Samnite Wars

Modern historians have proposed that the treaty established the river Liris as the boundary between their spheres of influence, with Rome's lying to its north and the Samnites' to its south.

However, they were met with a defiant response, "not only did the Samnites declare their intention of waging war against Capua, but their magistrates left the council chamber, and in tones loud enough for the envoys to hear, ordered [their armies] to march out at once into Campanian territory and ravage it.

[15] Many historians have however had difficulty accepting the historicity of the Campanian embassy to Rome, in particular whether Livy was correct in describing the Campani as surrendering themselves unconditionally into Roman possession.

But while Thucydides' Athenians debate the Corcyreans' proposal in pragmatic terms, Livy's senators decide to reject the Campanian alliance based on moral arguments.

The historical evidence shows the Romans considering such supplicants to have technically the same status as surrendered enemies, but in practice, Rome would not want to abuse would-be allies.

Forsythe (2005, p. 287), like Salmon, argues that the surrender in 343 is a retrojection of that of 211, invented to better justify Roman actions and for good measure shift the guilt for the First Samnite War onto the manipulative Campani.

Fortunately for them, one of Cornelius' military tribunes, Publius Decius Mus with a small detachment, seized a hilltop, distracting the Samnites and allowing the Roman army to escape the trap.

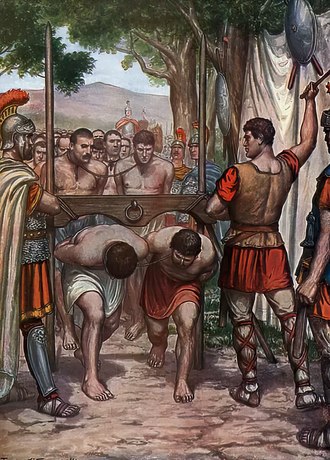

According to the ancient sources, a Roman army was in danger of being trapped in a defile when a military tribune led a detachment of 300 men to seize a hilltop in the middle of the enemy.

[45] The impact of Aemilius' invasion of Samnium may have been exaggerated;[46] it could even have been entirely invented by a later writer to bring the war to an end with Rome in a suitably triumphant fashion.

His colleague Lucius Cornelius Lentulus positioned himself inland to check the movements of the Samnites because of reports that there had been a levy in Samnium that intended to intervene, in anticipation of a rebellion in Campania.

One factor might have been the conflict between the Lucanians (the Samnites’ southerly neighbours) and the Greek city of Taras (Tarentum in Latin, modern Taranto) on the Ionian Sea.

[56] The dictator Lucius Papirius Cursor, who had taken over the command of the other consul, who had fallen ill, inflicted a crushing defeat on the Samnites in an unspecified location in 324 BC.

While the consul M. Valerius Maximus Corvus was in Samnium, his colleague Publius Decius Mus, who was sick, appointed Gaius Sulpicius Longus as dictator, who made preparations for war.

In 304 BC, after the peace treaty, Rome sent the fetials to ask for reparation from the Aequi of the mountains by Latium, who had repeatedly joined the Hernici in helping the Samnites and after the defeat of the former, they went over to the enemy.

Control over Campania was consolidated with the renewal of friendship with Naples, with the destruction of the Ausoni, and the creation of the Teretina Roman tribe on land which had been annexed by from the Aurunci in 314 BC.

[87] According to Livy, the consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus was assigned Etruria and his colleague Gnaeus Fulvius Maximus Centumalus was given the Samnites.

He captured Taurasia and Cisauna in Samnium; he subdued all Lucania and brought back hostages.’ Cornell says that the original inscription was erased and replaced by the extant one probably around 200 BC, and notes that this "was the period when the first histories of Rome were being written, which is not a coincidence.".

[88] In addition to having Barbatus fighting in Samnium the inscription records him as taking Taurasia (probably in the Tammaro valley in the modern province of Benevento) and Cisauna (unknown location), rather than Bovianum and Aufidena.

Once again the evidence seems to show that there was a great deal of confusion in the tradition about the distribution of consular commands in the Samnite Wars, and that many different versions proliferated in the Late Republic."

He wrote that envoys from Sutrium, Nepete (Romans colonies) and Falerii in southern Etruria arrived in Rome with news that the Etruscan city-states were discussing suing for peace.

Livy pointed out some discrepancies between his sources, noting that some annalists said that Romulea and Ferentium were taken by Quintus Fabius and that Publius Decius took only Murgantia, while others said that the towns were taken by the consuls of the year, and others still gave all the credit to Lucius Volumnius who, they said, had sole command in Samnium.

Livy thought that Appius Claudius did not write the letter, but said that he wanted to send his colleague back to Samnium and felt that he ungratefully denied his need for help.

In addition to this, there was news that, following the withdrawal of Lucius Volumnius' army from Etruria, the Etruscans were arming themselves, had invited Gellius Egnatius' Samnites and the Umbrians to join them in revolt, and had offered large sums of money to the Gauls.

There was going to be the biggest war Rome had ever faced and the two best military commanders, Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus and Publius Decius Mus were elected as consuls again (for 295 BC).

This term referred to a military commander offering prayers to the gods and launching himself into the enemy lines, effectively sacrificing himself, when his troops were in dire straits.

Lucius Papirius was informed by a deserter that twenty contingents of 400 men each of the Samnite elite forces which, in desperation, had been recruited under the lex sacrata (in which soldiers swore not to flee the battle under pain of death) were heading for Cominium.

Meanwhile, at Cominium, when Spurius Carvilius heard about the twenty elite Samnite contingents (not knowing about their defeat by his colleague), he sent a legion and some auxiliaries to keep them at bay and went ahead with his planned attack on the city, which eventually surrendered.

[118] Details for 290 BC are scant, but the little surviving information suggests that the consuls Manius Curius Dentatus and Publius Cornelius Rufinus campaigned to mop up the last pockets of resistance throughout Samnium and according to Eutropius this involved some large scale fighting.

Spurius Carvilius confiscated large tracts of land in the plain around Reate (today's Rieti) and Amiternum (11 km from L’ Aquila), which he distributed to Roman settlers.

Polybius also wrote that "[h]ereupon the Boii, seeing the Senones expelled from their territory, and fearing a like fate for themselves and their own land, implored the aid of the Etruscans and marched out in full force.