Rules of chess

While the exact origins of chess are unclear, modern rules first took form during the Middle Ages.

The rules continued to be slightly modified until the early 19th century, when they reached essentially their current form.

Today, the standard rules are set by FIDE (Fédération Internationale des Échecs), the international governing body for chess.

The pieces are placed, one per square, as follows:[3] Popular mnemonics used to remember the setup are "queen on her own color" and "white on right".

Play continues until a king is checkmated, a player resigns, or a draw is declared, as explained below.

Instead, this decision is left open to tournament-specific rules (e.g. a Swiss system tournament or round-robin tournament) or, in the case of casual play, mutual agreement, in which case some kind of random choice such as flipping a coin can be employed.

[24] The game ends in a draw if any of these conditions occur:[27] In addition, in the FIDE rules, if a player has run out of time (see below), or has resigned, but the position is such that there is no way for the opponent to give checkmate by any series of legal moves, the game is a draw.

[34] According to the rules of chess the game is immediately terminated the moment a dead position appears on the board.

USCF rules, for games played under a time control that does not include delay or increment, allow draw claims for "insufficient losing chances".

The touch-move rule is a fundamental principle in chess, ensuring that players commit to moves deliberated mentally, without physically experimenting on the board.

Special considerations apply for castling and pawn promotion, reflecting their unique nature in the game.

They mention timing (chess clocks), arbiters (or, in USCF play, directors), keeping score, and adjournment.

[58] In formal competition, each player is obliged to record each move as it is played in algebraic chess notation in order to settle disputes about illegal positions, overstepping time control, and making claims of draws by the fifty-move rule or repetition of position.

The current rule is that a move must be made on the board before it is written on paper or recorded with an electronic device.

[71][f] According to the FIDE Laws of Chess, the first stated completed illegal move results in a time penalty.

[73] The second stated completed illegal move by the same player results in the loss of the game,[72] unless the position is such that it is impossible for the opponent to win by any series of legal moves (e.g. if the opponent has a bare king) in which case the game is drawn.

If it is discovered that an illegal move has been made, or that pieces have been displaced, the game is restored to the position before the irregularity.

Generally a player should not speak during the game, except to offer a draw, resign, or to call attention to an irregularity.

[84] Due to increasing concerns about the use of chess engines and outside communication, mobile phone usage is banned.

[85] In 2014 FIDE extended this to ban all mobile phones from the playing area during chess competitions, under penalty of forfeiture of the game or even expulsion from the tournament.

The modern rules first took form in southern Europe during the 13th century, giving more mobility to pieces that previously had more restricted movement (such as the queen and bishop).

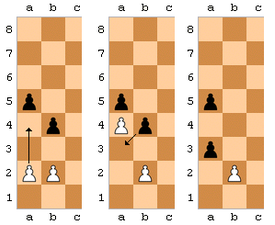

[100] In the Middle Ages the pawn could only be promoted to the equivalent of a queen (which at that time was a weak piece) if it reached its eighth rank.

[110] The first known publication of chess rules was in a book by Luis Ramírez de Lucena about 1497, shortly after the movement of the queen, bishop, and pawn were changed to their modern form.

[112] In the 16th and 17th centuries, there were local differences concerning rules such as castling, promotion, stalemate, and en passant.

In the 19th century, many major clubs published their own rules, including The Hague in 1803, London in 1807, Paris in 1836, and St. Petersburg in 1854.

In 1851 Howard Staunton (1810–1874) called for a "Constituent Assembly for Remodeling the Laws of Chess" and proposals by Tassilo von Heydebrand und der Lasa (1818–1889) were published in 1854.

German-speaking countries usually used the writings of chess authority Johann Berger (1845–1933) or Handbuch des Schachspiels by Paul Rudolf von Bilguer (1815–1840), first published in 1843.

Throughout this time, ambiguities in the laws were handled by frequent interpretations that the Rules Commission published as supplements and amendments.

Chess960 uses a random initial set-up of main pieces, with the conditions that the king is placed somewhere between the two rooks, and bishops on opposite-color squares.

[86] Under FIDE's Laws of Chess, tournament organizers have the option to parameterize some rules to fit their events.