Ryukyu independence movement

[1] Some support the restoration of the Ryukyu Kingdom, while others advocate the establishment of a Republic of the Ryukyus (Japanese: 琉球共和国, Kyūjitai: 琉球共和國, Hepburn: Ryūkyū Kyōwakoku).

It is highly critical of the abuses of Ryukyuan people and territory, both in the past and in the present day (such as the use of Okinawan land to host American military bases).

[6] In addition to Korea (1392), Thailand (1409) and other Southeast Asian polities, the kingdom maintained trade relations with Japan (1403), and during this period a unique political and cultural identity emerged.

The Ryukyu's aristocratic class resisted annexation for almost two decades[10] but after the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), factions pushing for Chinese and Ryukyuan sovereignty faded as China renounced its claims to the island.

[19] In 1957, Kiyoshi Inoue argued that the Ryukyu Shobun was an annexation of an independent country over the opposition of its people, thus constituting an act of aggression and not a "natural ethnic unification".

[27][28] Okinawan historian Higashionna Kanjun in 1909 warned the Ryukyuans that if they forget their historical and cultural heritage then "their native place is no different from a country built on a desert or a new colony".

[30] The anxiety about the issue of Okinawa being part of Japan was so extreme that even attempts to discuss it were discredited and denounced from both mainland and Okinawan community itself, as a failure of being national subjects.

[35] However, the state did valorize and protect some aspects like being "people of the sea", folk art (pottery, textiles) and architecture, although it defined these cultural elements as being Japonic in essence.

[36] The Okinawan's use of heritage as a basis for political identity in the post-war period was interesting to the occupying United States forces who decided to support the pre-1879 culture and claims to autonomy in hopes that their military rule would be embraced by the population.

[9] Japan and the United States are both responsible for the colonial status of Okinawa – used first as a trade negotiator with China, later as a place to fight battles or establish military bases.

The constitution's Article 9 (respect for the sovereignty of the people) is violated by the stationing of American military troops, as well as the lack of protection for civilians' human rights.

They considered it as an organization emerging primarily among Okinawan's emigrants, specifically in Peru, because the territory of Ryukyu and its population were too small to make the movement's success attainable.

[65] In November 1971, information was leaked that the reversion agreement would ignore the Okinawans' demands and that Japan was collaborating with the United States to maintain a military status quo.

[66] Since 1972, because of a lack of any anticipated developments in relation to the US-Japan alliance, committed voices have turned once again towards the aim of "Okinawa independence theory", on the basis of cultural heritage and history, at least by poets and activists like Takara Ben and Shoukichi Kina,[65] and on a theoretical level in academic journals.

The Okinawan branch of NHK and newspaper Ryūkyū Shimpō sponsored a forum for the discussion of reversion, assimilation to the Japanese polity, as well as the costs and opportunities of Ryukyuan independence.

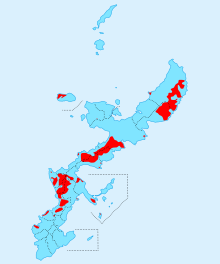

In April 1996, a joint US-Japanese governmental commission announced that it would address Okinawan's anger, reducing the U.S. military foot-print and returning part of the occupied land in the center of Okinawa (only around 5%[citation needed]), including the large Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, located in a densely populated area.

[70] However, while initially considered as a positive change, in September 1996 the public became aware that the U.S. planned to "give up" Futenma for construction of a new base (first since the 1950s) in the north offshore, Oura Bay, near Henoko (relatively less populated than Ginowan) in the municipality of Nago.

[71][5] The villagers organized a movement called "Inochi o Mamorukai" ("Society for the protection of life"), and demanded a special election while maintaining a tent city protest on the beach, and a constant presence on the water in kayaks.

The subsequent ministers acted as clients for the United States, while in 2013 Shinzō Abe and Barack Obama affirmed their commitment to build the new base, regardless of the local protests.

[75] In September 2015, Governor Onaga went to base his arguments to the United Nations human rights body,[76] but in December 2015, the work resumed as the Supreme Court of Japan ruled against Okinawa's opposition, a decision which erupted new protests.

[84] In 2007, 110,000 people protested due to Ministry of Education's textbook revisions (see MEXT controversy) of the Japanese military's ordering of mass suicide for civilians during the Battle of Okinawa.

[85][86] The journal Ryūkyū Shimpō and scholars Tatsuhiro Oshiro, Nishizato Kiko in their essays considered the U.S. bases in Okinawa a continuation of Ryukyu Shobun to the present day.

It posited three basic paths; 1) leveraging Article 95 and exploring the possibilities of decentralization 2) seeking formal autonomy with the right to diplomatic relations 3) full independence.

[98]Literary and political journals like Sekai (Japan), Ke-shi Kaji and Uruma neshia (Okinawa) began to frequently write on the issue of autonomy, and numerous books about the topic have been published.

The LDP Governor Hirokazu Nakaima (2006–2014), who approved the government's permit for the construction of military base, was defeated in November 2014 election by Takeshi Onaga, who ran on a platform that was anti-Futenma relocation, and pro-Okinawan self-determination.

[104] In February of the same year, Uruma-no-Kai group which promotes the solidarity between Ainu and Okinawans, organized a symposium at Okinawa International University on the right of their self-determination.

Professor Yasukatsu Matsushima expressed his fear of the possibility that Ryukyu independence would be used as a tool, perceiving Chinese support as "strange" since they deny it to their own minorities.

[113][114][115][116] In light of the Okinawan newspaper articles, Tetsuhide Yamaoka [ja], who supervised the Japanese translation of the Silent Invasion written by Clive Hamilton, gave a lecture titled "Silent Invasion: What Okinawans Want You to Know About China's Gentry Craft" at the Urasoe City Industrial Promotion Center on October 10, 2020, organized by the Japan Okinawa Policy Research Forum.

[130][131] On October 3, 2024, Nikkei Asia, in collaboration with a cyber security company, confirmed that there has been an increase in Chinese-language disinformation on social media promoting Ryukyuan independence, which are being spread by some suspected influence accounts.

[144] Therefore, it is believed that Yaeyama, Miyakojima, and Yonaguni Island introduced modern institutions, taxation system, and freedom to choose an occupation after the Meiji Restoration in Japan as a result of the Ryukyu dispositions.