Rudolf Virchow

While working at the Charité hospital, his investigation of the 1847–1848 typhus epidemic in Upper Silesia laid the foundation for public health in Germany, and paved his political and social careers.

Academically brilliant, he always topped his classes and was fluent in German, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, English, Arabic, French, Italian and Dutch.

[18] Unlike his German peers, Virchow had great faith in clinical observation, animal experimentation (to determine causes of diseases and the effects of drugs) and pathological anatomy, particularly at the microscopic level, as the basic principles of investigation in medical sciences.

His first major work there was a six-volume Handbuch der speciellen Pathologie und Therapie (Handbook on Special Pathology and Therapeutics) published in 1854.

[30] Virchow was particularly influenced in cellular theory by the work of John Goodsir of Edinburgh, whom he described as "one of the earliest and most acute observers of cell-life both physiological and pathological".

)[43] He made a crucial observation that certain cancers (carcinoma in the modern sense) were inherently associated with white blood cells (which are now called macrophages) that produced irritation (inflammation).

[44] It was realised that specific cancers (including those of mesothelioma, lung, prostate, bladder, pancreatic, cervical, esophageal, melanoma, and head and neck) are indeed strongly associated with long-term inflammation.

While other physicians such as Ernst von Bergmann suggested surgical removal of the entire larynx, Virchow was opposed to it because no successful operation of this kind had ever been done.

"[59] Having made these initial discoveries based on autopsies, he proceeded to put forward a scientific hypothesis; that pulmonary thrombi are transported from the veins of the leg and that the blood has the ability to carry such an object.

This work rebutted a claim made by the eminent French pathologist Jean Cruveilhier that phlebitis led to clot development and that thus coagulation was the main consequence of venous inflammation.

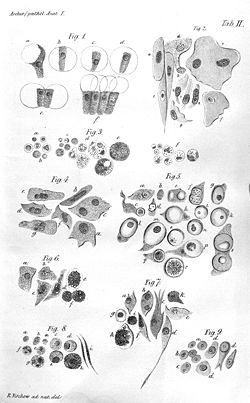

His most important work in the field was Cellular Pathology (Die Cellularpathologie in ihrer Begründung auf physiologische und pathologische Gewebelehre) published in 1858, as a collection of his lectures.

Virchow noticed a mass of circular white flecks in the muscle of dog and human cadavers, similar to those described by Richard Owen in 1835.

[20][72] His autopsy on a baby in 1856 was the first description of congenital pulmonary lymphangiectasia (the name given by K. M. Laurence a century later), a rare and fatal disease of the lung.

[75][76] Virchow discovered the clinical syndrome which he called ochronosis, a metabolic disorder in which a patient accumulates homogentisic acid in connective tissues and which can be identified by discolouration seen under the microscope.

[81] His testimony runs: [T]he hairs found on the defendant do not possess any so pronounced peculiarities or individualities [so] that no one with certainty has the right to assert that they must have originated from the head of the victim.

[89] On 22 September 1877, he delivered a public address entitled "The Freedom of Science in the Modern State" before the Congress of German Naturalists and Physicians in Munich.

[90][91] Ernst Haeckel, who had been Virchow's student, later reported that his former professor said that "it is quite certain that man did not descend from the apes...not caring in the least that now almost all experts of good judgment hold the opposite conviction.

With this reasoning, Virchow "judged Darwin an ignoramus and Haeckel a fool and was loud and frequent in the publication of these judgments,"[96] and declared that "it is quite certain that man did not descend from the apes.

[100] His campaign was because of Herman Müller, a school teacher who was banned because of his teaching a year earlier on the inanimate origin of life from carbon.

[102] Years later, the noted German physician Carl Ludwig Schleich would recall a conversation he held with Virchow, who was a close friend of his: "...On to the subject of Darwinism.

'"[103] Virchow's ultimate opinion about evolution was reported a year before he died; in his own words: The intermediate form is unimaginable save in a dream... We cannot teach or consent that it is an achievement that man descended from the ape or other animal.Virchow's anti-evolutionism, like that of Albert von Kölliker and Thomas Brown, did not come from religion, since he was not a believer.

[16] Virchow believed that Haeckel's monist propagation of social Darwinism was in its nature politically dangerous and anti-democratic, and he also criticized it because he saw it as related to the emergent nationalist movement in Germany, ideas about cultural superiority,[106][107][108] and militarism.

[109] In 1885, he launched a study of craniometry, which gave results contradictory to contemporary scientific racist theories on the "Aryan race", leading him to denounce the "Nordic mysticism" at the 1885 Anthropology Congress in Karlsruhe.

[112] He even attacked Koch's and Ignaz Semmelweis' policy of handwashing as an antiseptic practice, who said of him: "Explorers of nature recognize no bugbears other than individuals who speculate.

His political views are evident in his Report on the Typhus Outbreak of Upper Silesia, where he states that the outbreak could not be solved by treating individual patients with drugs or with minor changes in food, housing, or clothing laws, but only through radical action to promote the advancement of an entire population, which could be achieved only by "full and unlimited democracy" and "education, freedom and prosperity".

This secondary position in Berlin convinced him to accept the chair of pathological anatomy at the medical school in the provincial town of Würzburg, where he continued his scientific research.

It has Virchow, being the one challenged and therefore entitled to choose the weapons, selecting two pork sausages, one loaded with Trichinella larvae, the other safe; Bismarck declined.

They had three sons and three daughters:[129] Virchow broke his thigh bone on 4 January 1902, jumping off a running streetcar while exiting the electric tramway.

[18][131] A state funeral was held on 9 September in the Assembly Room of the Magistracy in the Berlin Town Hall, which was decorated with laurels, palms and flowers.

In addition, Virchow's collection of anatomical specimens from numerous European and non-European populations, which still exists today, deserves special mention.