, Babayane and Mshete, to England, so they could meet Queen Victoria herself, officially to present to her a letter bemoaning Portuguese incursions on eastern Mashonaland, but also unofficially to seek counsel regarding the crisis at Bulawayo.

"[57] Robinson replied, again in writing; he enclosed a minute from Shippard in which the Bechuanaland official explained how the concession had come about, and expressed the view that the Matabele were less experienced with rifles than with assegais, so their receipt of such weapons did not in itself make them lethally dangerous.

When the envoys reached Kimberley Rhodes told his close friend, associate and housemate Dr Leander Starr Jameson—who himself held the rank of inDuna, having been so honoured by Lobengula years before as thanks for medical treatment—to invite Maund to their cottage.

His mood was markedly different: after looking over Lobengula's message to Queen Victoria, he said that he believed the Matabele expedition to England could actually buttress the concession and associated development plans if the London syndicate would agree to merge its interests with his own and form an amalgamated company alongside him.

[68] In Cape Town, with Rhodes's opposition removed, Robinson altered his stance regarding the Matabele mission, cabling Whitehall that further investigation had shown Babayane and Mshete to be headmen after all, so they should be allowed to board ship for England.

After Helm refused, Tainton translated and transcribed the king's words:[70] I hear it is published in all the newspapers that I have granted a Concession of the Minerals in all my country to CHARLES DUNELL RUDD, ROCHFORD MAGUIRE [sic], and FRANCIS ROBERT THOMPSON.

Thompson, backed by the missionaries, insisted that the agreement only involved the extraction of metals and minerals, and that anything else the concessionaires might do was covered by the concession's granting of "full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure" the mining yield.

On the fourth day of the enquiry, Elliot and Rees, two missionaries based at Inyati, were asked if exclusive mining rights in other countries could be bought for similar sums, as Helm was claiming; they replied in the negative.

[63] Rhodes sent the first shipments of rifles up to Bechuanaland in January and February 1889, sending 250 each month, and instructed Jameson, Dr Frederick Rutherfoord Harris and a Shoshong trader, George Musson, to convey them to Bulawayo.

[74] The audience was originally meant only for the two izinDuna and their interpreter—Maund could not attend such a meeting as he was a British subject—but Knutsford arranged an exception for Maund when Babayane and Mshete refused to go without him; the Colonial Secretary said that it would be regrettable for all concerned if the embassy were derailed by such a technicality.

In April 1891, Renny-Tailyour grandly announced that he and Lobengula had made an agreement: in return for £1,000 up front and £500 annually, the king would bestow on Lippert the exclusive rights to manage lands, establish banks, mint money, and conduct trade in the territory of the Chartered Company.

[89] Lippert's agreement turned out to be an unexpected blessing for Rhodes in that it included a concession on land rights from Lobengula, which the Chartered Company itself lacked, and needed if it were to be recognised by Whitehall as legally owning the occupied territory in Mashonaland.

With Moffat looking on as a witness, Lippert delivered his side of the deal in November 1891, extracting from the Matabele king the exclusive land rights for a century in the Chartered Company's operative territories, including permission to lay out farms and towns and to levy rents, in place of what had been agreed in April.

[96] The next day, Jameson signed a secret agreement with settlers at Fort Victoria, promising each man 6,000 acres (24 km2) of farm land, 20 gold claims and a share of Lobengula's cattle in return for service in a war against Matabeleland.

[9] Jameson sent troops north from Bulawayo to bring the king back, but this column ceased its pursuit in early December after the remnants of Lobengula's army ambushed and annihilated 34 troopers who were sent across the Shangani River ahead of the main force.

[102] During three decades under Company rule, railways, telegraph wires and roads were laid across the territories' previously bare landscape with great vigour, and, with the immigration of tens of thousands of white colonists, prominent mining and tobacco farming industries were created, albeit partly at the expense of the black population's traditional ways of life, which were varyingly disrupted by the introduction of Western-style infrastructure, government, religion and economics.

Hover your mouse over each man for his name; click for more details.