Vega

This causes the equator to bulge outward due to centrifugal effects, and, as a result, there is a variation of temperature across the star's photosphere that reaches a maximum at the poles.

With a declination of +38.78°, Vega can only be viewed at latitudes north of 51° S. Therefore, it does not rise at all anywhere in Antarctica or in the southernmost part of South America, including Punta Arenas, Chile (53° S).

[32] Complementarily, Vega swoops down and kisses the horizon at true North at midnight on Dec 31/Jan 1, as seen from 51° N. Each night the positions of the stars appear to change as the Earth rotates.

A complete precession cycle requires 25,770 years,[33] during which time the pole of the Earth's rotation follows a circular path across the celestial sphere that passes near several prominent stars.

On 17 July 1850, Vega became the first star (other than the Sun) to be photographed, when it was imaged by William Bond and John Adams Whipple at the Harvard College Observatory, also with a daguerreotype.

[38] In 1879, William Huggins used photographs of the spectra of Vega and similar stars to identify a set of twelve "very strong lines" that were common to this stellar category.

[48] The UBV photometric system measures the magnitude of stars through ultraviolet, blue and yellow filters, producing U, B and V values, respectively.

[49] Thus, Vega has a relatively flat electromagnetic spectrum in the visual region—wavelength range 350–850 nanometers, most of which can be seen with the human eye—so the flux densities are roughly equal; 2,000–4,000 Jy.

[51] Photometric measurements of Vega during the 1930s appeared to show that the star had a low-magnitude variability on the order of ±0.03 magnitude (around ±2.8%[note 1] luminosity).

[59] Vega's spectral class is A0V, making it a blue-tinged white main-sequence star that is fusing hydrogen to helium in its core.

Since more massive stars use their fusion fuel more quickly than smaller ones, Vega's main-sequence lifetime is roughly one billion years, a tenth of the Sun's.

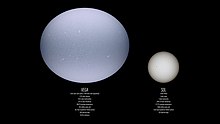

Because it is rotating rapidly, approximately once every 16.5 hours,[14] and seen nearly pole-on, its apparent luminosity, calculated assuming it was the same brightness all over, is about 57 times the Sun's.

The temperature gradient may also mean that Vega has a convection zone around the equator,[12][75] while the remainder of the atmosphere is likely to be in almost pure radiative equilibrium.

As Vega had long been used as a standard star for calibrating telescopes, the discovery that it is rapidly rotating may challenge some of the underlying assumptions that were based on it being spherically symmetric.

One possibility is that the chemical peculiarity may be the result of diffusion or mass loss, although stellar models show that this would normally only occur near the end of a star's hydrogen-burning lifespan.

Motion transverse to the line of sight causes the position of Vega to shift with respect to the more distant background stars.

[86] Based on this star's kinematic properties, it appears to belong to a stellar association called the Castor Moving Group.

[88] The latter is the result of radiation pressure creating an effective force that opposes the orbital motion of a dust particle, causing it to spiral inward.

[90] Following the discovery of an infrared excess around Vega, other stars have been found that display a similar anomaly that is attributable to dust emission.

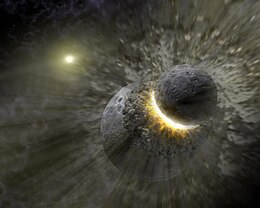

The disk of dust is produced as radiation pressure from Vega pushes debris from collisions of larger objects outward.

However, continuous production of the amount of dust observed over the course of Vega's lifetime would require an enormous starting mass—estimated as hundreds of times the mass of Jupiter.

This dusty disk would be relatively young on the time scale of the star's age, and it will eventually be removed unless other collision events supply more dust.

[23] Observations, first with the Palomar Testbed Interferometer by David Ciardi and Gerard van Belle in 2001[91] and then later confirmed with the CHARA array at Mt.

[95] The Hubble observation is the first image of the disk in scattered light and found an outer halo made up of small dust grains.

This hot infrared excess lies within about 0.2 AU or closer and is made up of small grains, like graphite and iron and manganese oxides, which was previously verified.

[25] Observations from the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in 1997 revealed an "elongated bright central region" that peaked at 9″ (70 AU) to the northeast of Vega.

[102] Using a coronagraph on the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii in 2005, astronomers were able to further constrain the size of a planet orbiting Vega to no more than 5–10 times the mass of Jupiter.

[103] The issue of possible clumps in the debris disc was revisited in 2007 using newer, more sensitive instrumentation on the Plateau de Bure Interferometer.

Cornelius Agrippa listed its kabbalistic sign under Vultur cadens, a literal Latin translation of the Arabic name.

[32] W. H. Auden's 1933 poem "A Summer Night (to Geoffrey Hoyland)"[126] famously opens with the couplet, "Out on the lawn I lie in bed,/Vega conspicuous overhead".