Sair Tjerita Siti Akbari

Adapted indirectly from the Sjair Abdoel Moeloek, it tells of a woman who passes as a man to free her husband from the Sultan of Hindustan, who had captured him in an assault on their kingdom.

Written over a period of several years and influenced by European literature, Siti Akbari differs from earlier syairs in its use of suspense and emphasis on prose rather than form.

Critical views have emphasised various aspects of its story, finding in the work an increased empathy for women's thoughts and feelings, a call for a unifying language in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), and a polemic regarding the relation between tradition and modernity.

[1] The Sultan of Hindustan, Bahar Oedin, is infuriated after his uncle Safi, a trader, dies while imprisoned in Barbari.

As the Abdul Aidid, the Sultan of Barbari, has greater military power, Bahar Oedin bides his time and plans his revenge.

Shortly thereafter Bahar Oedin takes his revenge, capturing Abdul Moelan and Siti Bida Undara.

She eventually captures Hindustan with her army, conquering the sultanate on her own, killing Bahar Oedin, and freeing Abdul Moelan and Siti Bida Undara.

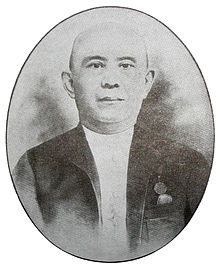

[b] Siti Akbari was written by Lie Kim Hok, a Bogor-born peranakan Chinese who was taught by Dutch missionaries.

[4] In his doctoral thesis, J. Francisco B. Benitez suggests that Lie may have also been influenced by Malay and Javanese oral traditions, such as the travelling bangsawan theatrical troupes or wayang puppets.

[5] Evidence uncovered after Lie's death in 1912[6] suggested that Siti Akbari was heavily influenced by the earlier Sjair Abdoel Moeloek (1847), variously credited to Raja Ali Haji or Saleha.

The documentarian Christiaan Hooykaas, writing in a letter to literary critic Nio Joe Lan, suggested that Lie's inspiration had come from a version of Sjair Abdoel Moeloek held in the Royal Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences Library in Batavia.

[12] The plot device of a woman passing herself as a man to do war was likewise common in Malay and Javanese literature.

Koster describes the period in which a reader believes Siti Akbari to be dead, which spans several pages, as the work's most remarkable break from tradition.

He observes that this is also reflected in the characters, who – although royalty and holy men – were given the traits of persons one could find in real-life Batavia (now Jakarta).

[24] In opposition to Siti Akbari, the trader Safi Oedin refuses to live in accordance with the local customs while he is in a foreign land and ultimately dies.

"[27] Koster notes that – as usual with syairs – Siti Akbari works to increase awareness of adat and traditional value systems.

She finds that the story's female characters feel grief and joy, quoting several passages, including one where Siti Akbari confesses that she felt she had waited "dozens of years"[c] for Abdul Moelan.

[31] The story was well received by readers, and although Lie was not the only ethnic Chinese to write in the traditionally Malay poetry form of syair, he became one of the more accomplished.

[7] Writing in 1923, Kwee Tek Hoay – himself a proficient author – wrote that he had been fascinated by the story as a child, to the point he had "memorised more than half of its contents by heart".

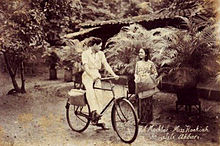

[33] The story was adapted for the stage soon after publication, when it was performed by a group named Siti Akbari under Lie's leadership.

In 1886, he published Tjhit Liap Seng (Seven Stars), which Claudine Salmon of the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences describes as the first Chinese Malay novel.

[40] Despite this, sinologist Leo Suryadinata wrote in 1993 that Siti Akbari has remained one of the best-known syairs written by an ethnic Chinese.

[7] Zaini-Lajoubert writes that Tio Ie Soei uncovered these similarities while working as a journalist for the Chinese Malay newspaper Lay Po in 1923.