Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird

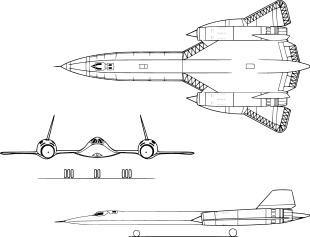

[2] Its shape was based on the Lockheed A-12, a pioneer in stealth technology with its reduced radar cross section, but the SR-71 was longer and heavier to carry more fuel and a crew of two in tandem cockpits.

[21] During the 1964 campaign, Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater repeatedly criticized President Lyndon B. Johnson and his administration for falling behind the Soviet Union in developing new weapons.

Aerodynamicists initially opposed the concept, disparagingly referring to the aircraft as a Mach 3 variant of the 1920s-era Ford Trimotor, which was known for its corrugated aluminum skin.

Early studies in stealth technology indicated that a shape with flattened, tapering sides would reflect most radar energy away from a beam's place of origin, so Lockheed's engineers added chines and canted the vertical control surfaces inward.

Landing speeds were also reduced, as the chines' vortices created turbulent flow over the wings at high angles of attack, making it harder to stall.

[65] Designer David Campbell holds a patent on the inlet's aerodynamic features and functioning,[66] which are explained in the "A-12 Utility Flight Manual"[67] and in a 2014 presentation by Lockheed Technical Fellow Emeritus Tom Anderson.

[83] His solution was to 1) incorporate six air-bleed tubes, prominent on the outside of the engine, to transfer 20% of the compressor air to the afterburner, and 2) to modify the inlet guide vanes with a 2-position, trailing edge flap.

[89] For the Blackbird powerplant the nozzle was more efficient structurally (lighter) by incorporating it as part of the airframe because it carried fin and wing loads through the ejector shroud.

[92] On a typical mission, the SR-71 took off with a partial fuel load to reduce stress on the brakes and tires during takeoff and also ensure it could successfully take off should one engine fail.

[21] It is a common misconception that the planes refueled shortly after takeoff because the fuel tanks, which formed the outer skin of the aircraft, leaked on the ground.

[99] On hot days, when approaching the maximum fuel load of 80,285 lb (36,415 kg),[100] the left engine had to be run with minimum afterburner to maintain probe contact.

In flight, the ANS, which sat behind the reconnaissance systems officer's (RSO's), position, tracked stars through a circular quartz glass window on the upper fuselage.

In the later years of its operational life, a datalink system could send ASARS-1 and ELINT data from about 2,000 nmi (3,700 km) of track coverage to a suitably equipped ground station.

[129] During its career, this aircraft (976) accumulated 2,981 flying hours and flew 942 total sorties (more than any other SR-71), including 257 operational missions, from Beale AFB; Palmdale, California; Kadena Air Base, Okinawa, Japan; and RAF Mildenhall, UK.

[135] While deployed at Okinawa, the SR-71s and their aircrew members gained the nickname Habu (as did the A-12s preceding them) after a pit viper indigenous to Japan, which the Okinawans thought the plane resembled.

[1] Operational highlights for the entire Blackbird family (YF-12, A-12, and SR-71) as of about 1990 included:[136] Only one crew member, Jim Zwayer, a Lockheed flight-test reconnaissance and navigation systems specialist, was killed in a flight accident.

This meant that NATO aircraft entering the Baltic Sea had to fly through a narrow corridor of international airspace between Scania and Western Pomerania, which was monitored by both the Swedish and Soviet Air Forces.

Starting a counter-clockwise 30-minute loop, the Blackbirds would then reconnoiter along the Soviet Union's coastal border, before slowing down to Mach 2.54 to make a left turn south of Åland, and then follow the Swedish coast back towards Denmark.

[141] Swedish radar stations would observe the 15th Air Army dispatch Su-15s from Latvia, and MiG-21s and MiG-23s from Estonia, although only the Sukhois would have even a slim chance of successfully intercepting the American aircraft.

Limited by a top speed of Mach 2.1 and a service ceiling of 18 kilometres (11 mi), the Viggen pilots would line up for a frontal attack, and rely on their state-of-the-art avionics to climb at the right time and attain a missile lock on the SR-71.

[141][142][150] The event had been classified for over 30 years, and when the report was unsealed, data from the NSA showed that multiple MiG-25s with the order to shoot down the SR-71 or force it to land, had started right after the engine failure.

[150] The two most widely proposed reasons for the SR-71's retirement in 1989, offered by the Air Force to Congress, were that the plane was too expensive to build and maintain, and had been rendered redundant by other evolving reconnaissance methods, such as unmanned vehicles (UAVs) and satellites.

[160] Four months after the plane's retirement, General Norman Schwarzkopf Jr., was told that the expedited reconnaissance, which the SR-71 could have provided, was unavailable during Operation Desert Storm.

[161] Rear Admiral Thomas F. Hall addressed the question of why the SR-71 was retired, saying it was under "the belief that, given the time delay associated with mounting a mission, conducting a reconnaissance, retrieving the data, processing it, and getting it out to a field commander, that you had a problem in timelines that was not going to meet the tactical requirements on the modern battlefield.

And the determination was that if one could take advantage of technology and develop a system that could get that data back real time... that would be able to meet the unique requirements of the tactical commander."

Retired USAF Colonels Don Emmons and Barry MacKean were put under government contract to remake the plane's logistic and support structure.

Still-active USAF pilots and Reconnaissance Systems Officers (RSOs) who had worked with the aircraft were asked to volunteer to fly the reactivated planes.

[168] The reactivation met much resistance: the USAF had not budgeted for the aircraft, and UAV developers worried that their programs would suffer if money was shifted to support the SR-71s.

[178] When the SR-71 was retired in 1990, one Blackbird was flown from its birthplace at USAF Plant 42 in Palmdale, California, to go on exhibit at what is now the Smithsonian Institution's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.

[234] Data from Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird[235]General characteristics Performance Avionics 3,500 lb (1,588 kg) of mission equipment Related development Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era