SS Great Eastern

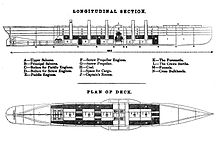

SS Great Eastern was an iron-hulled steamship designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, and built by John Scott Russell & Co. at Millwall Iron Works on the River Thames, London, England.

Powered by both sidewheels and screw propellers, she was by far the largest ship ever built at the time of her 1858 launch, and had the capacity to carry 4,000 passengers from England to Australia without refuelling.

[4] After repairs, she plied for several years as a passenger liner between Britain and North America before being converted to a cable-laying ship and laying the first lasting transatlantic telegraph cable in 1866.

[8] Brunel showed his idea to John Scott Russell, an experienced naval architect and ship builder whom he had first met at the Great Exhibition.

[7] Brunel entered into a partnership with John Scott Russell, an experienced naval architect and ship builder, to build Great Eastern.

Her roughly 30,000 iron plates weighed 340 kilograms (1⁄3 long ton) each, and were cut over individually-made wooden templates before being rolled to the required curvature.

[12] On 3 November, a large crowd gathered to watch the ship launch, with notables present including the Comte de Paris, the Duke of Aumale, and the Siamese ambassador to Britain.

[12] Advice sent to Brunel on how to launch the ship came from a number of sources, including steamboat captains on the Great Lakes and one admirer who wrote an insightful description on how the massive Bronze Horseman had been erected in Saint Petersburg.

[13] With the building company already in debt, cost cutting measures were implemented; the ship was removed from Russell's shipyard, and many investors requested she be sold.

Fitting out concluded in August 1859 and was marked with a lavish banquet for visitors (which included engineers, stockholders, members of parliament, 5 earls, and other notables).

However, off Hastings she suffered a massive steam explosion (caused by a valve being left shut by accident after a pressure test of the system) that killed five crewmen and destroyed the forwardmost funnel.

However, relations between the crew and New Yorkers began to sour – the public was outraged by the $1 entry fee (similar excursion trips in New York charged 25 cents) and many would-be visitors decided to forego visiting the ship.

[14] Great Eastern left New York in late July, taking several hundred passengers on an excursion trip to Cape May and then to Old Point, Virginia.

During the presidential visit, one member of the company board discussed sending the ship to Savannah to transport Southern cotton to English mills, but this idea was never followed up on.

[20] Upon her return to Britain, it was announced that the ship's company had been contracted by the British War Office to transport 2,000 troops to Canada, part of a show of force to intimidate the rapidly-arming United States.

A jury-rigged propeller was installed by Hamilton Towle (an American engineer returning from Austria), allowing the ship to steer for Ireland powered only by her screw.

By July 1862, the ship was turning its first noteworthy profits, carrying 500 passengers and 8,000 tons of foodstuffs from New York to Liverpool, bringing in $225,000 in gross and requiring a turnaround of only 11 days.

However, as noted by sources, the ship's owners struggled to sustain this profitability as they were heavily focused on upper and middle class passenger service.

[22] On 17 August 1862, Great Eastern departed from Liverpool for New York, carrying 820 passengers and several thousand tons of cargo – given the size of her load, she was drawing 9 metres (30 ft) of water.

Fearing that Great Eastern was resting too low in the water to pass by Sandy Hook, the ship's captain instead chose the nominally safer route through Long Island Sound.

The collision was noticed by the crew, who guessed that the ship had struck a shifting sand shoal, and after a bilge check Great Eastern continued onto New York without incident.

Upon her arrival in port, Great Eastern's size generated considerable public interest, with the captain offering tickets to view the ship for 2 rupees apiece, distributing proceeds to the crew.

[15] At the end of her cable-laying career – hastened by the launch of the CS Faraday, a ship purpose-built for cable laying[15] – she was refitted as a liner, but once again efforts to make her a commercial success failed.

[35] Sold again after the exhibition, one company considered using her to raise shallow shipwrecks, while one humorist suggested that Great Eastern be used to help dig the Panama canal by ramming her into the isthmus.

Parts of Great Eastern were repurposed for other uses; one ferry company converted her wood paneling into a public house bar, while one mistress at a Lancashire boarding school acquired the ship's deck caboose for use as a children's playhouse.

[15] An early example of breaking-up a structure by use of a wrecking ball, she was scrapped near the Sloyne, at New Ferry on the River Mersey by Henry Bath & Son Ltd in 1889–1890—it took 18 months to take her apart, with her double hull being particularly difficult to salvage.

Other authors, notably L. T. C. Rolt in his biography of Brunel, have dismissed the claim (noting such a discovery would have been recorded in company logs and received press attention), but the legend has become widely mentioned in books and articles about nautical ghost stories.

[41] Brian Dunning wrote about the legend in 2020, noting that while it was technically impossible to prove or disprove, the incident could not have happened given the lack of evidence being found during the numerous times Great Eastern was being repaired.

[44] In 2011, the Channel 4 programme Time Team found geophysical survey evidence to suggest that residual iron parts from the ship's keel and lower structure still reside in the foreshore.

The funnel was salvaged and subsequently purchased by the water company supplying Weymouth and Melcombe Regis in Dorset, UK, and used as a filtering device.