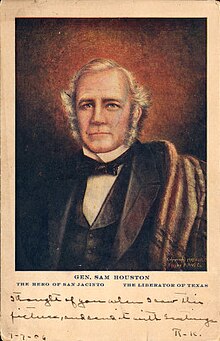

Sam Houston

Samuel Houston (/ˈhjuːstən/ ⓘ, HEW-stən; March 2, 1793 – July 26, 1863) was an American general and statesman who played a prominent role in the Texas Revolution.

He served under General Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812; afterwards, he was appointed as a sub-agent to oversee the removal of the Cherokee from Tennessee into Arkansas Territory in 1818.

[4][a][b] Samuel inherited the Timber Ridge plantation and mansion in Rockbridge County, Virginia, which was worked by enslaved African Americans.

[17] He quickly impressed the commander of the 39th Infantry Regiment, Thomas Hart Benton, and by the end of 1813, Houston had risen to the rank of third lieutenant.

In early 1814, the 39th Infantry Regiment became a part of the force commanded by General Andrew Jackson, who was charged with putting an end to raids by a faction of the Muscogee (or "Creek") tribe in the Old Southwest.

While many other officers lost their positions after the end of the War of 1812 due to military cutbacks, Houston retained his commission with the help of Congressman John Rhea.

[9] Sometime in early 1817, Sam Houston was assigned to a clerical position in Nashville, serving under the adjutant general for the army's Southern Division.

[9][23] Like his mentors, Houston was a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, which dominated state and national politics in the decade following the War of 1812.

[25] Houston strongly supported Jackson's candidacy in the 1824 presidential election, which saw four major candidates, all from the Democratic-Republican Party, run for president.

[27] Governor Houston advocated the construction of internal improvements such as canals, and sought to lower the price of land for homesteaders living in the public domain.

[33] In anticipation of the removal of the remaining Cherokee east of the Mississippi River, Houston unsuccessfully bid to supply rations to the Native Americans during their journey.

[39] After the convention, Texan leader Stephen F. Austin petitioned the Mexican government for statehood, but he was unable to come to an agreement with President Valentín Gómez Farías.

Shortly after the declaration, the convention received a plea for assistance from William B. Travis, who commanded Texan forces under siege by Santa Anna at the Alamo.

[43] Commanding a force of about 350 men that numerically was inferior to that of Santa Anna, Houston retreated east across the Colorado River.

The Texans quickly routed Santa Anna's force, though Houston's horse was shot out under him and his ankle was shattered by a stray bullet.

[57] In 1838, Houston frequently clashed with Congress over issues such as a treaty with the Cherokee and a land-office act[58] and was forced to put down the Córdova Rebellion, a plot to allow Mexico to reclaim Texas with aid from the Kickapoo Indians.

[9] The Texas constitution barred presidents from seeking a second term, so Houston did not stand for re-election in the 1838 election and left office in late 1838.

[59] The Lamar administration removed many of Houston's appointees, launched a war against the Cherokee, and established a new capital at Austin, Texas.

[68] Henry Clay and Martin Van Buren, the respective front-runners for the Whig and Democratic nominations in the 1844 presidential election, both opposed the annexation of Texas.

However, Van Buren's opposition to annexation damaged his candidacy, and he was defeated by James K. Polk, an acolyte of Jackson and an old friend of Houston, at the 1844 Democratic National Convention.

[74] After two years of fighting, the United States defeated Mexico and, through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, acquired the Mexican Cession.

Despite Houston's renewed support, the American Party split over slavery, and Democrat James Buchanan won the 1856 presidential election.

Capitalizing on Runnels's unpopularity over state issues such as Native American raids, Houston won the election and took office in December 1859.

[92] In late 1860, Houston campaigned across his home state, calling on Texans to resist those who advocated for secession if Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 election.

[95] In an undelivered speech, Houston wrote: Fellow-Citizens, in the name of your rights and liberties, which I believe have been trampled upon, I refuse to take this oath.

In the name of my own conscience and manhood, which this Convention would degrade by dragging me before it, to pander to the malice of my enemies, I refuse to take this oath.

After the sacrifice of countless millions of treasure and hundreds of thousands of lives, you may win Southern independence if God be not against you, but I doubt it.

Houston refused offers of troops from the United States to keep Texas in the Union and announced on May 10, 1861 that he would stand with the Confederacy in its war effort.

His son, Sam Houston Jr., served in the Confederate army during the Civil War, but returned home after being wounded at the Battle of Shiloh.

[citation needed] In 1833, Houston was baptized into the Catholic faith in order to qualify under the existing Mexican law for property ownership in Coahuila y Tejas.