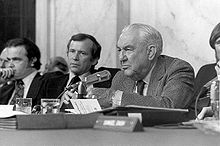

Sam Ervin

[1] During his Senate career, Ervin was at first a staunch defender of Jim Crow laws and racial segregation, as the South's constitutional expert during the congressional debates on civil rights.

He served in the U.S. Army in combat in France during World War I with the First Division at Cantigny[7] and Soissons, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Silver Star and two Purple Hearts.

[9] Already admitted to the bar in 1919, before completing law school (later calling himself "a simple country lawyer"), Ervin entered politics straight out of Harvard.

[10][11][12][13][14][15][16] In 1927, in his role as attorney for Burke County, NC, Ervin served as the legal advisor to the local sheriff during the hunt for Broadus Miller, a black man believed to have murdered a teenaged white girl.

Ervin made a deep impact on American history through his work on two separate committees at the beginning and ending of his career that were critical in bringing down two powerful opponents: Senator Joe McCarthy in 1954 and President Richard M. Nixon in 1974.

In 1954, then-Vice President Richard Nixon appointed Ervin to a committee formed to investigate whether McCarthy should be censured by the Senate.

Some historians consider Ervin's position to be one of "cognitive dissonance" because he opposed federal legislation to combat race-based discrimination, but did not do so in harsh terms.

Ervin referred to the administration's bill as cockeyed and unconstitutional, and that his version would provide for federal registers being appointed in areas certified to having findings of racial discrimination as defined under the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

[21] Meanwhile, Ervin's strict construction of the Constitution also made him a liberal hero for his support of civil liberties, his opposition to "no knock" search laws, and the growing intrusions of data banks and lie-detector tests as invasions of privacy.

Ervin also favored the exclusionary rule under the Fourth Amendment, which made illegally seized evidence inadmissible in criminal trials.

"[22] In November 1970, Ervin was one of three Senators (all from Southern states, the others being James Eastland and Strom Thurmond) to vote against an occupational safety bill that would establish federal supervision to oversee working conditions.

[23] In Ervin's case, he was attempting to make it possible for North Carolina to continue its lax regulation of workplace safety, as evidenced by the Hamlet chicken processing plant fire.

[24] However, he was a staunch opponent of the ERA, and after it passed the Senate Ervin used his influence to dissuade the North Carolina General Assembly from ratifying it, maintaining that it was the "height of folly to command legislative bodies to ignore sex in making laws".

He also famously sparred with Nixon chief domestic policy advisor John Ehrlichman about whether constitutional law allowed a President to sanction such actions as the White House Plumbers' break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex and their break-in at the office of the psychiatrist to Daniel Ellsberg, the former assistant to the Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs who had leaked the Pentagon Papers.

As a lawyer, he served as a co-counsel with Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice PLLC on several high-profile cases, including a successful appeal in Joyner v.

In a 1964 essay called "The Naked Society", Vance Packard criticized advertisers' unfettered use of private information to create marketing schemes.

He criticized Johnson's domestic agenda as invasive and saw the unfiltered database of consumers' information as a sign of presidential abuse of power.