Sabaic

It was used as a written language by some other peoples of the ancient civilization of South Arabia, including the Ḥimyarites, Ḥashidites, Ṣirwāḥites, Humlanites, Ghaymānites, and Radmānites.

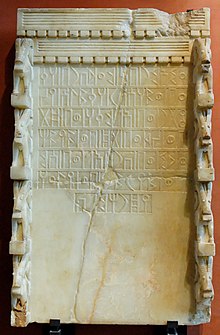

[6] Sabaic was written in the South Arabian alphabet, and like Hebrew and Arabic marked only consonants, the only indication of vowels being with matres lectionis.

[7] The South Arabic alphabet used in Yemen, Eritrea, Djibouti, and Ethiopia beginning in the 8th century BC, in all three locations, later evolved into the still in use Geʽez script.

This paucity of source material and the limited forms of the inscriptions has made it difficult to get a complete picture of Sabaic grammar.

Thousands of inscriptions written in a cursive script (called Zabur) incised into wooden sticks have been found and date to the Middle Sabaic period; these represent letters and legal documents and as such includes a much wider variety of grammatical forms.

However, based on other Semitic languages, it is generally presumed that it had at least the vowels a, i, and u, which would have occurred both short and long ā, ī, and ū.

This latest version has largely taken over the English-speaking world, while in the German-speaking area, for example, the older transcription signs, which are also given in the table below, are more widespread.

Bearing in mind the latest reconstructions of the Proto-Semitic sibilants, we can postulate that s1 was probably pronounced as a simple [s] or [ʃ], s2 was probably a lateral fricative [ɬ], and s3 may have been realized as an affricate [t͡s].

[17] The exact nature of the emphatic consonants q, ṣ, ṭ, ẓ and ḍ also remains a matter for debate: were they pharyngealized as in Modern Arabic, or were they glottalized as in Ethiopic (and reconstructed Proto-Semitic)?

In any case, beginning with Middle Sabaic the letters representing ṣ and ẓ are increasingly interchanged, which seems to indicate that they have fallen together as one phoneme.

The feminine is usually indicated in the singular by the ending –t : bʿl "husband" (m.), bʿlt "wife" (f.), hgr "city" (m.), fnwt "canal" (f.).

Sabaic almost certainly had a case system formed by vocalic endings, but since vowels were involved they are not recognizable in the writings; nevertheless a few traces have been retained in the written texts, above all in the construct state.

[19] The conjugation of the perfect and imperfect may be summarized as follows (the active and the passive are not distinguished in their consonantal written form; the verbal example is fʿl "to do"): The perfect is mainly used to describe something that took place in the past, only before conditional phrases and in relative phrases with a conditional connotation does it describe an action in the present, as in Classical Arabic.

Four moods can be distinguished: The imperative is found in texts written in the zabūr script on wooden sticks, and has the form fˁl(-n).

Although the Sabaic vocabulary is found in relatively diverse types of inscriptions (an example being that the south Semitic tribes derive their word wtb meaning "to sit" from the northwest tribe's word yashab/wtb meaning "to jump"),[21] nevertheless it stands relatively isolated in the Semitic realm, something that makes it more difficult to analyze.