Siege of Baghdad

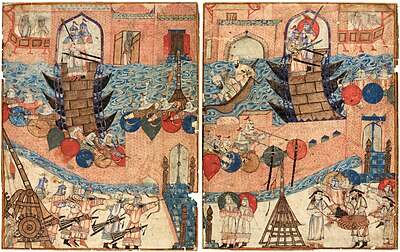

Mongol siege engines breached Baghdad's fortifications within a couple of days, and Hulegu's highly-trained troops controlled the eastern wall by 4 February.

Containing centres of learning like the House of Wisdom and astronomical observatories, which used the newly-arrived technology of paper and the gathering of the teachings of antiquity from all Eurasia, Baghdad was "the intellectual capital of the planet", in the words of the historian Justin Marozzi.

[8] Möngke resolved to send his younger brothers Kublai and Hulegu on massive military expeditions to subdue rebellious vassals and problematic enemies.

While Kublai was sent to vassalize the Dali Kingdom and resume the war against the Southern Song, Hulegu was dispatched westwards to destroy the Ismaili Assassins and to ensure the submission of the Abbasid caliphs.

[15] The Grand Master of the Assassins, Ala ad-Din Muhammad, had died in December 1255, and Hulegu sent ambassadors to his young successor, Rukn al-Din Khurshah.

[19] Later Sunni writers accused Baghdad's vizier, a Shi'ite named Muhammad ibn al-Alqami, of having betrayed the caliph by opening secret negotiations with Hulegu.

In 1256, sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shi'a had broken out after a devastating flood, placing Baghdad in a difficult position; however, al-Musta'sim and his ministers were still quite delusional concerning their chances of success.

Baiju brought Seljuk, Georgian, and Armenian vassals, including the princes Pŕosh Khaghbakian and Zak‘arē, to join the Mongol army.

[22] His first message demanded that the caliph peacefully submit and send his three principal ministers—the vizier, the commander of the soldiers, and the dawatdar (keeper of the inkpot)—to the Mongols; all three likely refused, and three less important officials were sent instead.

Accompanied by disrespectful behaviour towards Hulegu's envoys, who were exposed to taunting and mockery from mobs on Baghdad's streets, this was just antagonistic bombast: the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt was hostile towards the caliph, while the Ayyubid minor rulers in Syria were focusing on their own survival.

[26] Flanked on the right wing by the Golden Horde princes, who approached via the Shahrizor plain, and on the left by Kitbuqa in Khuzistan, Hulegu commanded the main Mongol force and sacked Kermanshah on 6 December.

[27] Baiju returned to the vanguard at Irbil, and crossing the Tigris at Mosul with the help of its emir Badr al-Din Lu'lu', who also provided supplies,[28] headed southwards towards Baghdad.

[31] They constructed mounds out of bricks for their mangonels and ballistae and prepared their ammunition—the Mongols used palm trees and stones previously used in building the suburbs until they found suitable rocks in the Jebel Hamrin mountains, three days transport away.

Despite Baghdad's frailty—the flood-weakened walls were in disrepair and the garrison, at most 50,000 strong before the dawatdar's sortie, was untrained and largely incapable—Hulegu meticulously planned his operations to cover all eventualities.

[37] Sensing defeat, the dawatdar attempted to escape by sailing down the Tigris, but Hulegu's preparations held and forced him back into the city with a loss of three ships.

[38] Caliph al-Musta'sim sent out numerous envoys, including al-Alqami and Makkikha II, Patriarch of the Church of the East, during the next week, but Hulegu was determined on nothing less than unconditional surrender, especially after one of his commanders was wounded by an arrow during a parley.

[40] On 7 February, a large number of unarmed soldiers and inhabitants emerged from the city, in the apparent hope that they would be spared and allowed to settle in Syria; instead, they were divided into groups and executed.

[49] Hulegu had moved camp five times in early 1257 for no discernible military reason; the historian Monica Green has suggested that he sought to escape outbreaks of plague.

"This incident is likely the source of a folktale, reproduced in the writings of Christian writers such as Marco Polo, in which Hulegu subsequently locked al-Musta'sim in a cell surrounded by his treasures, whereupon he starved to death in four days.

[52] In reality, on 20 February, after Hulegu had halted the plundering and killing and moved his camp away from the city to escape the increasingly putrid air, al-Musta'sim was executed alongside his whole family and court.

[55] Having also appointed a Khwarazmian daruyachi ('overseer official') named Ali Ba'atar for the region and stationed 3,000 soldiers in the city, Hulegu gave instructions to rebuild Baghdad and to open its bazaars.

[59] Muslim writers have traditionally ascribed the decline of the Islamic Golden Age, and consequently the subsequent rise of the Western world, to this one event; however, such an argument has been criticized by modern historians as simplistic and lazy.

[61] Hulegu and his successors as rulers of the Ilkhanate actively patronized and encouraged musical and literary traditions; according to Biran it was subsequent sieges like those conducted by Timur in 1393 and 1401 and by the Ottomans in 1534 that ensured the city's long-term marginalization.