STS-3xx

The planning and training processes for a rescue flight would allow NASA to launch the mission within a period of 40 days of its being called up.

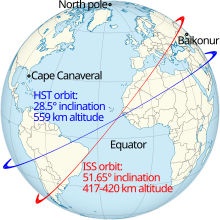

During that time the damaged (or disabled) shuttle's crew would have to take refuge on the International Space Station (ISS).

A number of pieces of Launch on Need flight hardware were built in preparation for a rescue mission including: The Remote Control Orbiter (RCO), also known as the Autonomous Orbiter Rapid Prototype (AORP), was a term used by NASA to describe a shuttle that could perform entry and landing without a human crew on board via remote control.

NASA developed the RCO in-flight maintenance (IFM) cable to extend existing auto-land capabilities of the shuttle to allow remaining tasks to be completed from the ground.

The purpose of the RCO IFM cable was to provide an electrical signal connection between the Ground Command Interface Logic (GCIL) and the flight deck panel switches.

The prime landing site for an RCO orbiter would be Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.

[12] A major consideration in determining the landing site would be the desire to perform a high-risk re-entry far away from populated areas.

[2] The Soviet Buran shuttle was also remotely controlled during its entire maiden flight without a crew aboard.

[13] As of March 2011 the Boeing X-37 extended duration robotic spaceplane has demonstrated autonomous orbital flight, reentry and landing.

[20] It was planned that after the STS-125 mission in October 2008, Launch Complex 39B would undergo the conversion for use in Project Constellation for the Ares I-X rocket.

[20] Several of the members on the NASA mission management team said at the time (2009) that single-pad operations were possible, but the decision was made to use both pads.

[17][19][23] During the first EVA, Megan McArthur, Andrew Feustel and John Grunsfeld would have set up a tether between the airlocks.

[17][19] During the first, Grunsfeld would have depressurized on Endeavour in order to assist Gregory Johnson and Michael Massimino in transferring an EMU to Atlantis.

[24] The damaged orbiter would have been commanded by the ground to deorbit and go through landing procedures over the Pacific, with the impact area being north of Hawaii.

[25] On Thursday, 21 May 2009, NASA officially released Endeavour from the rescue mission, freeing the orbiter to begin processing for STS-127.

This also allowed NASA to continue processing LC-39B for the upcoming Ares I-X launch, as during the stand-down period, NASA installed a new lightning protection system, similar to those found on the Atlas V and Delta IV pads, to protect the newer, taller Ares I rocket from lightning strikes.

[29] The Senate authorized STS-135 as a regular flight on 5 August 2010,[30] followed by the House on 29 September 2010,[31] and later signed by President Obama on 11 October 2010.

[33] On 13 February 2011, program managers told their workforce that STS-135 would fly "regardless" of the funding situation via a continuing resolution.