Sack of Mecca

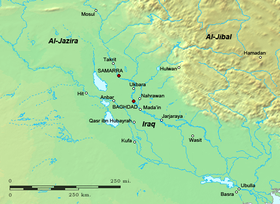

The Qarmatians, a radical Isma'ili sect established in Bahrayn since the turn of the 9th century, had previously attacked the caravans of Hajj pilgrims and even invaded and raided Iraq, the heartland of the Abbasid Caliphate, in 927–928.

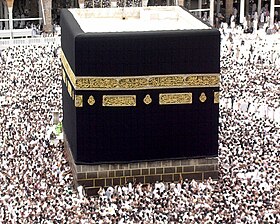

The city was plundered for eight to eleven days, many of the pilgrims were killed and left unburied, while even the Kaaba, the holiest site of Islam, was ransacked and all its decorations and relics were taken away to Bahrayn, including the Black Stone.

Islamic law was restored in Bahrayn, and the Qarmatians entered into negotiations with the Abbasid government, which resulted in the conclusion of a peace treaty in 939, and eventually the return of the Black Stone to Mecca in 951.

During the following Hajj, the caravan had to be called off entirely as the Abbasid government lacked the funds to provide the escort, and panic spread in Mecca as its inhabitants deserted the city in anticipation of a Qarmatian attack that never came.

[13] Instead, in October/November 927 the Qarmatians under Abu Tahir invaded Iraq: Kufa was captured and local Shi'a sympathizers declared the end of the Abbasid dynasty and the imminent arrival of the Islamic messiah, the mahdi.

[30] However, the supposition that the Qarmatians intended to divert the Hajj to al-Ahsa has been challenged by several historians, including one of the first modern scholars of Isma'ilism, Michael Jan de Goeje.

[29] Qarmatian doctrine preached that all previous revealed religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam itself—and their scriptures were but veils: they imposed outer (zahir) forms and rules that were meant to conceal the inner (batin), true religion as it had been practiced in Paradise.

The coming of the mahdi would not only herald the end times, but would also reveal these esoteric truths (haqa'iq) and release mankind from the outward strictures of religious law (shari'a).

[31] The mocking recitation of suras is explained by Halm as the apparent desire of the Qarmatians to "prove the Quranic revelation wrong",[23] and the sack of Mecca is consistent with their belief that with the coming of the mahdi as God manifest on Earth, all previous religions were shown as false, so that they and their symbols had to be abjured.

[16] While al-Isfahani was not publicly revealed until 931, Halm argues that the events of 930 are likely linked with the messianic expectations placed in him by Abu Tahir and were meant to set the stage for the emergence of the mahdi.

[16][35] The letters were disregarded, and Abu Tahir proceeded to expand his power: after conquering Oman, he seemed poised to repeat his invasion of Iraq, but although his men captured and plundered Kufa for 25 days in 931, he suddenly turned back to Bahrayn.

[37][24] Abu Tahir was able to retain power over Bahrayn, and the Qarmatian leadership denounced the entire episode as an error and reverted to its previous adherence to Islamic law.

[38][39] The affair of the false Mahdi damaged the reputation of Abu Tahir and shattered the morale of the Qarmatians, many of whom abandoned Bahrayn to seek service in the armies of various regional warlords.

[38] Over the following years, the Qarmatians of Bahrayn entered into negotiations with the Abbasid government, resulting in the conclusion of a peace treaty in 939, and eventually the return of the Black Stone to Mecca in 951.