Rudi Dutschke

Controversially for many of those who had protested with him in the 1960s, Dutschke in the 1970s styled himself a patriotic socialist ("Pro Patria Sozi"), and called on the left to re-engage the "national question" and seek a bloc-free path to German reunification.

[3]It was in this religious milieu outside of approved party and state structures, that Dutschke developed the courage (at the cost of any prospect of further education) to refuse compulsory service in the National People's Army and to encourage others to likewise resist conscription.

Its mobilization in workers' councils suggested to him a democratic socialism beyond the official line of the GDR's governing Socialist Unity Party (but consistent with his reading of the Polish and German revolutionary and theorist, Rosa Luxemburg).

[14] While increasingly engaged in consciously Marxist polemics, bolstered by his reading of the socialist theologians Karl Barth and Paul Tillich, Dutschke retained an emphasis on individual conscience and freedom of action.

[12] Dutschke believed he had found the means of transforming these critical perspectives into "praxis" in the dissonant, consciousness-raising provocations of the Situationists (in the propositions of Guy Debord, Rauul Vaneigem, Ivan Chtcheglov and others).

Dutschke spontaneously led the protesters toward Schöneberg Town Hall, seat of the West Berlin House of Representatives, where Tschombé is said to have been hit “full in the face” with tomatoes.

Just as in the Berkeley Free Speech Movement two years earlier, West Berlin students were making a connection between the imperiousness of the university authorities and the broader absence of democratic practice.

Writing in konkret (since revealed to have been subsidised by the East Germans)[29] Sebastian Haffner argued that "with the student pogrom of 2 June 1967 fascism in West Berlin had thrown off its mask".

[17] After Guevara's death as a guerrilla in Bolivia in October 1967, Dutschke and the Chilean Gaston Salvatore translated and wrote an introduction to the Argentinian's last public statement, Message to the Tricontinental, with its famous appeal for "two, three, many Vietnams".

[27] At the beginning of 1968, the SDS decided to organise an international conference in West Berlin, a site chosen as the "intersection" of the rival Cold War blocs and as a "provocation" to the city's American military presence.

In addition to Dutschke, who appeared to direct much of the discussion, they were addressed by Alain Krivine and Daniel Bensaïd (both Jeunesse Communiste Révolutionnaire, JCR) as well as Daniel Cohn-Bendit (Liaison d'Étudiants Anarchistes) from France, Tariq Ali and Robin Blackburn (New Left Review and Vietnam Solidarity Campaign) from Great Britain, Bahman Nirumand (of the international Confederation of Iranian Students) and Bernardine Dohrn (Students for a Democratic Society) from the USA.

[39][40] Characterising the national liberation struggle of the Vietnamese people as an active front in a worldwide socialist revolution, the final declaration charged "US imperialism" with "trying to incorporate the Western European metropolises into its policy of colonial counterrevolution via NATO".

[41] Under the slogan "Smash NATO," and encouraging American soldiers stationed in West Berlin to desert en masse, Dutschke wanted to lead the closing demonstration of more than 15,000 people ("above a sea of red flags rose huge portraits of Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Che Guevara, and Ho Chi Minh")[39] in a march on the U.S. Army McNair Barracks in Berlin-Lichterfelde.

But once the U.S. Command cautioned that it would use force to defend the barracks, and following discussions with the novelist Günter Grass, Bishop Kurt Scharf and the former West Berlin mayor Heinrich Albertz, Dutschke was persuaded that this was a provocation from which it would be best to desist.

[56] The interview in October 1967 on Gaus's SWR programme Zur Person gave Dutschke the kind of media exposure reserved for the Federal Republic's leading statesmen and intellectuals.

"West Berlin supported by direct council democracy" could "be a strategic transmission belt for the future reunification of Germany," triggering by its example an intellectual, and ultimately also political, upheaval in both German states.

When the student leader stepped out of the office to collect a prescription for his newborn son Hosea Che, Bachmann approached him, shouting "you dirty, communist pig", and fired three shots striking him twice in the head and once in the shoulder.

Clare Hall at the University of Cambridge had offered Dutschke the opportunity to complete his doctoral thesis (an analysis of the early Commintern and the differences between Asian and European paths to socialism).

[25] Between January and March 1969, the Dutschkes were guests, outside Dublin, of Conor Cruise O'Brien, who had been distinguished since his UN service during the Congo Crisis by his criticism of U.S. policy both in Vietnam and at home in the repression of the Black Panthers.

During their stay, Rudi and Gretchen Dutschke were visited by their lawyer Horst Mahler, who tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade them to support his underground activity in the group that was to become the Red Army Faction (the "Baader Meinhof Gang").

[25] As the student movement back home splintered and radicalized, the Dutschkes considered staying in Ireland, but returned to the UK in mid-March 1969,[25] proposing as a condition that Rudi avoid engaging in political activity.

[74] At the beginning of 1971 it was an undertaking the UK Home Office believed he had breached, ruling that his meetings with visitors from Germany, Israel, Jordan, Chile and the United States had "far exceeded normal social activities".

[75] In a House of Commons debate on the question of his exclusion, which Labour now in opposition protested, Dutschke was described from governing Conservative benches as "a disciple of Professor Marcuse, who is the patron saint of the urban guerrillas and who is out to destroy the society we hold dear".

Having renewed contact with East Bloc dissidents, in West Germany and abroad (in Norway and in Italy), he critically reviewed the rights record of Warsaw Pact states as well as of the Federal Republic where he made an issue of the bans (Berufsverbot) on the professional employment of those deemed radical (anti-constitutional) leftists.

Every small citizens' initiative, every political and social youth, women, unemployed, pensioner and class struggle movement is a hundred times more valuable and qualitatively different than the most spectacular action of individual terror.

[65] In the autumn of 1976 in an interview with a Stuttgart school newspaper, Dutschke suggested that in other countries the left had a distinct advantage: they could invoke “a national identity”, not of the bourgeoisie, but "of the people and the class in relation to the social movement."

He was an advocate for a new "eco-socialist" constellation that would embrace activists in the anti-nuclear, anti-war, feminist and environmentalist movements but, in contrast to the APO of the sixties, would necessarily exclude Leninists (the communists, the "K-gruppen") and others not in sympathy to the spirit and practice of citizen initiatives (Bürgerinitiativen) and of grass-roots democracy.

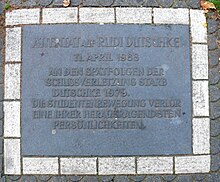

[105][8] In what was reported as a symbolic laying to rest of their "hopes of the 1960s for social change", thousands attended Dutschke's funeral service at St Anne's Parish Church (St. Annen Dorfkirche) in Dahlem, Berlin.

In a party statement, West Berlin's governing Social Democrats described Dutschke's early death as "the terrible price he had to pay for his attempts to change a society whose politicians and news media showed a lack of understanding, maturity, and tolerance".

The renaming, which was suggested by the national daily newspaper Die Tageszeitung (taz), was completed on 30 April 2008 with the unveiling of a street sign on the corner of Rudi-Dutschke-/Axel-Springer-Straße in front of the Axel Springer high-rise.