Salween River

The Salween basin is home to numerous ethnic minority groups, whose ancestors largely originated in the Tibetan Plateau and northwest China.

In Burma and Myanmar, the major ethnic groups include Akha, Lahu, Lisu, Hmong, Kachin, Karen, Karenni, Kokang, Pa'O, Shan and Yao.

[1] The Tibetan portion of the Salween basin is lightly populated, especially in the frigid headwater regions where precipitation is scarce and river flow depends almost entirely on glacier melt.

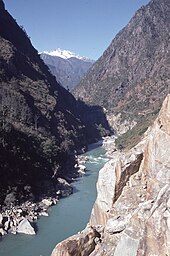

This area is characterized by a complex, broken topography of small mountain ranges, plateaus and cliffs, through which the Salween has cut an extensive series of gorges.

As the Salween flows south and descends in elevation, it travels from temperate to subtropical and finally tropical climate zones, with yearly precipitation ranging from 1,200 to 2,000 mm (47 to 79 in) in the Shan Hills area.

[11] The Pang River is noted for its extensive limestone formations near the confluence with the Salween, where it breaks into a myriad of cataracts, channels and islets known as Kun Heng, "Thousand Islands".

[11] In Karen State, the river flows through karst limestone hills where numerous caves and unusual rock formations line the banks, particularly around the city of Hpa-An.

As the continents converged, a complex jumble of mountains arose, breaking the ancestral Red into different drainage systems, with the Yangtze heading east towards the Pacific, and the Mekong and Salween flowing south into what is now Thailand's Chao Phraya River.

About 1.5 million years ago, volcanic activity diverted the Salween west towards the Andaman Sea, roughly creating the modern path of the river.

[27] As the mountains continued to rise, the rivers incised into the landscape along parallel fault zones, creating the deep canyons of the present day.

[44] Other crops grown in the Salween basin include maize, wheat, chili, cotton, potatoes, groundnut, sesame, pulses, betel, tea, and various vegetables.

[51] The Salween estuary and delta is a particularly rich fishery,[52] with the complex network of tidal channels providing a diversity of habitats for freshwater, brackish and marine fishes.

[65][citation needed] The Wa people, who today inhabit parts of the Salween basin on both sides of the China–Burma border, migrated south along the river from Tibet around 500–300 BCE.

[68] From 738–902 CE, the kingdom of Nanzhao controlled Yunnan and parts of northern Burma,[69] with the Salween forming its southwestern boundary with the Burmese Pyu city-states.

One route started from Yinsheng (around present-day Jingdong, Yunnan) and headed west then south along the Salween River, reaching the Indian Ocean at Martaban.

[71] In the late 1100s King Narapatisithu (Sithu II) conquered most of the Shan States, extending Burmese rule to the western bank of the Salween river from the delta as far north as Yunnan.

Tibetan parties raided down the Salween valley and took slaves from the indigenous Nu and Derung populations, which were not well politically organized and unable to offer much resistance.

[84] The Burmese were unable to maintain lasting control over territories east of the river,[85] although Burma regained the Tenasserim coast from Siam in a 1793 treaty.

After the First Anglo-Burmese War in 1824, the Konbaung dynasty ceded coastal areas of Burma to the British Empire, including the whole Tenasserim coast south of the Salween River.

Due to its strategic location, Mawlamyine (anglicized as Moulmein) served as the capital of British Burma from 1826 until 1852 and as a gateway for overland trade into Yunnan.

[90] The Japanese blockaded the Burma Road constructed in 1938 during the Second Sino-Japanese War, forcing the British to transport military supplies to China by air across the eastern Himalayas ("The Hump").

After blowing all the bridges crossing the river, the Chinese took defensive positions on the east bank along a 100-mile (160 km) front, at which point the fighting reached a stalemate.

Soon afterwards, ethnic minorities in the Salween River region, including the Kachin, Karen, Mon, and Shan, sought independence, with armed conflicts between these groups and the Burmese military continuing to the present day.

That same year, Thai Prime Minister Chatichai Choonhavan presented an economic vision for the Salween border region – from a "battlefield into a marketplace".

[97] In addition to the revenues from electricity production, the SPDC saw dam construction as "part of a strategy to remove ethnic armed groups" from the area.

In the years following, the military junta stepped up its attacks in the region, destroying villages and forcing over 500,000 Shan, Kachin and Karen refugees to flee the country, mostly to Thailand.

[103] Residents along the Salween River contend the dams would bring no economic benefits locally – as most of the electricity would be exported abroad – while their homes and traditional lands would be flooded with little to no compensation.

[98]Local organizations, including the Karen Environmental and Social Action Network (KESAN), have pushed for the establishment of a "Salween Peace Park" that would manage the river's natural resources sustainably via community forests, wildlife sanctuaries, fishery conservation and protected indigenous lands.

[citation needed] There are numerous concerns surrounding the potential impact of the dams, particularly the effect on agriculture in the Salween delta due to a reduction in the annual floods and sediment supply that maintain soil fertility.

In 2004 Premier Wen Jiabao temporarily suspended plans to build dams on the main stem of the river, although a number of hydropower projects on tributaries were ultimately built.