SIM card

SIMs are also able to store address book contacts information,[1] and may be protected using a PIN code to prevent unauthorized use.

[12] Today, SIM cards are considered ubiquitous, allowing over 8 billion devices to connect to cellular networks around the world daily.

[13] The rise of cellular IoT and 5G networks was predicted by Ericsson to drive the growth of the addressable market for SIM cards to over 20 billion devices by 2020.

[16] A multi-company collaboration called GlobalPlatform defines some extensions on the cards, with additional APIs and features like more cryptographic security and RFID contactless use added.

The most important of these are the ICCID, IMSI, authentication key (Ki), local area identity (LAI) and operator-specific emergency number.

As required by E.118, the ITU-T updates a list of all current internationally assigned IIN codes in its Operational Bulletins which are published twice a month (the last as of January 2019 was No.

[23] SIM cards are identified on their individual operator networks by a unique international mobile subscriber identity (IMSI).

Authentication process: The SIM stores network state information, which is received from the location area identity (LAI).

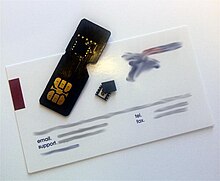

[25] The micro-SIM was introduced by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) along with SCP, 3GPP (UTRAN/GERAN), 3GPP2 (CDMA2000), ARIB, GSM Association (GSMA SCaG and GSMNA), GlobalPlatform, Liberty Alliance, and the Open Mobile Alliance (OMA) for the purpose of fitting into devices too small for a mini-SIM card.

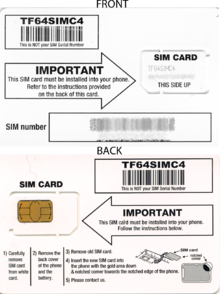

Retaining the same contact area makes the micro-SIM compatible with the prior, larger SIM readers through the use of plastic cutout surrounds.

The chairman of EP SCP, Klaus Vedder, said[27] ETSI has responded to a market need from ETSI customers, but additionally there is a strong desire not to invalidate, overnight, the existing interface, nor reduce the performance of the cards.Micro-SIM cards were introduced by various mobile service providers for the launch of the original iPad, and later for smartphones, from April 2010.

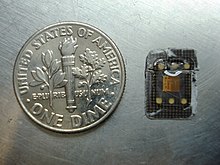

[28][29] The nano-SIM (or 4FF) card was introduced in June 2012, when mobile service providers in various countries first supplied it for phones that supported the format.

[30] A small rim of isolating material is left around the contact area to avoid short circuits with the socket.

The nano-SIM can be put into adapters for use with devices designed for 2FF or 3FF SIMs, and is made thinner for that purpose,[31] and telephone companies give due warning about this.

In July 2013, Karsten Nohl, a security researcher from SRLabs, described[34][35] vulnerabilities in some SIM cards that supported DES, which, despite its age, is still used by some operators.

[37] In February 2015, The Intercept reported that the NSA and GCHQ had stolen the encryption keys (Ki's) used by Gemalto (now known as Thales DIS, manufacturer of 2 billion SIM cards annually) [38]), enabling these intelligence agencies to monitor voice and data communications without the knowledge or approval of cellular network providers or judicial oversight.

[39] Having finished its investigation, Gemalto claimed that it has “reasonable grounds” to believe that the NSA and GCHQ carried out an operation to hack its network in 2010 and 2011, but says the number of possibly stolen keys would not have been massive.

Within these development cycles, the SIM specification was enhanced as well: new voltage classes, formats and files were introduced.

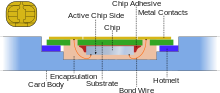

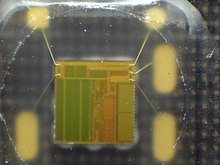

[46] The surface mount format provides the same electrical interface as the full size, 2FF and 3FF SIM cards, but is soldered to a circuit board as part of the manufacturing process.

[47][48] The eSIM standard, initially introduced in 2016, has progressively supplanted traditional physical SIM cards across various sectors, notably in cellular telephony.

As a consequence they are smaller, cheaper and more reliable than eSIMs, they can improve security and ease the logistics and production of small devices i.e. for IoT applications.

The Subscriber Identity Module Expert Group was a committee of specialists assembled by the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) to draw up the specifications (GSM 11.11) for interfacing between smart cards and mobile telephones.

CDMA-based devices originally did not use a removable card, and the service for these phones is bound to a unique identifier contained in the handset itself.

The equivalent of a SIM in UMTS is called the universal integrated circuit card (UICC), which runs a USIM application.

By 2011 they existed in over 50 countries, including most of Europe, the United States, Canada, Mexico, Australia and parts of Asia, and accounted for approximately 10% of all mobile phone subscribers around the world.

This is more common in markets where mobile phones are heavily subsidised by the carriers, and the business model depends on the customer staying with the service provider for a minimum term (typically 12, 18 or 24 months).

The duration of a SIM-only contract varies depending on the deal selected by the customer, but in the UK they are typically available over 1, 3, 6, 12 or 24-month periods.

The short contract length is one of the key features of SIM-only – made possible by the absence of a mobile device.

Increasing smartphone penetration combined with financial concerns is leading customers to save money by moving onto a SIM-only when their initial contract term is over.

Similar devices have also been developed for iPhones to circumvent SIM card restrictions on carrier-locked models.